Def Con: The good, the bad and 'the Feds'

- Published

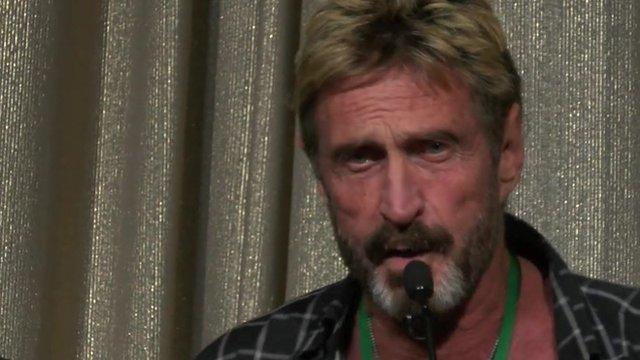

Dave Lee meets some of the hackers at Def Con in Las Vegas

The kids, aged between seven and 10 or so, are sat around in a semi-circle, as if ready to hear a bedtime story.

In front of them, a screen reads: "How many ways are there to break into a website?"

"You could steal someone's phone and get their password!" offers one young boy. "Very good," says the man leading the proceedings, with the skill of a well-honed children's entertainer.

"You could give someone candy and ask them to tell you their password," suggests another.

"Torture them!" shouts the most excitable boy, presumably not fully aware of what he means.

This room, set up to inspire kids into a career as a hacker, is a fringe event of Def Con, one of the biggest - and certainly the most notorious - hacking conferences in the world.

Here, the best, brightest and most dangerous hackers gather once a year, as they have for the past 22. It's a time to learn new skills and to network with people who refer to themselves by username only.

Somewhere, among the throngs of people, "the Feds" are watching, and with good reason.

Some of the things discussed here have the potential to disrupt a lot of lives. "Drink all the booze, hack all the things," goes the chorus of an unexpected rap performance during one presentation, a lyric that acts as an unofficial motto for what takes place at Def Con.

Hack me

Take the wireless village. It's here where a team of people are spending the conference attempting to discover as yet unknown vulnerabilities within 10 of the most widely used wi-fi routers in the world - the sort that's likely to be tucked away in the corner of your living room right now.

For 22 years, hackers have flocked to Las Vegas, for a rare physical gathering of cyber minds

"So far the competition has gone great," says Ted Harrington from Independent Security Evaluators, organisers of the event.

"We're looking at up to 13 new, serious issues."

Hackers do this, they say, to raise awareness about vulnerabilities so that manufacturers are compelled to do something about them.

But others would question the motivation. The whole point (and appeal) of Def Con is to find new ways to break things, and it's a passion that puts the personal data and well-being of people at risk.

But don't blame the hackers for that, says Jeff Moss - known as DarkTangent - the founder and organiser of Def Con.

"The technology is less secure whether we know it or not," he insists.

"We didn't go and redesign the product, the product was already insecure - all we're doing is pointing it out."

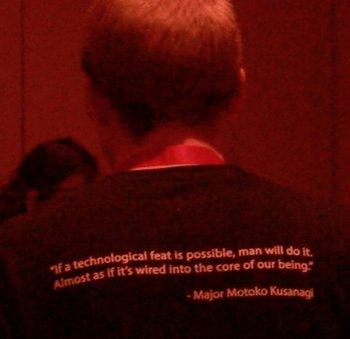

Many hackers are almost evangelical about their activities

It's a valid defence, and one that is supported by the Electronic Frontiers Foundation (EFF), a body much-loved among hackers.

The EFF campaigns for digital freedoms, and often lends legal support to hackers it feels are the victims of out-of-date laws.

"Unless one tries to find the problems among a community that is actually going to try and fix it, it's only going to be the hackers and the criminals that are going to find it.

"Now we've found these [bugs], they will be reported to the manufacturer and they will work on a fix."

Off limits

The BBC's interview with the EFF about wireless networking was cut short thanks to the protestations of one delegate unhappy with the media's presence at Def Con.

His hostility is shared by many here, unhappy at the attention the conference - bigger this year than ever - is starting to get.

It's only the past few years that organisers have allowed TV cameras in. In 2007, a reporter for US TV network NBC was quite literally chased out of the building after it was discovered she was secretly recording conversations in what hackers claim was an attempt to get them to incriminate themselves.

While less spiky these days, some parts of the show are strictly off limits - most significantly, the "Capture the Flag" area of the event, a huge room where the most hardcore hacking takes place.

Some of those who take part would lose their jobs if their employers found out they were associating with hackers, says the big chap on the door preventing the BBC from getting in - albeit very politely.

It sums up the conference's bizarre atmosphere. It is undeniably intimidating, even if individually delegates are extremely welcoming.

"Don't connect to any wi-fi networks," goes the advice. "Avoid any nearby cash points. And if you absolutely have to make a phone call, assume that people are listening in."

All these instructions come not from a security expert, but from a waiter in the hotel, who says every year staff suffer some kind of hack.

Hackers at Def Con get a Mohawk in support of the Electronic Frontier Foundation

Everything, and everyone, is fair game. In one room, projected onto a wall, is a live, constantly updating list of people who didn't heed the warnings - hacked usernames and passwords broadcast for all to see. An unsettling attraction to say the least.

'This is our time'

In years gone by, hackers were seen as a major pest - particularly in the eyes of companies that went to great lengths to protect their reputations.

But delegates here believe that attitude is well on the way to changing. Hackers are now being approached by companies who, far from wanting to have them arrested, instead want to offer them jobs in computer security.

In other words, if you're looking for a career with seriously good prospects in the years to come - you could do a lot worse than becoming a hacker.

"The energy, the opportunity… everybody's got full employment if you want it," says organiser Mr Moss.

"How many years this is going to last I don't know, but this is our time, this is our big opportunity, so let's do something with it."

- Published11 August 2014

- Published9 August 2014