How to make cyber scams go pop

- Published

Protecting people against cyber scams means knowing a lot about cultural icons such as Batman

If you want to spot an online scam then it pays to know your pop culture.

So says Chris Boyd, a veteran of the anti-malware world who spends his working life spotting and exposing cyber cons, online come-ons and web-based scams for security firm Malwarebytes.

"Increasingly the bad guys are drilling down into the cultural underpinnings so we have to do this too," he says.

The con artists who create the scams are experts at spotting a corner of modern culture ripe for their particular brand of exploitation. They do it because, ultimately, all the scammers want you to do is click on a link.

Hence their propensity for prompting an argument among already committed fans (1D versus The Vamps) or tickling a controversy (such as whether the batsuit worn by Ben Affleck in stills from the next Batman movie is inspired by Frank Miller's Dark Knight Returns or not).

Sometimes, he reveals, the scammers deliberately get it a little bit wrong just to get the fanboys and fangirls to react - which in the case of online scams would be to make them follow a link they think will give them a chance to refute a muddle-headed opinion. Instead, it takes them to a page that tries to install unwanted spyware or adware and maybe seeks to steal online credentials.

"We do make these things easy for the scammers," he said. "We need to educate people about the way to avoid falling victim to these things."

Classic scam #1: Chunky lover

In 2003 an episode of The Simpsons involved Homer using the chunkylover53@aol.com email address. To stop it being abused the writers registered the address and, for a while, replied to messages sent to it. In 2008 an enterprising cyber thief took over the address and scammed anyone who saw the address on a re-run and sent a message to Homer.

Social networks are the ideal places to get the flame wars going and Mr Boyd maintains accounts on any and every place that people can share, post, gossip and like.

One of the more recent trends has been scammers interposing themselves between customers who have had a bad experience and the company that is trying to help them out via social media.

One recent example of this, he says, involved the in-game currency and trading cards for EA's Fifa Ultimate Team football game.

"EA was using Twitter for customer support for complaint resolution so the bad guys set up fake EA Twitter accounts and auto-responded to actual complaints," he explains.

"They were barging in and saying: 'We can fix this. Just click this link'. It was, of course, a phish," he says.

Thankfully that scam was shut down pretty quickly because Twitter, like many other maturing social networks, has got a lot better at responding to reports of fraudulent activity.

But Mr Boyd adds that it used to be a lot harder to get the scams stopped.

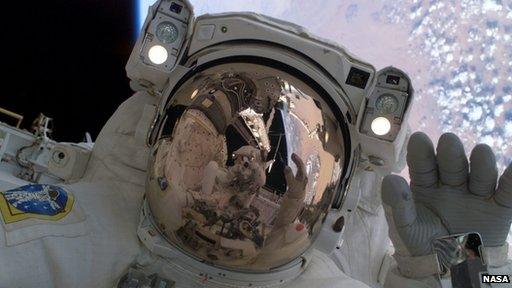

Classic scam #2: Nigeria's first astronaut

This con was a variation on the well-known 419 scam which typically asks for help to repatriate huge sums of cash from Nigeria. This version involved helping to get a Nigerian astronaut who was apparently stranded on the space station back to Earth.

"In the early days security researchers did not know anyone that worked on social networks and it was a nightmare getting a response," says Mr Boyd. "There was a huge run on Twitter a couple of years ago and now it's not as big a scam source as it was because they have really tightened up."

Having been a security pro for more than a decade he has seen many social networks come and go (MySpace, Bebo, Digg) and says they all tend to go through the same trajectory as they ride the wave of their popularity.

Typically, he said, any network that starts to become popular is so preoccupied by coping with the vast influx of users that they are easy pickings for the scammers.

That can make his job hard as they typically will not have anyone, apart from a few frazzled system administrators, worrying about security. That can slow down reaction times when he and other security folks try to shut down any scams that they spot.

"It's definitely better now than it was," he told the BBC. "Now they are much more responsive and they talk a lot more."

"There are times," he says, "when a company will not respond and you send an email into the void and you hope it will get to the right person."

What has also changed is the technical abilities of the con artists some of whom have got much better at making malware and spotting the technologies designed to stop them.

Classic scam #3: The Tumblr Giraffe

This con claimed that users of Tumblr would get a free giraffe if they re-blogged a link that supposedly came from the staff at the social media site. More than 60,000 people fell for the pitch which, thankfully, was fairly benign as it only took them to a charity donation page.

Now, Mr Boyd says, most malware will snoop around a system it has infected before reporting in to its creators. While snooping it is looking for evidence that it has landed in a honey pot - a computer system set up specifically to get infected.

Sometimes the malicious file will be made to sleep for a certain period of time to trick security systems into thinking the file is clean.

But for all the advances in the field of online crime, what has not changed is the propensity for people to fall for the come-ons.

"Right now body horror is a big thing for scammers on Facebook," he says. "Shock and gore has made a really wide resurgence in social media and for some reason a lot of people are lapping it up.

"People still look at these things in the hundreds and thousands despite everyone warning them not to," he says with a weary sigh. "It's always nonsense, there's never any video there."

What it can mean is that the scammers can hijack an account and then use it to get at a person's contacts and connections to make their next batch of messages more plausible and more likely to be read.

He doubts that roundabout of con and conned will ever end.

"They promise you all sorts and you get zero in return - that's the baseline deal for most of these things whether it's a website or app and that's been true for a lot longer than we have had computers," he says.

- Published6 August 2014

- Published29 July 2014

- Published22 July 2014

- Published3 July 2014