Sega v Nintendo: Sonic, Mario and the 1990's console war

- Published

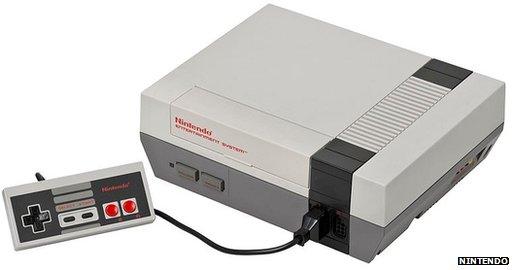

The battle between Nintendo and Sega in the 1990s arguably laid the foundation for the future of the video game industry in the United States.

It's the console war that arguably laid the foundations of the video games industry as we know it today.

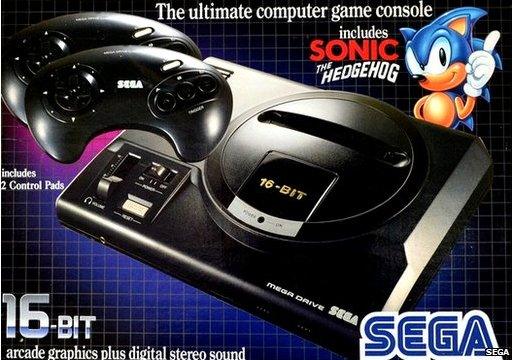

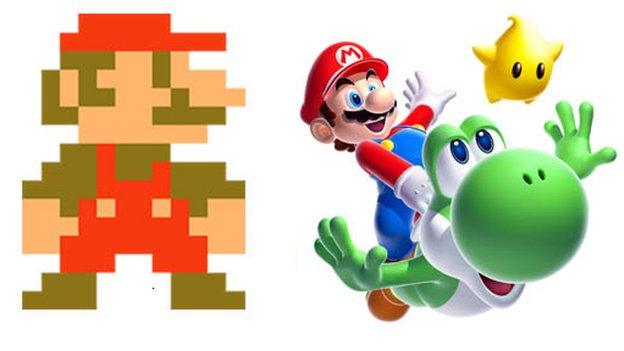

Sega's battle against Nintendo in the late-80s and early 90s is best known as the first clash between Sonic and Mario - the speedy hedgehog with attitude versus the plumber with the Mushroom Kingdom's most famous moustache.

But the skirmish also proved that Nintendo wasn't the only games firm capable of making money in North America after an earlier crash had wrecked Atari and others' prospects.

The contest also helped establish that console gaming wasn't just for kids.

Sega's console could be set to show blood in Mortal Kombat. which was not possible in the Nintendo version

Titles such as Mortal Kombat - featuring blood and gore on Sega's platform, and grey sweat on the more "family friendly" Super Nintendo Entertainment System - proved that targeting a more mature audience could be fruitful, as well as creating the need for gaming's first age ratings system.

"They made it relevant to an older demographic," concurs Ed Barton from the consultants Ovum.

"That was the start of a process that PlayStation later took one stage further, and if you look at the average age of a gamer in the UK is now in the mid-30s."

The forthcoming book - Console Wars: Sega, Nintendo, and the Battle that Defined a Generation - is a US-centric look at the affair based on interviews with executives from both firms.

Below are some of the stories at its core.

Sega's biggest battle may have been with itself

In 1990, Nintendo accounted for 90% of the US's $3bn (£1.8bn) video games sector.

Four years later, Sega had leapfrogged it thanks to the popularity of the Genesis - the US name for the Mega Drive - though this was a feat the company never replicated back home in Japan.

One of the constant themes of the book is that Sega of Japan (SoJ) never shared the scale of Sega of America (SoA)'s success, and repeatedly frustrated US chief executive Tom Kalinske's efforts.

"The leader at Sega Japan was Hayao Nakayama who was very smart but very harsh and he really drove the people there to be as successful as their counterparts in America," the book's author Blake Harris tells the BBC.

"I think that wore on them.

"Any time that you're looking across the ocean at someone who is in a similar position to you and is doing better, I imagine there would be seeds of jealousy."

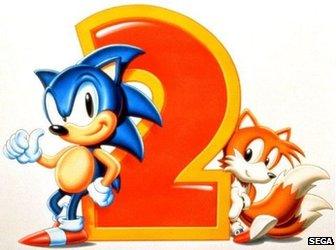

Tuesday 24 November 1992 was dubbed Sonic 2sday as part of a PR stunt organised by Sega's US team

He suggests this explains why Japan put the second Sonic title on sale days ahead of Sonic 2sday - an effort by the US squad to co-ordinate the globe's first synchronised launch of a video game.

Another, perhaps more important, struggle was over hardware.

Mr Kalinske first tried to team up with Sony to create a "Sega PlayStation", only to be told that Sega's engineers wanted to develop another console based on 2D sprite graphics rather than Sony's 3D polygon approach.

