Intel launches first 14-nanometre processor for thin fanless PCs

- Published

The Core M is the world's first commercially available processor with 14nm transistors

Intel has launched a generation of processors with the smallest transistors ever featured in a commercial product.

The Core M chip is the first in the family of Intel's next-generation Broadwell processors.

Intel had initially aimed to start delivering them to computer makers last year.

However, problems manufacturing the 14-nanometre transistors meant that the first chips were not sent until July.

The tech offers improved computing power and better battery life, according to Intel.

The firm has managed to make the physical size of the Core M 50% smaller and 30% thinner than that of the equivalent last-generation Haswell chip, which featured 22-nanometre (meaning billionths of a metre) transistors.

The firm said manufacturers would now be able to produce "razor-thin" fanless tablets - less than 9mm (0.35in) thick - without having to opt for a less powerful option, such as a rival ARM-based processor.

HP is one of the first PC makers to take advantage of the new computer chip

To coincide with Intel's launch at Berlin's IFA tech conference, several firms - including Acer, Asus, Dell, HP and Lenovo - unveiled laptop-tablet hybrids featuring the new processor.

The Core M is intended to be the most basic version of Broadwell. More powerful releases destined for desktop PCs and high-end laptops should become available early next year.

Experts said some manufacturers have had to delay product launches as a consequence.

But they added that Intel should not have lost business, because it still had a significant lead over its PC chip rival AMD when it came to CPU (central processing unit) development.

"Intel has a year-and-a-half to a two-year advantage over AMD in processing technology based on announced products," said Sergis Mushell, research director at the tech consultancy Gartner.

"Fourteen nanometre is not an easy thing to achieve - it's an industry first - so it's not the case that Intel is falling behind the rest of the industry.

"But where the delay is meaningful is the added time to deliver two-in-one fanless devices, which would have been very competitive with the [ARM-based] tablets that impacted sales of PCs."

Broadwell has taken longer to deliver than expected

Intel said it had been a "business decision" to produce the Core M chips first.

Tick time

According to the company, users should experience 50% faster computing performance and 40% faster graphics performance with Core M than a comparable last-generation chip.

However, applications may not see a matching speed increase because of the limitations of other components.

Intel said its tests indicated that a system that used to manage six hours and 20 minutes of video playback before running out of battery now lasted for more than eight hours.

Broadwell represents the "tick" in Intel's "tick-tock" development model, meaning that the major change is the shrinking of the processor's transistors rather than an overhaul of its architecture, as was the case with Haswell.

Transistors are a kind of switch that turns on and off as quickly as possible to let a computer carry out its calculations.

According to Moore's Law - an observation by one of Intel's co-founders - the number of transistors that can be placed on a chip for the same cost doubles roughly every two years.

The company acknowledged that it was becoming more difficult to hit the target.

"Moore's Law is incredibly challenging," said Kirk Skaugen, Intel's general manager of personal computing.

"Putting billions of transistors on nanometres of silicon is not something anyone has ever done before.

"It has got harder every generation over the last decade or few... and I expect it to continue to be very difficult, but we are confident as we look forward."

He added that one of Intel's key advantages was that it was the first and only company to shift over to "3D" or tri-gate technology, which had helped it shrink the transistors' size.

What are 3D transistors?

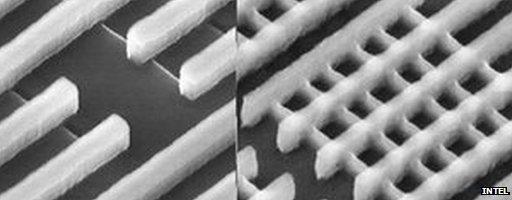

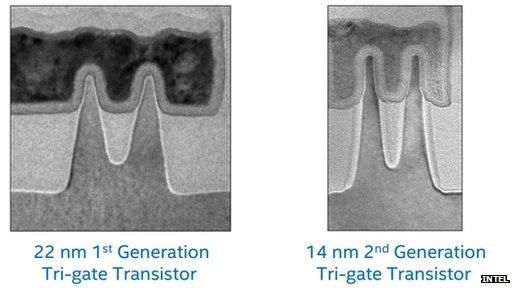

Traditional planar chip design (left) and Ivy Bridge's tri-gate technology (right)

Traditionally transistors have used "flat" planar gates designed to switch on and off as quickly as possible, letting the maximum amount of current flow when they are switched on, and minimum when they are switched off.

The problem is that the smaller the planar gates become, the more energy leakage occurs unless their switching speed is compromised.

Intel's solution has been to make the transistors "3D" - also known as tri-gate - replacing the "2D" gates with super-thin fins that rise up from the silicon base. Three gates are wrapped around each fin - two on each side and the other across the top.

The move was introduced in its Ivy Bridge family of chips in 2012, for which the distance between the nodes in the transistor was 22nm.

For reference, a human hair is about 60,000nm in diameter.

For Broadwell that gap has been shrunk to 14nm, which has been achieved in part by making the fins taller and thinner, and spacing them closer together. Since the revamped fins are more effective, fewer are needed than before, which also helps save on space.

The tri-gate fins on Broadwell transistors are taller and closer together than before

The next next-generation

One of the consequences of Broadwell's delay is that its successor may be fast on its heels.

Intel's chief executive Brian Krzanich confirmed in July, external that the first Skylake chips were still set to go on sale next year, offering further speed gains.

But one expert said that consumers should not put off a purchase.

"While I don't doubt that Skylake will be an improvement, I don't think it will be as big as an improvement as what we're seeing right now going from Haswell to Broadwell," said Ryan Smith, editor-in-chief of the hardware news site AnandTech.

"Furthermore, Intel is being really vague about when Skylake will arrive.

"There's a pretty good chance it will be towards the middle to the end of 2015, in which case you're not waiting just a few months but almost a year."

- Published16 October 2013

- Published4 June 2013

- Published23 April 2012