Whispers, secrets, and the return of anonymity on the web

- Published

A slew of new mobile apps aim to capitalise on a desire for anonymity in social applications

As our identities become more entrenched on the web, a slew of apps want us to return to an earlier era of anonymity on the internet. But can apps such as Secret - which has just launched on Android - really keep our identities, well, secret?

Think back to an AOL chatroom.

Wait for the modem to sing its song, click the connect button, find a room - and inevitably, the first question you're asked as soon as you log in is "a/s/l?" - age/sex/location.

In other words: "Who are you?"

For many people, this was the defining feature of the internet: anonymity. A place where screen names and loose identification protocols made the web, by default, an opaque place.

Today, our digital identities adhere ever more closely to our real lives, with Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram allowing real-time and often permanent imprints of our existence.

While alleviating one concern - identification - they have created another: is there any way to be open on the internet anymore, without fear of reprisal?

That is why a whole host of firms are arguing that it is time to return to, or at least make space for, anonymity.

The best version

"You look at all of these services like Facebook and Instagram, and they're all about let me show you the best version of me," argues Whisper co-founder Michael Heyward.

"It's essentially this highlight reel - Whisper is about showing people the behind the scenes stuff that we're not always comfortable posting on Facebook."

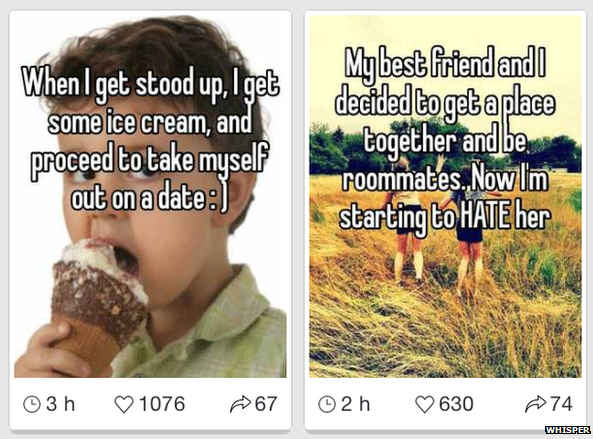

Whisper allows users to download an app and then post anonymous statements - everything from "do you like this outfit?" to "I'm worried I suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder". Users can then like statements they identify with or think are funny.

Whisper's dashboard lets users see the most popular Whispers, as well as allowing for sorting by category

Mr Heyward likens it to the Catholic concept of a confession - but a confession that also operates as a business. Whisper has raised over $60m (£36m) since being founded two years ago.

"I think we're really well positioned to own anonymity," he says.

Big business

But Mr Heyward isn't the only one to realise that both the intrusion of social networks into our "real lives" and the Edward Snowden US government spying revelations have led to an increased desire for anonymity on the web.

And, of course, capitalising on that desire for anonymity could be big business.

Secret, founded in October and launched in January by two former Google employees, Chrys Bader-Wechseler and David Byttow, has already raised $11.5m. Unlike Whisper, it accesses your phone's contacts and only shows you Secrets from friends or friends of friends.

It was a hit with iPhone users in Silicon Valley, where they posted juicy titbits, including news of which tech start-ups had been bought for millions and, most notably, broke news of layoffs at Nike, external.

And the app has just been made available in all countries both on iOS and Android.

Mr Bader-Wecheseler says that the duo didn't design the app with the concept of whistle-blowing in mind.

But now "we constantly ask ourselves is whistle-blowing important, and we think so".

Marketing gimmick

But thinking whistle-blowing is important and promising anonymity are two very different things.

"The problem with apps on mobile phones is that, well, it's a mobile phone," says Runi Sandvik, a technologist at the Center for Democracy and Technology.

"It's tied to you in some way or another and this identifier is often passed to the makers of these applications.

So even if these apps on their website are promising you anonymity, if asked or required they will hand over your information to law enforcement."

Some users of Secret have used the app to leak corporate news, others for mundane reasons

Ms Sandvik says that promises of anonymity are thus essentially a "marketing gimmick" because "you don't want to advertise an app that promises semi-anonymity".

And it is not just users who could find themselves in hot water.

University of Maryland law professor James Grimmelman notes that Snapchat, the self-deleting photo messaging app, recently got into hot water with US authorities over promises that images could not be stored.

"If users can be identified you cannot promise anonymity," he says.

He adds that the Nike leak also could cause legal issues, including leaking trade secrets and raising questions about insider trading.

Getting swept along

That's why perhaps "it's more about pseudo-nymity - the ability to have a real identity but being able to turn it off when you want to," says Dil-Domine Leonares, founder of an app called Breakr, which allows users anonymously join chatrooms based on their location.

That is a sentiment echoed, in some part, by Secret's founders, who insist the app isn't all about whistle-blowing.

"Facebook trained us to curate our identity - I think Secret can train us in empathy," says Mr Bader-Wechseler.

But that assumes - or presumes - that what people have to share is not mean, or slanderous, or just simply banal.

Whisper co-founder Michael Heyward faced questions over the social purpose of the app at TechCrunch

One recent Secret read: "Just spent 45 min trying to teach my cat a trick. He didn't get it. We'll work on it tomorrow."

Not exactly the stuff that moves mountains.

But then again, scroll down a bit and I found "Twitch.tv is rumored to have been acquired for $1b. Any big paydays for non-execs?" - something a bit more up my alley as a technology journalist.

Scroll down once more, this time on Whisper, and I found out that the ex-wife of a prominent technology executive was now dating.

And therein lies the question: are these apps about sharing feelings that can't be expressed publicly, leaking corporate secrets, or, simply trading in something that pre-dates the iPhone: gossip?

There's also the less philosophical, more practical issue, the word that is almost never spoken in the bubbly world of Silicon Valley: profits.

"We think about it every now and then but we haven't invested resources in solving this problem," says Mr Bader-Wechseler.

- Published30 April 2014

- Published11 March 2014

- Published4 December 2013