Next he attempted to link up with Silicon Graphics - the firm whose tech had been used to create the special effects in Jurassic Park and Terminator 2. But that too was rejected, allowing Nintendo to make use of one of the firm's chip in its Nintendo 64.

When the Genesis's successor, the Saturn, did launch it flopped in the US, not least because developers found it difficult to code for and Sony's machine was $100 cheaper.

"It's amazing that Sega and Sony had this opportunity to work together and take down Nintendo, but it ended up not working out" Mr Harris adds.

"And Sony ended up benefiting from that in the long run."

Nintendo was a "tortoise"

There's a phrase, coined by a Nintendo marketing executive, that is repeated several times in the book: "The name of the game is the game."

The idea is that the firm was obsessed by the quality of the titles released for its platform, leading it to impose restrictions on how many games other third-party publishers could release each year and reserving the right to reject their work if it felt it didn't meet Nintendo's standards.

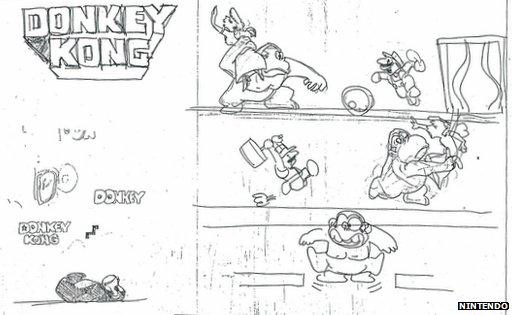

Donkey Kong Country helped extend sales of the SNES while the Nintendo 64 was being developed

Sega deliberately took the opposite tack, resulting in it being able to boast a larger games library, even if it had more duds.

"A central thesis of the book is the story of the tortoise and the hare," says Mr Harris.

"Sega came on the scene and were very flashy - they certainly put an emphasis on style.

"Nintendo was more focused on game play, game development and less so on marketing."

This strategy appeared to pay off when the release of Donkey Kong Country helped Nintendo regain its lead over Sega just before the end of 1994.

But Mr Harris notes that Nintendo's Wii U is now struggling against its brasher rivals, the PlayStation 4 and Xbox One.

Apple's Sculley influenced Sega

One curiosity unearthed by Mr Harris is how John Sculley - who was then Apple's chief executive - inadvertently intensified the console war.

The author recounts how Sega's US team wanted to pursue an aggressive marketing campaign involving negative TV ads and a shopping mall tour in which visitors would play both Sonic and Mario, and then pick their favourite.

SoA was worried Japan would block this because of the country's conservative approach to business.

But when the San Francisco-based office spoke to Mr Nakayama, it discovered he had just read about Mr Sculley's earlier time at Pepsi, and saw the benefits of the strategy.

Sega's campaign slogans were not subtle

"Nakayama was a very westernised Japanese business figure," says Mr Harris.

"Part of that influence was John Sculley, and the reverence [Nakayama] had for the Cola battles of the 80s and what Pepsi had done by going head to head against Coca-Cola.

"So, he allowed Tom Kalinsky in America to do those sorts of things, which the rest of the company and his board of directors maybe didn't agree with."

The no-holds-barred Genesis Does What Nintendon't campaign soon followed.

Sonic and Mario

Sonic and Mario may have personified the console war, but it could have been very different.

The hedgehog's Japanese developers originally pictured him with fangs, a spiked collar, an electric guitar and a busty human girlfriend called Madonna.

SoA reacted with horror when it saw the character, declaring it would become the first video game firm with a core demographic of goths.

"There was a certain edge to him and this caused a divide," recalls Mr Harris.

"Since Sonic was created to [help Sega] succeed in America, SoA was given a mandate to make changes."

Japan sought a compromise whereby Sonic could be allowed to look menacing in certain regions, but the Americans saw the risk in allowing the company's mascot to have a split-personality, and they ultimately prevailed.

In the case of Mario, the writer recalls that the character was only invented because of a failed business deal, without which the console war may never have begun.

The idea of a Sonic with fangs was eventually revisited in 2008's Sonic Unleashed

Nintendo had been planning to release a game in 1981 based on Popeye in which the super-powered sailor had to rescue his girlfriend Olive Oyl by jumping over debris thrown by his arch-enemy Bluto.

But when negotiations broke down, designer Shigeru Miyamoto recast the idea as a gorilla chucking barrels at the Italian plumber.

"It was a blessing in disguise because Donkey Kong became the most successful arcade game of all time," says Mr Harris.

"It helped Nintendo weather the storm of the video game crash of 1983.

"And it ultimately led to Mario, his brother Luigi... and basically what made Nintendo such an alluring and intoxicating place to spend my childhood."

- Published17 June 2013

- Published4 June 2012

- Published23 June 2011