James Foley: Extremists battle with social media

- Published

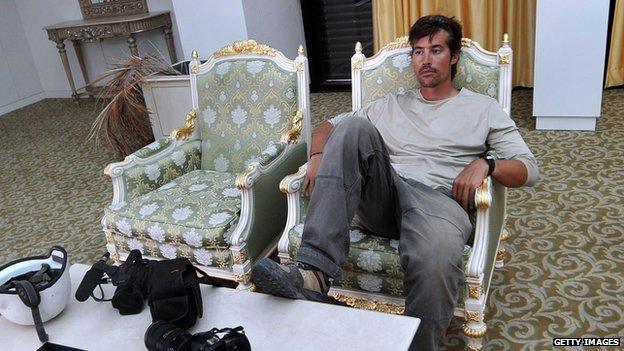

The spread of videos and images depicting the death of James Foley highlights the challenge facing networks

Just as Islamic State (IS) has swept across Iraq, so too has it swarmed over social media - using the platform with a sophistication never before witnessed in this way.

By sharing shocking images and video showing the killing of US journalist James Foley, IS has brought to the fore an issue many have warned about: that social networks are locked in a continual battle against extremists and the spread of shocking propaganda online.

Some experts say the networks are losing this battle, as more and more messages - many purporting to be from news agencies - flood services.

Others argue that social networks are doing what they can to protect users, and that measures in place to flag and remove content are effective.

Meanwhile, some have criticised social networks for putting more effort into detecting copyright infringement than they have into removing harmful material.

Here are the key issues.

What is happening?

After video of Foley appeared online, users on social networks urged others not to watch or share the clip.

But the effectiveness of IS's approach is staggering - mimicking the kind of efforts corporations would invest millions in for marketing purposes.

As the graphic video was circulated, some Twitter users started two hashtags - #ISISmediablackout and #DontShare - which sought to drown out messages showing the disturbing content, replacing it with images of Foley taken while he was working.

This app was used to post extremist messages on Twitter

But the reality is that extremists are finding new ways to circumvent the efforts of social networks trying to shut down accounts, a constant cat-and-mouse game that one source close to a major network described to the BBC as being a never-ending "game of whack-a-mole".

JM Berger is an analyst specialising in monitoring extremism on social media. He says that the online actions of IS - formerly Isis - rival the efforts of the finest social media marketing experts in the world. Indeed, the swift "brand name" change from Isis to IS has shown the effectiveness of the group's online message.

In spreading propaganda, one tactic utilised by the group stood out - a specially created app that, when willingly exposed on a person's phone, would tweet co-ordinated propaganda messages worded by IS, carefully timed not to fall foul of Twitter's spam filter.

In one example, 40,000 tweets were sent in this way in just one day. Given the vast number of tweets, and more importantly, the vast number of usernames being used to spread such messages, it was extremely difficult for Twitter to remove the material.

What can be done?

There is some progress. In the past week, Twitter has been acting to disable dozens of prominent accounts believed to belong to prominent IS members. It is making it harder for IS to spread its message, JM Berger told the BBC.

"IS has been struggling with how to respond to suspended accounts on Twitter.

"In reality, Twitter is one of the most permissive social media environments for them."

Some IS supporters have moved to alternative social networks, such as Diaspora

But he added: "While several dozen accounts have been suspended over the last few weeks, many more have remained online and many of those who have been suspended come back with new accounts."

One further tactic seemingly employed by IS supporters has been to temporarily deactivate their own accounts in an attempt to avoid a ban, although the BBC understands this has no impact on Twitter's ability to suspend inappropriate accounts.

Furthermore, noted Mr Berger, Twitter's ability to share links easily meant that while some IS members may be banned from Twitter itself, they were now beginning to appear on smaller social networks posting material that could then be passed on.

One network, Diaspora, appears to have emerged as the new network of choice for IS - it provides greater protections because of its decentralised nature.

Child abuse images can be blocked with technology - why not extremism?

The question of why extremist material cannot simply be blocked by websites is a question that is frequently asked - but has a complex answer.

When dealing with images of child sexual abuse, many services use sophisticated technology to automatically check content that is being uploaded against a database of known abusive content.

It means that images are, in theory, blocked before they are uploaded to the website in question.

PhotoDNA, a Microsoft product, is a market-leading piece of software for carrying out this work. The BBC understands that the same technology could be applied to images known to be spreading extremist propaganda, but that there are currently no plans to do so.

Microsoft offers PhotoDNA, a service for scanning - and blocking - content

For video on YouTube, Google has created ContentID, a system set up to detect when users upload copyrighted material. It checks uploaded content against a known database of footage and audio - most often music videos - and allows the copyright owners to either remove or place advertising on the video.

ContentID could be adapted to spot content known to be harmful - but Google is reluctant to put it to use in this way.

This is for a variety of reasons, but most significantly it is because while child abuse imagery is easy to categorise - there's no grey area; it's all illegal - violent or shocking material relating to terrorism is harder to define.

Often it is social networks that provide the only means of communication for those wanting to spread news of atrocities in hard-to-reach areas.

Facebook and Google have both in the past said that shocking images are permitted in cases where they are shown in a "news context", rather than for glorification.

Furthermore, the social networks are keen to argue that they should not be the guardians of what should be censored online.

But Mr Berger said: "As far as who should decide, Twitter and YouTube and all the rest are businesses, they are not public services or inalienable rights.

"Just as a movie theatre or restaurant can eject patrons who are harassing or threatening other patrons or engaging in criminal activity, online services have both the right and an obligation to take care of their customers and do the best they can to provide a safe environment."

How can I protect myself, or my children, from seeing this type of content?

This is difficult.

The very nature of social networks is that it is easy to share content, and the strength of Twitter and others is that information travels extremely quickly.

This presents a problem - a teenager browsing Facebook could stumble across the video of Foley's death in their news feed if a friend posted it. More worryingly, many videos posted to Facebook now auto-play, meaning a user does not have to click to start seeing the footage.

Online as well as off, tributes have been paid to James Foley

It's hard to avoid the possibility of seeing something upsetting, suggested security expert Graham Cluley.

"If your children are on the internet, it's an impossible task to completely shield them from some of the ghastly things going on in the world," he told the BBC.

"You can put your home computer in a shared room rather than a private bedroom, and have some oversight over what they're accessing online. But the proliferation of mobile devices makes it more difficult to oversee what your children are watching.

"Consider enabling parental controls that restrict which websites your kids can visit, but realise that it's an imperfect solution - it's perfectly possible that legitimate sites like YouTube, Twitter and Facebook might contain footage that many - young and old - would find harrowing."

Mr Cluley added that the best course of action for parents would be to spend time explaining what may have been seen.

"Talk to your children about the unpleasant and inappropriate things which can be watched on the net, and help them understand why it isn't cool to seek it out or to share it with their friends."

Follow Dave Lee on Twitter @DaveLeeBBC, external