Nasa's Robonaut 2 scrubs up for space surgery

- Published

Robonaut 2 was built and designed at Nasa's Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas

It won't panic in an emergency, its hands don't shake after too little sleep, it won't miss a family after months away from base - in fact it doesn't even need to breathe.

Nasa's Robonaut 2 has the makings of the perfect space surgeon.

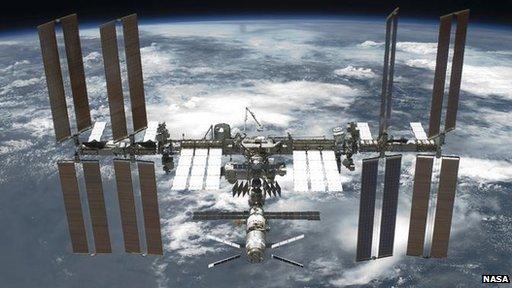

The humanoid has already been posted to the International Space Station, the only problem is its motor skills are somewhat rudimentary at the moment.

In truth, it can't even walk in zero gravity yet, and perhaps its most impressive physical feat to date has been to catch a floating roll of duct-tape.

But Nasa has high hopes for the new recruit, and techniques being developed by a team on the ground could mean the machine can eventually perform life-saving operations on its team-mates.

"The idea is for him to be the best medic, nurse, and physician," Dr Zsolt Garami of the Houston Methodist Hospital tells the BBC.

"Our plan is to use Robonaut as a telemedicine doctor in remote areas."

As Robonaut's name suggests, it is not alone. There are currently four versions of the android with more in development.

Initially R2 has been deployed using a fixed pedestal inside the ISS

One of them is being trained on Earth to find a pulse in a dummy's neck using ultrasound, then to stick a needle into a vein.

"You want to avoid hitting the carotid artery," Dr Garami says.

The robot has great potential for precise work, he says.

For example, once it can give an injection, it will be able to find the same spot on a human body and use the same angle for the needle again.

He sees the robot eventually being used to perform intricate medical operations like endovascular surgery, where a patient is operated on through their large blood vessels.

Robot cleaner

But in the short-term Robonaut 2 faces a more mundane role as the space station's cleaner

"The robot has to earn its stripes," Robonaut project leader Ron Diftler tells the BBC.

The machine has already been given "very boring tasks" on the International Space Station such as monitoring air flow from vents, he adds.

Robonaut 2 was shipped up to the space station as just a torso, head and arms.

The robot is capable of handling a wide variety of tools and machine interfaces

It is still waiting for a pair of legs to arrive on a forthcoming supply mission, but afterwards the robot should be able to begin to clean handrails, wipe down interior surfaces and other basic jobs.

The next stage is for it to learn to walk in, then to go outside the station to do maintenance tasks.

Its legs will have seven joints and cameras in the feet, so it will be able to "see" where it is going.

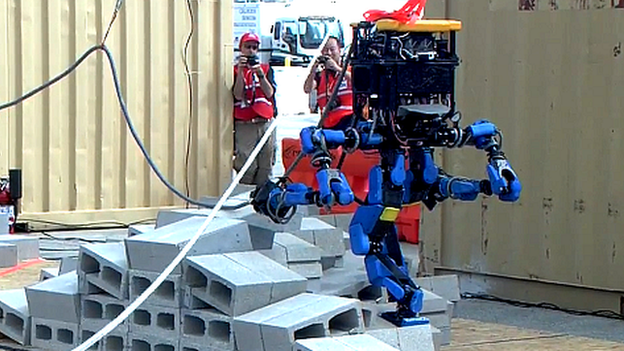

Eventually, the robot will perform "dull, dirty, and dangerous" jobs in inhospitable places, Mr Diftler says.

Robot control

Robonaut 2 can be remotely controlled by a ground crew member using a virtual-reality face mask and gloves.

The machine can be controlled from earth by a team who can see video sent from its cameras

The human controller can see what the robot sees, and manoeuvre it using gestures.

Hand and neck position data from the virtual reality kit are transmitted from the Houston command centre into space, and a video feed and data are beamed back.

It can also be controlled through keyboard commands on a laptop.

The robot has five eyes as part of its vision system, and can "see" the same wavelengths of light as a human, plus infrared light.

It has two high-resolution visible light cameras that transmit stereoscopic video to its operators, and two back-up cameras. It's "mouth" is actually an infrared camera to aid its depth perception.

There is no room in its head for a brain, so the aluminium and steel robot "thinks" with its stomach, which is packed with powerful processors.

The fingers have tendons that run into the forearm of the robot in a similar way to the human arm.

The robot should be able to take over simple. repetitive tasks on the space station

When the robot touches an object, tiny sensors on the fingers measure the force the robot is applying, and allow for a soft touch.

Robonaut 2 has not been designed to have super-human strength, but it's strong by human standards - it can lift and move a 20lb (9kg) weight around in Earth's gravity with one arm.

Time lag

One of the main challenges in surgical telemedicine is the time lag between the surgeon's movements and what the robot does, according to telepresence expert Gordon Mair from the University of Strathclyde.

A robonaut has already been fitted with legs at a lab in Houston

"If you were to make an incision, there would be a certain amount of time before the robot did it," he explains.

This could seriously affect an operation, as even a second's delay could mean the robot makes too deep or shallow an incision.

The signal takes time to transmit over long distances, with the time lag becoming longer as the distances get bigger.

The time lag for signals between Earth and the International Space Station can be up to a couple of seconds, and can cut out for much longer periods, Mr Diftler adds.

For missions to Mars, the lag could be 20 or 30 seconds, making the problem worse.

One possible way around the issue would be for astronauts inside the station to control the robot.

It could offer them an extra pair of hands, for example helping apply pressure on a wound during an operation.

The robot could also be programmed to act autonomously during parts of an operation, with a controller commanding it to go through a sequence of stages.

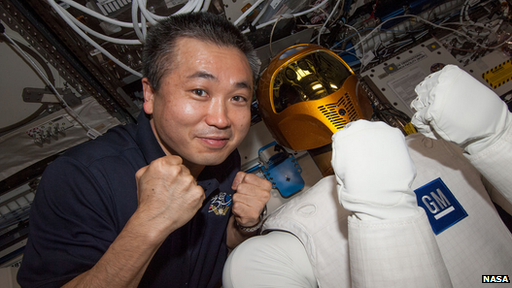

Japan's Koichi Wakata could not resist posing for a photo with Robonaut 2 in the ISS

Robonaut 2 already has some capabilities to act by itself in various tasks.

For example, Mission Control can tell it to pick something up, and it can use its vision system to locate the object, identify it, then reach out and grab it.

The automaton has a long road ahead of it before it can become an autonomous surgeon, but Nasa's big plans may see the robot go from space station toddler to medic on Mars.

- Published23 December 2013

- Published16 September 2013

- Published30 September 2013