Cracking the problem of online identification

- Published

- comments

How do you go about proving you are who you say you are?

As more and more services move online - and fraud mounts - this is of growing importance not just to individuals but to the businesses and governments with which they interact. In many countries, the answer is an identity card, but that idea has met with lots of resistance in the UK.

Now the team which overhauled the government's many websites, bringing them all under the gov.uk address, thinks it has the answer. The Government Digital Service, fresh from winning all sorts of awards for gov.uk, is confident that an identity assurance system called Verify will be even more transformative.

Last week in a conference room inside the Treasury, I got a first glimpse of the new service from a group of people who couldn't be less like your average civil servants. Casually dressed, toting fold-up bicycles and laptops covered in stickers, they come across like programmers from an edgy start-up. Which is what GDS aspires to be..

They explained with some excitement that I was the first outsider to get a glimpse of Verify. The elevator pitch is that this is a one-stop shop for proving your identity for a range of government services, from renewing your passport or driving licence to paying tax.

The process of verifying your identity is not done by the government itself but is handed over to a range of outside companies. Right now, at the beta testing stage, this is limited to the credit rating agency Experian and the American company Verizon, which has an identity assurance business as well as a mobile phone network. Further on, the Post Office, banks and UK mobile phone operators will also be suppliers.

The GDS team gave me a demo of how the process worked, proceeding through a series of screens where you first choose which company to verify, and are then asked to give various personal details such as passport or driving licence number. You need to link your account to a mobile or landline phone number, which is then used to give you a one-time code before you proceed.

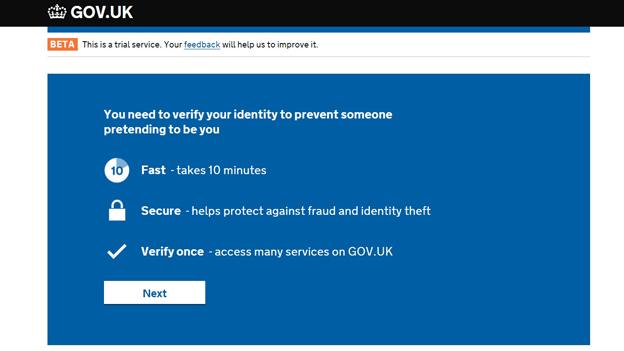

The whole process has been designed so that the first registration should be complete in 10 minutes. The promise is that once this is complete, you as the citizen will find access to public services more speedy while the government will have far more certainty that you are who you say you are. It all looks rather clever, and I emerged from the Treasury quite impressed. The UK is apparently leading the world with this scheme, with other governments and commercial organisations such as banks watching carefully to see whether it works.

Then, over the weekend, I tried the system at home. I'd been given special access to Verify , which starts its public test in October. I chose Experian as my identity checker and everything seemed to go smoothly, as I provided some details and supplied security answers to security questions - colour of first car, favourite food and so on.

Then quite suddenly up popped a message saying, "Unfortunately we have been unable to verify your identity at this time". Puzzled, I restarted the process with Verizon, only to end up with something similar. "You've been authenticated successfully," said the computer, "but not with a sufficient level of trust."

This was puzzling - I have been living at the same address for more than 20 years and, as far as I know, have a very solid credit record. So if I'm going to be rejected from this scheme, won't it end up excluding many of those who need online access to public services?

A trial service of the new site

I went back to the GDS team, who were puzzled. Without access to my personal data - and an important part of the process is that users are not handing over new information to the government - they could not explain why Experian and Verizon had rejected me.

But a spokeswoman tells me that my experience will form part of the feedback as they prepare to go live with Verify, which will have a very cautious launch. "We are not under any illusion that this is a finished product," she tells me. "This is a complex thing and we'll continue to test, monitor, and improve the system."

As the system is gradually rolled out across various public services, there are bound to be stories of angry users unable to make it work. There will also be plenty of questions of trust - do we really want a credit agency or a bank intervening in our relationship with the government?

But the GDS team is convinced that its open approach, where you experiment in public and learn from your mistakes rather than launch the "finished" product with a big bang, is the way forwards. Given the record of old school public sector IT projects, many of them multi-billion pound fiascos, you can see their point.