Why does sexism persist in the video games industry?

- Published

Going off like a bomb: Ubisoft's decision to eliminate female assassins from Assassins Creed was met with anger

Is creating female video game characters too much work?

That might sound like a rhetorical question, but it was actually one of the main topics of discussion at this year's E3 conference - the video game industry's biggest event, which ended on Thursday.

The issue arose after James Therien, technical director at European gamemaker Ubisoft, told trade publication VideoGamer, external that the latest instalment of Ubisoft hit Assassin's Creed would not feature any playable female characters because it would have "doubled the work".

The reaction was swift - and negative - especially when a former Ubisoft developer questioned, external how much work would be involved.

"The message from the industry is that men come first," says Jayd Ait-Kaci, a gamer from Canada who started the hashtag #womenaretoohardtoanimate, external, which was picked up widely.

Reaction to Ubisoft's decision on social media was primarily negative

"#womenaretoohardtoanimate when you throw all your efforts into putting them in situations where their clothes are strategically ripped off" wrote @emilyrwanner, external.

But what left many scratching their heads was that Ubisoft had already included female assassins in earlier instalments, and that the firm has emphasised diversity, tapping actress and gamer Aisha Tyler as its host at E3.

Lara Croft of the Tomb Raider games is one of the most high-profile female video game characters

So what's going on: is the video game industry progressing - or regressing - when it comes to female representation?

Damsels in distress

Of course, the issue of gender ratios in video games is not a new one - but it did seem to be on more observers' minds at E3 this year, with observers tweeting about a lack of female characters, external in Sony's presentation and videogame site Polygon publishing an article titled "There were more severed heads than women presenters at E3 2014, external".

Studies have consistently shown that at least since the 1990s, the percentage of female characters in video games has remained steady at around 15%.

"It's amazing how little has changed," says University of Pennsylvania professor, Yasmin Kafai, the co-editor of one of the seminal books on gender in videogames, Beyond Barbie and Mortal Kombat, published in 2008.

Who plays video games in the US?

Most gamers in the US have been playing for an average of 14 years

Average gamer is 31 years old

48% of gamers are female

71% of gamers are 18 or older

53% of gamers play games on their smartphones

While there have been exceptions - Lara Croft, in Tomb Raider, or 14-year-old Ellie in The Last of Us - the most recent data found that only 4% of the main characters in the top 25 selling videogames of 2013 were female.

And even when female characters do exist, their representation is generally skewed.

"The research is pretty consistent that there are two types of female characters: the 'damsel in distress' or the 'ultimate warrior'," says Edward Downs, a professor of communications at the University of Minnesota, who notes that most "ultimate warrior" characters are depicted as hyper-sexualised.

Money on the table

The thought for a long time had been that since men were the primary consumers of video games, the gender balance was lamentable but not surprising if firms were simply designing games with their target audience in mind.

But the dynamics of who is gaming has steadily changed in the last five years, as women increasingly flock to video games, with the latest industry figures in the US showing that 48% of gamers are female.

Efforts by pioneers such as Anita Sarkeesian, who runs the website Feminist Frequency, external, which details sexual dynamics in games, have also brought increasing attention to sexism in games and the industry.

Anita Sarkeesian's efforts at Feminist Frequency to bring attention to sexism in the industry are widely cited

That has put pressure on video game firms like Ubisoft, Sony and Nintendo, among others, to fix the ratio in their games and to change the culture surrounding events like E3, once populated by "booth babes".

Although Ms Sarkeesian was subject to rape and death threats for her efforts, it does feel like "the industry as a culture feels less sexist than it used to," says University of Southern California professor Dmitri Williams.

That is partially because the video game industry realised they were "leaving a lot of money on the table by alienating women," he says.

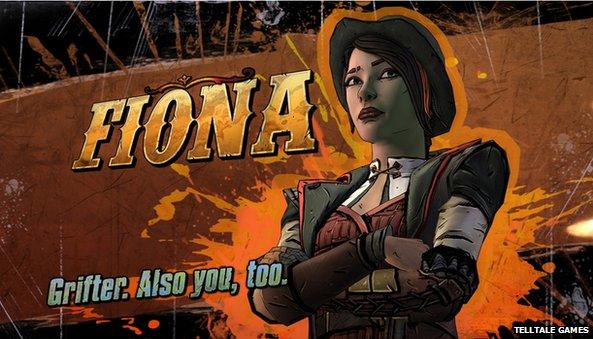

That has led to some inroads: Borderlands: The Pre-Sequel, Civilization: Beyond Earth, Evolve, and Dead Island 2 were all new releases at E3, external that either allowed one to play as a woman or had female protagonists.

The latest instalment of the Borderlands franchise features a female protagonist, Fiona

BioWare's third-person shooter game Mass Effect has been singled out for praise for its female characters

Developer crunch

Of course, there are caveats.

While the percentage of female gamers has increased, that has been primarily due to the rise of mobile games, which often do not have characters. For instance, 60% of popular smartphone game Temple Run's players are female (although that game does allow one to play as a female character).

The gender ratio of players of so-called hardcore games, like first-person shooter games such as Halo, is generally disproportionately men, says Prof Williams, who also runs a game analytics firm, NinjaMetrics

It is those games - FPSs, in industry speak - that many observers see the industry regressing, not progressing.

"I think we're starting to see in some cases at least in some genres an even larger gap in the types of players," says Prof Downs.

The need to constantly refresh successful franchises to boost console sales has also put pressure on developers to churn out games at ever faster speeds.

That time crunch is a problem, says New York University professor and game designer Katherine Isbister, because most developers are men.

Developers "tend to create things that are similar to things they're seeing and playing so there's a feedback loop," she says.

Two steps forward

This brings the industry to a bit of a chicken or egg problem, at least when it comes to the hardcore games on consoles.

"Are women not playing hardcore games because they don't like them? Or because they feel alienated?" summarises Prof Williams.

Ubisoft says it is committed to diversity, and in a statement to the BBC did not comment on whether or not the decision to exclude female assassins was an economic choice or one based on user statistics.

Jenny Haniver posts audio recordings and screenshots of the abuse she receives while playing Call of Duty

But the case of Jenny Haniver could prove instructive.

Ms Haniver plays Call of Duty - a FPS game - daily with her friends, as she has done for years - even though she is often subjected to harassment when men discover that she's a woman, as she told the BBC in 2012.

But, recently, Call of Duty introduced an option to play as a female character.

Now, she says "everyone I know when given the option will play as female characters" - including some men, who have also lobbied for more female characters, external and a reduction of both hypersexualised female and male characters.

"The more we're normalised and shown as protagonists, the more women are going to want to play games," she says.

- Published5 June 2014

- Published16 January 2013

- Published4 June 2012