How to hack and crack the connected home

- Published

A suburban house has been transformed to help specialists find security flaws in smart devices and stop hackers taking control.

There are intruders in your home, ones that came with claims that they would make your life easier, that they could take over some of the drudgery so you could pursue some of life's finer pleasures.

What they did not mention was that they would let strangers look around your home and spill your secrets to anyone who asks the right questions.

These are not people letting you down, they are smart gadgets that will form what is known as the Internet of Things. All of them are a security disaster waiting to happen, suggests a BBC experiment.

The Internet of Things (IoT) stands in contrast to The Internet of People we currently enjoy and which lets us communicate and connect via a myriad of different technologies. The IoT promises to let stuff, devices and gadgets connect in the same way to both other hardware and us.

Via the IoT, those gadgets will tell us how they feel and we will control them via the same routes. Already it is possible to get smart thermostats, fridges, ovens, washing machines, air conditioners, lights, plugs, music players, baby monitors and many more.

Smart gadgets are better than dumb ones, say enthusiasts, because the ability to control them remotely will help us cope with the uncertainties of modern life.

With a net-connected oven, it will be possible to ensure your casserole is cooked to perfection as you arrive home hours late rather than dried up and cold because there was no way to communicate with the oven and adjust its timer.

The BBC's experiment brought together seven computer security experts who have been looking into so-called smart gadgets to find out how many they could subvert.

And how many could they crack the security on?

All of them.

"With most of them, if you can connect to it you can own it," said James Lyne, head of security research at Sophos.

Holey home

The BBC set up a house filled with a variety of smart gadgets and asked researchers to demonstrate how easy it was to crack the security systems on them.

Liam Hagan, a researcher from security firm Nettitude, said he was "shocked" at the poor job baby monitors and wi-fi cameras did to protect the pictures and sounds they were gathering.

"One of the big issues is that one wi-fi video camera makes itself available to the internet regardless of your firewall," he said. "Anyone who knows your IP address would be greeted with the login screen for the camera."

With one camera he tested, entering a default login name and password granted access to the images and sounds the device was capturing. There was no prompt to change these credentials to protect privacy, he said.

The days of dumb gadgets that cannot connect to the net could be numbered

Statistics gathered via the Shodan search engine, which catalogues devices and industrial equipment attached to the net, suggests there are more than 120,000 of just this one poorly protected gadget online already.

It was hard to know how many were giving strangers a look into homes up and down the country, he said, as there was no legal and ethical way to probe them.

The vulnerabilities in the device emerge from the very basic web server software it uses to post images online. That insecure software is currently being used by more than five million gadgets that are also already online.

More worryingly, he said, one wi-fi camera he tested had what is known as a "cross site scripting" vulnerability that lets an attacker inject their own code on to the device. This, said Mr Hagan, could be used to turn the video camera into a sniffer that could look for what else was on the network and let an attacker "pivot" to other more interesting systems such as PCs, smartphones and tablets.

Researchers from NCC Group managed to take control of several different devices including smart plugs that can be controlled via wi-fi, a wireless music system and a blu-ray DVD player.

Felix Ingram, from NCC Group, said vulnerabilities in a widely used networking system called UPnP helped his team take control of these devices.

UPnP was known to be vulnerable and kits already exist, one of which was written by an NCC Group researcher, that look for devices that use the networking protocol and try different vulnerabilities against them.

Many of the devices used UPnP to reach servers out on the wider net potentially exposing them to attackers. Built-in passwords that could not be changed made these ripe for exploitation, he said.

Gaining control of these devices was likely to annoy people more than anything else, said Mr Ingram, but other work by the company had exposed a more worrying aspect.

"The one that people really get concerned about is the microphone on a smart TV," he said. "We were able to bug a living room through it."

"That's when the internet of things starts to spook people out," he said. "when your stuff does more than you think it does or ever wanted it to."

Safety first

Mr Lyne from Sophos said, at the moment, the danger smart gadgets exposed people to was fairly small. However, he added, trends in computer crime suggest it might not stay that way.

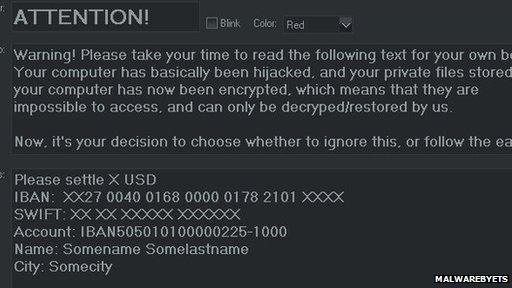

Cyber-thieves have started ransomware campaigns as it gets harder to attack PC operating systems

The work that Microsoft and other PC software vendors were doing to harden their code was already making dedicated cyber criminals look elsewhere for targets. This, he said, explained the rise in ransomware, technical support scams and attacks on computers at checkout points in shops.

The "ridiculously easy" way it was possible to subvert many smart gadgets was likely to make them a candidate for attack in the near future, he said. There had already been examples of attackers looking to subvert domestic hardware in a bid to grab online banking data.

Mr Lyne called on manufacturers to "step up" and do a better job of securing their products. In many cases, he said, there was no easy way to update the insecure firmware on these gadgets to fix the bugs researchers are finding. And, he added, many might be reluctant to apply them for fear of "bricking" the camera, washing machine or TV altogether.

He realised that there might be cost and usability implications for improving security but said it would not take much effort or cash to harden many products.

"There's a continuum between security and usability and it's true that the more you secure something there is a cost in how usable it is," he said. "At the moment, however, we are a long way off the wrong end of that scale."

Fixing many of the most obvious flaws on many devices would not hit usability at all, he said, because it would affect parts invisible to customers and users.

The BBC would like to thank Felix Ingram, Eleanor Chapman and George Hafiz from NCC Group, James Lyne from Sophos, and Rowland Johnson and Liam Hagan from Nettitude for their help with this story

- Published4 August 2014

- Published1 August 2014

- Published30 July 2014

- Published8 July 2014