Tomorrow's cities - what happens when lights go out?

- Published

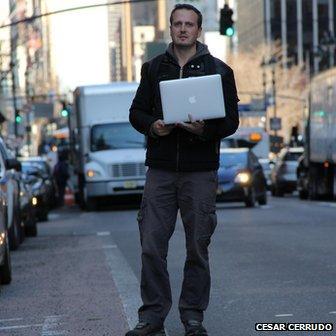

Ken Munro explains how hackers can attack cities

In the first of an eight week series of articles about how technology is changing our cities, Jane Wakefield asks whether a city that is plugged into the network is vulnerable to hackers.

The nightmare scenario that has had government leaders and city bosses biting their fingernails for decades has come true. Chicago has been hacked.

The traffic lights have ceased to function, leaving roads in chaos. The city has no electricity. It is in the hands of the hackers.

If the scenario sounds far-fetched, you'd be right - for now at least.

It is in fact just a scene from recently released video game Watch Dogs, which features a near-future Chicago in which players control Aiden Pearce, a highly skilled hacker who can break into the urban operating system that controls the infrastructure of the city.

But as cities become ever more connected to the network, with sensors in everything, including the roads, traffic lights and even the bins, could it really happen?

While researching the game, Ubisoft's brand director, Thomas Geffroyd, was surprised by how easy it was to hack a city.

If hackers can control the traffic lights, chaos could follow

"We discovered that there are lots of systems that have been in cities for 20 or 30 years, and they were installed without security in mind," he says.

"If you find a weak point, you have access to everything, and it is really easy to hack into the system - you simply use a search engine that looks for devices rather than web addresses and then use default passwords and logins to get in.

"The worst case scenario, the city is without electricity and the traffic is at a standstill."

Cities under attack

•Security firm F-Secure has seen a rise in the number of attacks on so-called Scada (supervisory control and data acquisition) systems used by the gas, electricity and water industries

•In July it warned that malicious software from the Energetic Bear hacking group, which some believe has ties to the Russian government, could have infected energy and industrial firms around the world

•Hackers can find the system they want to attack via Shodan, a search engine for Scada systems

•Then they can target the laptop of staff, via phishing emails, to inject malware and take control of the machine that talks to the Scada system

•Energetic Bear attacked the website of a software vendor that supplied Scada equipment, injecting it with malware and waiting for someone to install it in their systems

•The worry is that criminal gangs are starting to infiltrate such systems and offer them for sale on the dark net

•Others may take over systems and demand payment to hand back control, according to F-Secure

Source: F-Secure

It is a scenario that Ken Munro, an ethical hacker and expert in industrial control systems known as Scada (supervisory control and data acquisition) is familiar with.

Going back more than a decade, he did security testing on a set of traffic lights in a large UK town that he doesn't want to name and found that someone with a bit of knowledge could change the lights on demand and cause chaos.

"Fortunately that particular set of lights was fixed as a result," he says.

But as more and more cities introduce smart traffic lights and roads that speak to each other and are connected to the network, the problem is only going to get worse.

"The movie Die Hard 4 is not particularly far-fetched," Mr Munro adds.

Drone attack

Lack of encryption in how traffic lights communicate could open door to hack attacks found Cesar Cerrudo

That film was inspiration for security researcher Cesar Cerrudo when he set out to hack a real-life city.

"Watching scenes where terrorist hackers manipulate traffic signals by just hitting Enter or typing a few keys. I wanted to do that," he admits in a blog post, external.

He goes on to outline how close he got when he discovered a major security flaw - no encryption on the wireless connection that allows road sensors to communicate with traffic lights.

Such systems are installed in about 40 US cities, including San Francisco, Los Angeles and New York, as well as other cities around the world.

The sensors feed data about traffic flow to the boxes that control the traffic lights, in order to allow the lights to be adjusted according to whether traffic is heavy or light.

Mr Cerrudo says: "By exploiting the vulnerabilities I found, an attacker could cause traffic jams... it's possible to make traffic lights stay green for more or less time, stay red and not change to green. It is also possible to cause electronic signs to display incorrect speed limits and instructions.

"These traffic problems could cause real issues, even deadly ones by cars crashing or by blocking ambulances, firefighters, or police cars going for an emergency call."

He tested his theory using a drone and even visited the cities of Seattle, New York and Washington to do some passive testing - although "no hacking and nothing illegal", he stresses.

Although he informed the makers of the system and the Department of Homeland Security about the problem, he says: "I couldn't convince them that there was a serious issue." although the vendor has since moved to improve security.

Miniature hacking

The tiny city that is under constant cyber-attack

Ed Skoudis knows all about the vulnerabilities in cities, as his own is under constant attack.

From the gas pipes that run beneath it to the traffic lights, electricity supply and even the newspaper office and internet service provider, never a day goes by when the city is not being bombarded.

Luckily though it exists only as a tiny 2m (6ft 6in) by 3m model and the hacks are intentional, designed to teach government and military how to fight back in such circumstances.

CyberCity, as it is called, is based in New Jersey, and those wanting to test their skills against it - currently the US government, the US military and some selected commercial organisations - do not have to be there in person. They can play the game in small teams over the internet and will be live-streamed video to see what the consequences of their actions are.

Everything in the tiny city is painstakingly lifelike.

"The physical infrastructure underneath it is based on real Scada systems. We are trying to replicate what exists now and modelling it as realistically as possible," Mr Skoudis says.

The hospital has better security than real ones though.

"We had to harden it, otherwise it would have been just too easy to attack. Real hospitals have other priorities - they are focused on care-giving, and security is low on their list of priorities."

CyberCity is constantly evolving to reflect the real world - so it now has a social network - called FaceSpace - and Mr Skoudis is considering setting up a radio station, a port and introducing smart meters.

The last is a nod to the fact that cities are getting smarter and, as they plug even more things into the network, they are going to have to make sure that they have skilled security experts in place to test the new systems as well as retrofit the older ones, says Mr Skoudis.

"We have a deficit of those people at the moment, but we are doing our darnest to bring those skill levels up," he says.

There will be no shortage of bad guys willing to test their skills.

"From young hackers just doing it because they can, to nation states wanting to bring a particular city to its knees, to criminals wanting to make it difficult, for example, to be chased through a city, there are plenty of people that may want to hack city systems," says Mr Munro.

There could be a little breathing space for the authorities though.

"Cities aren't that well connected now so such attacks will be limited to localised jamming or young script kiddies screwing up the traffic lights," says Mr Munro.

But as more and more cities, from Rio de Janeiro to Glasgow invest in city-wide sensors and control rooms into which all the data they generate is fed, so the hacking issue becomes more of a problem.

"If someone gets access to the data headquarters then it starts to get really scary."