MIT scientists develop sensor-operated robotic fingers

- Published

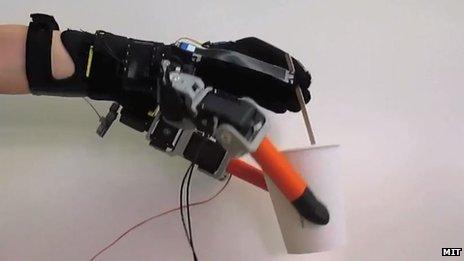

The extra fingers move in sync with the wearer's hand, the developers said.

Scientists at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) have come up with a robotic extension to the human hand they said could help with everyday tasks.

Researches said the extension - essentially, two extra "fingers" - could be used to grasp, leaving the hand free to do other tasks.

Worn around the wrist, it mimics the movement of the wearer's hand.

The next step, they said, will be a less bulky version.

The extra fingers developed by the team at MIT work using sensors attached to the human hand to measure the position of the wearer's fingers. An algorithm controls the output from the sensors to the robotic fingers, moving them in sync.

"Every day, we use various tools, say a knife and fork and we drive a car and, if we use these tools for a long time, you see that those tools are just an extension of your body," said Harry Asada, the Ford Prof of Engineering in MIT's Department of Mechanical Engineering.

"That is exactly what we would like to do with robotics, you have extra fingers and extra arms. If you have control and can communicate with them very well, you feel that they are just an extension of your body," he added in a video posted on YouTube., external

The device could leave the human hand free to perform other tasks, like stirring coffee, the researchers said.

The robotic fingers are at either side of the the hand - one outside the thumb, and the other outside the little finger.

"This is a completely intuitive and natural way to move your robotic fingers. You do not need to command the robot, but simply move your fingers naturally. Then the robotic fingers react and assist your fingers," said Prof Asada.

The developers said their work up until this point was focused on perfecting the posture and movement of the robotic fingers.

"But it's not the whole story," said graduate student Faye Wu, who presented a paper on the fingers this week at the Robotics: Science and Systems conference in California.

She said: "There are other things that make a good, stable grasp. With an object that looks small but is heavy, or is slippery, the posture would be the same, but the force would be different, so how would it adapt to that? That's the next thing we'll look at."

'Specialists'

One independent expert said that the device was most likely to appeal to specialists, rather than the mass market.

"Clearly, the military is interested in robotics, they are interested in building machines, like exoskeletons that allow people to run very fast for a long time," said David Bourne, principal systems scientist at the robotics institute at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh.

"But those things are inherently very expensive," he said, adding that devices need to have a "killer application" to work in the mass market.

However, Mr Bourne said that, after a lull, he has seen a resurgence in interest in robotics in recent years because of advances in the technology.

"You have better control and less awkward communication with the devices now," he said.

Professor Harry Asada said his team was working on making the device smaller and foldable

Prof Asada acknowledged the project had only yielded a prototype at this stage, but said he was optimistic about the possibilities it offers.

"We can shrink it down to one-third its size, and make it foldable," he said.

"We could make this into a watch or a bracelet where the fingers pop up, and when the job is done, they come back into the watch.

"Wearable robots are a way to bring the robot closer to our daily life."

- Published1 July 2014

- Published8 July 2014

- Published4 December 2013