Net neutrality - should you care about it?

- Published

What exactly is net neutrality and should you care?

Net neutrality is a term you may have heard but, if asked to explain it in a pub, you might struggle.

You might also question how relevant it is to you and what you do online.

Advocates of the principle argue that the debate about how networks operate is fundamentally one about the future of the internet.

Ahead of a crucial US vote on the subject, the BBC has compiled a guide to all you need to know about net neutrality.

What is net neutrality?

Anyone who has ever looked with envy at the first-class carriages on a crowded commuter train - and wondered bitterly why a few get to travel in comfort while the rest are crammed against each other's armpits - will have a good basic understanding of net neutrality.

On the net neutrality train, all passengers (ie data) would be treated equally, with no special carriages for those able to pay.

This long-held principle that all traffic on the network should be treated the same goes back to the very dawning of the web and for many enshrines the whole ethos of an open internet, free from corporate control.

Those in favour of net neutrality argue that the internet service providers (ISPs) that provide the pipes for content should just run the networks and have no say over how and what content flows to consumers, as long as it is legal.

But ISPs argue that a tiered internet - where those content providers prepared to pay can go in an internet "fast lane" - is inevitable in today's data-hungry net world.

Why is net neutrality in the headlines?

FCC chairman Tom Wheeler has been forced to rethink the rules following the court case

Much of the current debate was kickstarted by a landmark case in the US in January, which saw ISP Verizon successfully challenging the US Federal Communications Commission (FCC) over its net neutrality policy - known formally as the Open Internet rules.

The Court of Appeals struck down two of the three open internet rules, effectively leaving regulation in limbo and opening the way for ISPs to start charging fees to carry bandwidth-hungry data on its networks.

And charge they did. In March Netflix reluctantly agreed to pay a fee to Comcast to improve the speed at which its service reached consumers' homes.

The changing landscape forced the FCC to rethink its rules, and leaks of what it proposed emerged in April.

The part of the rule change that has sent the industry into uproar is a proposal for so-called fast lanes, allowing ISPs to charge content providers as long as the terms were "commercially reasonable".

The details of what the FCC proposes will be revealed on 15 May.

It is worth noting that, at this stage, these are just proposals and that the full rules are not likely to be implemented before the end of the year.

What has been the reaction to the proposed changes?

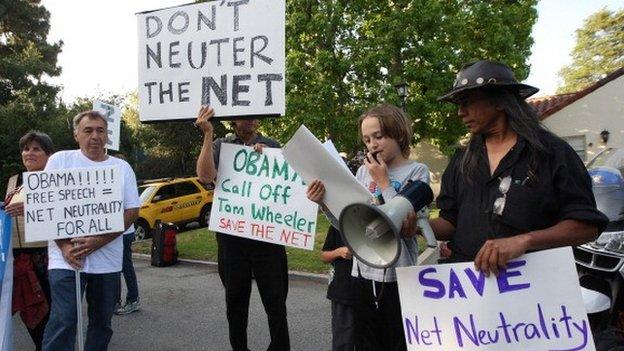

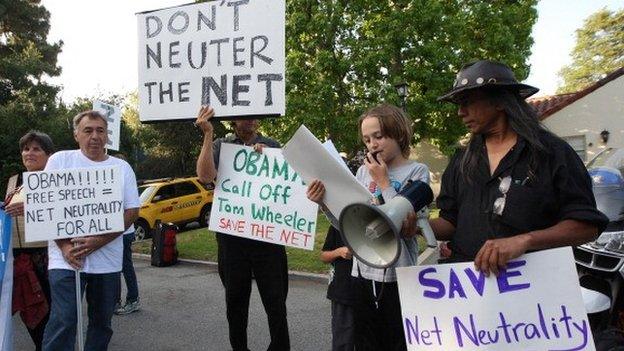

People are protesting over the proposed changes

It would be fair to say that the FCC has found itself at the centre of a considerable storm since details about the proposed changes leaked.

