Can Iraqi militants be kept off social media sites?

- Published

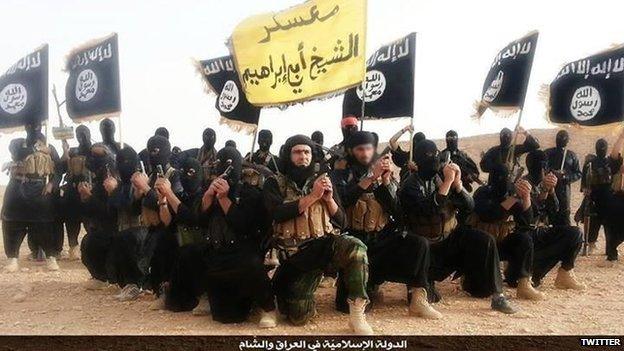

Isis fighters have posted triumphant photos on Twitter

Alongside their efforts on the ground, Jihadist fighters in Iraq have waged a propaganda war on social media in the past few weeks, posting graphic images, promotional videos and updates of their campaign to overthrow the government.

Isis, the group at the heart of the insurgency, has even deployed an Android app that posts tweets automatically on users' behalf (since removed), and co-ordinated hashtag campaigns to get its content trending on Twitter.

The Iraqi government responded by blocking social media sites and, in some provinces, barring access to the internet entirely.

But some of the most active Islamist social media accounts are still live, including those urging Muslims in other countries to join the struggle.

The three men featured in a recent Isis recruitment video, which was posted on YouTube but has since been removed, are all still on Twitter using military pseudonyms, the BBC believes.

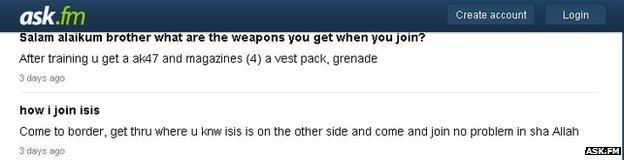

An Islamist purporting to be British offered tips to those thinking of joining Isis on Ask.fm

But why have these accounts not been removed?

The BBC spoke to a number of social networks, all of which said they did not actively monitor their sites for content promoting terrorism, but rather responded to requests from governments and individuals to remove offending material.

A spokesperson for Twitter said the company would remove a reported post that violated its rules.

Some Isis Twitter accounts feature graphic depictions of violence

Twitter's terms ban threats of violence and the "furtherance of illegal activities" on the site.

It added that Twitter does not monitor media reports on inflammatory posts.

Extreme content

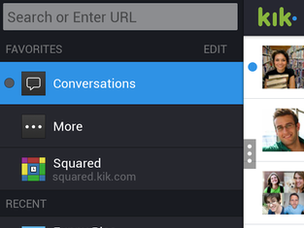

Many of the militants on Twitter redirect users to their Kik accounts.

Kik, a personal messaging service similar to WhatsApp and Blackberry Messenger, allows users to have group conversations.

Kik allows users to have group conversations and surf the web

It can also be used to send free private messages.

Kik, which boasts 120 million users, could not be reached for comment.

Another tool being used is Ask.fm, a site that allows users to pose questions to an individual.

One Ask.fm account offered advice on how to join Isis fighters in Iraq, as well as what weapons one could expect to be equipped with on arrival.

Ask.fm, which has previously been the subject of a cyberbullying controversy, told the BBC a few days ago that it did not allow posts containing calls to violence and criminal activity.

"Based on media reports, the company is now assessing several profiles to evaluate their compliance with Ask.fm terms of use," a spokesperson said.

"When requested, Ask.fm is ready to co-operate with law enforcement agencies in the framework of the official investigation.''

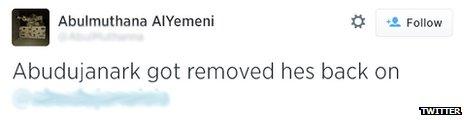

Many Jihadists are routinely switching Twitter accounts

However, almost a week later, Jihadist accounts on Ask.fm are still active.

Other social media sites, notably Facebook and YouTube, have been more successful in removing extreme content.

When asked about its policy towards extreme content, YouTube owner's Google said it removed videos "when flagged by our users".

A spokesperson added that it also terminated any account registered by a member of a foreign terrorist organisation - as designated by the US secretary of state - and used in an official capacity to further its interests.

"We allow videos posted with a clear news or documentary purpose to remain on YouTube, applying warnings and age-restrictions as appropriate."

The BBC understands that Facebook, whose rules ban terrorist organisations and those promoting extremism from posting on the site, removes content when reported by users.

BBC journalist Thomas Martienssen, who was been monitoring militants on social media, says all the Facebook accounts with which he was in contact were taken down earlier in the week.

However many accounts which are closed by social media companies soon return under a different name, with militants publicising the change on various platforms.