Heartbleed bug denial by NSA and White House

- Published

Minecraft-maker Mojang shut down game servers while vulnerable software was patched

The US National Security Agency has denied it knew about or exploited the Heartbleed online security flaw.

The denial came after a Bloomberg News, external report alleging the NSA used the flaw in OpenSSL to harvest data.

OpenSSL is online-data scrambling software used to protect data such as passwords sent online.

Last year, NSA leaker Edward Snowden claimed the organisation deliberately introduced vulnerabilities to security software.

The bug, which allows hackers to snatch chunks of data from systems protected by OpenSSL, was revealed by researchers working for Google and a small Finnish security firm, Codenomicon, earlier this month.

OpenSSL is used by roughly two-thirds of all websites and the glitch existed for more than two years, making it one of the most serious internet security flaws to be uncovered in years.

"[The] NSA was not aware of the recently identified vulnerability in OpenSSL, the so-called Heartbleed vulnerability, until it was made public in a private-sector cyber security report," NSA spokeswoman Vanee Vines said in an email, adding that "reports that say otherwise are wrong."

A White House official also denied the US government was aware of the bug.

"Reports that NSA or any other part of the government were aware of the so-called Heartbleed vulnerability before April 2014 are wrong," White House national security spokeswoman Caitlin Hayden said in a statement.

"This administration takes seriously its responsibility to help maintain an open, interoperable, secure and reliable internet," she insisted, adding: "If the federal government, including the intelligence community, had discovered this vulnerability prior to last week, it would have been disclosed to the community responsible for OpenSSL."

Bloomberg, citing two people it said were familiar with the matter, said the NSA secretly made Heartbleed part of its "arsenal", to obtain passwords and other data.

It claimed the agency has more than 1,000 experts devoted to finding such flaws - who found the Heartbleed glitch shortly after its introduction.

The claim has unsettled many.

"If the NSA really knew about Heartbleed, they have some *serious* explaining to do," cryptographer Matthew Green said on Twitter.

The agency was already in the spotlight after months of revelations about its huge data-gathering capabilities.

Documents leaked by former NSA contractor Edward Snowden indicated the organisation was routinely collecting vast amounts of phone and internet data, together with partner intelligence agencies abroad.

President Barack Obama has ordered reforms that would halt government bulk collection of US telephone records, but critics argue this does not go far enough.

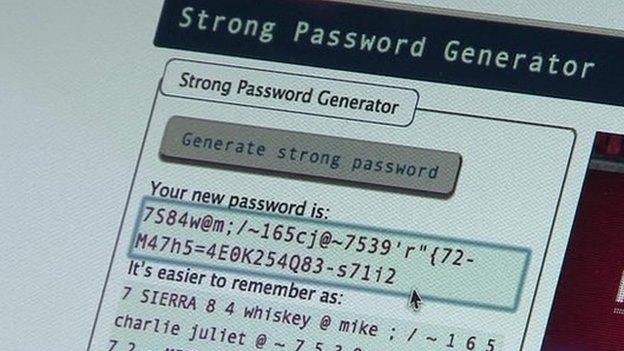

The US government said users should change passwords to patched services

Separate to its denials regarding the NSA, the US government also said it believes hackers are trying to make use of the flaw.

The Department of Homeland Security advised the public to change passwords, external for sites affected by the flaw, once they had confirmed they were secure, although it added that so far no successful attacks had been reported.

Several makers of internet hardware and software also revealed some of their products were affected, including network routers and switches, video conferencing equipment, phone call software, firewalls and applications that let workers remotely access company data.

The US government also said that it was working with other organisations "to determine the potential vulnerabilities to computer systems that control essential systems - like critical infrastructure, user-facing and financial systems".

The bug makes it possible for a knowledgeable hacker to impersonate services and users, and potentially eavesdrop on the data communications between them.

It only exposes 64K of data at a time, but a malicious party could theoretically make repeated grabs until they had the information they wanted. Crucially, an attack would not leave a trace, making it impossible to be sure whether hackers had taken advantage of it.

- Published11 April 2014

- Published10 April 2014

- Published10 April 2014

- Published10 April 2014

- Published10 April 2014

- Published9 April 2014

- Published8 April 2014