Chairman Tom Wheeler's morning mail pile has grown considerably, with his recent correspondence including a letter signed by more than 100 tech firms with some of biggest names in the industry - Google, Amazon, Twitter, Facebook - offering their support. The letter calls on the FCC to protect users "against blocking, discrimination and paid prioritisation".

This was followed by a very similarly worded letter from some of the most high-profile US venture capitalists and another from more than 80 advocacy groups.

Meanwhile, the FCC's main consumer hotline seems to have been overwhelmed by messages about the forthcoming changes - and now asks callers to write an email to the commission if they are calling about net neutrality.

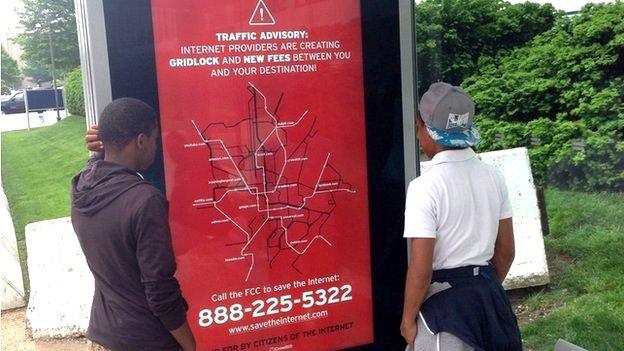

And to really hammer the message home, a growing number of protesters are gathering outside the FCC headquarters in Washington ahead of the scheduled vote on the proposals by the five commissioners.

Already two of them have got cold feet and suggested that the vote be delayed.

What are the arguments for changing the rules?

Are internet fast lanes inevitable in today's data-hungry world?

ISPs argue that the internet today is a very different beast from that of the early days when the net neutrality principle was enshrined.

Who then could have predicted that we would all be watching video content on our computers and mobile devices?

Carrying such data obviously costs more and ISPs argue that the costs of carrying such bandwidth-hungry services can no longer be borne by them alone.

They say that concerns that they plan to block content or degrade network performance are unfounded and that data discrimination in order to guarantee quality of service is actually something consumers should want.

What else could the FCC do?

Consumer advocates are urging the regulatory body to take more drastic action and reclassify internet service providers as a telecommunication service.

By doing so, the internet would be treated more like a public utility, such as gas and water, and therefore subject to heavier regulation.

It would mean, say the advocates of net neutrality, that the FCC had more teeth when it came to enforcing net neutrality.

What's the view about net neutrality outside the US?

Europe is at odds with the US.

In April, the European Parliament voted to restrict ISPs from charging services for faster network access.

It also ruled that mobile and broadband network providers should not be able to block services that competed with their own offerings.

There are some more legal hurdles for the vote to pass but it could become law by the end of the year.

Slovenia and the Netherlands have already enshrined the principle in their national law.

And in Brazil, a new law has been signed by President Dilma Rousseff which establishes that telecom companies cannot change prices based on the amount of content accessed by users. It also states that ISPs cannot interfere with how consumers use the internet.

Meanwhile, neighbouring Chile was the first country to pass net neutrality legislation, back in 2010.

Why should you care?

Depending on which way the decision goes, it could either hurt your wallet or your watching habits.

If net neutrality is upheld, ISPs could decide to pass on the cost of delivering bandwidth-hungry up the cost of services to pay for delivering faster bandwidth - and raise the monthly fee they charge for net access.

Users may get a bill that reflects their usage, with those using video-on-demand services being charged more.

If, on the other hand, ISPs get their way and are able to start charging fees for prioritised access to content then users may find that those websites not in the fast lane are slow to load.

Some fear that ISPs might even block access to rival services or slow them down so much as to be unusable.

Consumers could also be charged more by the content providers forced to pay more to get their services to them in quality.

Anyone thinking this is a US-only issue should note that, following its agreement to pay a fee to Comcast and Verizon, Netflix put up the price for its monthly streaming service in Europe as well as America.

- Published14 May 2014

- Published9 May 2014

- Published8 May 2014

- Published28 April 2014