DarkHotel hackers targets company bosses in hotel rooms

- Published

Security researchers believe DarkHotel has targeted hotel guests for seven years

Companies are being warned about ongoing hack attacks that target hi-tech entrepreneurs and other corporate executives in their hotel rooms.

The campaign has been dubbed DarkHotel and is believed to single out specific senior staff when they log in to the net via wi-fi or an Ethernet cable.

The technique puts data at risk even if the employees are using encryption.

The attacks began in 2007, according to research firm Kaspersky Lab.

"The fact that most of the time the victims are top executives indicates the attackers have knowledge of their victims' whereabouts, including name and place of stay," said the Russian security company, external.

"This paints a dark, dangerous web in which unsuspecting travellers can easily fall."

The firm's research indicates the majority of the attacks to date have taken place in Japan but that visitors to hotels in Taiwan, mainland China, Hong Kong, Russia, South Korea, India, Indonesia, Germany, the US and Ireland have also been targeted.

It said that the effort was "well-resourced", but it was unclear who was responsible.

One independent expert said the hacks should not come as too much of a shock.

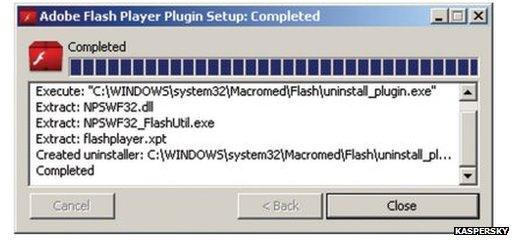

The malware was attached to legitimate updates for Adobe Flash and other software

"It's unsurprising given the high value of the targets," commented Dr Ian Brown, from the Oxford Internet Institute.

"This is perhaps a wake-up call to big company CEOs who weren't already aware that this kind of thing was going on."

Copied certificates

The scheme works by requesting that the targeted user installs an update to a popular software package shortly after they connect to the net.

Examples include new versions of Adobe Flash, Google Toolbar and Windows Messenger.

The installation files include legitimate software, but with the DarkHotel code added on.

To prevent the malware being detected, the hackers use certificates - the equivalent of a digital password, used under normal circumstances to confirm software is trustworthy.

The majority of the detected attacks targeted visitors to Japanese hotels

They were able to do this by taking copies of valid certificates that were protected by relatively weak levels of encryption, which they were capable of breaking.

Kaspersky said that examples of spoofed certificates that its researchers had found included ones issued by Deutsche Telekom, Cybertrust and Digisign.

The result is that the hackers can then employ other types of malware.

These are said to include:

Keyloggers - used to record and transmit a user's individual keyboard and mouse presses in order to monitor their activity

Information stealers - used to copy data off the computer's hard drive, including passwords stored by internet browsers, and the logins for cloud services including Twitter, Facebook, Mail.ru and Google

Trojans - used to scan a system's contents, including information about the anti-virus software it has installed. The findings are then uploaded to the hackers' computer servers

Droppers - software that installs further viruses on the system

Selective infectors - code that spreads the malware to other computer equipment via either a USB connection or shared removable storage. These targets appeared to be "systematically vetted" before being infected

Small downloaders - files designed to contact the hackers' server after 180 days. The belief is that this is intended to let them take back control if some of the other malware is detected and removed

The researchers said workers for electronics manufacturers, pharmaceutical companies, cosmetic makers, car designers, the military and non-governmental organisations had all been targeted.

They added that the employees had probably been identified by the last name and room number they were required to enter in order to access the internet, inferring that they must have had a separate way to determine their targets' travel dates, assigned room numbers and other details.

"The attackers were also very careful to immediately delete all traces of their tools as soon as an attack was carried out successfully," they added.

Royal Concierge

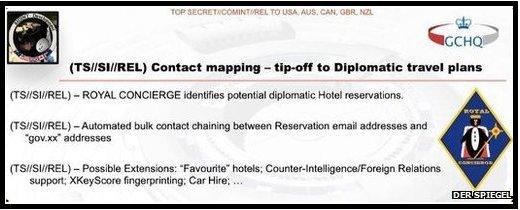

Dr Brown noted that GCHQ was believed to operate a separate but similar system of its own.

Last year Der Spiegel published allegations, external that the UK spy agency used a system called Royal Concierge to track foreign diplomats' reservations at at least 350 upmarket hotels around the world. Once a room was identified, it reported, agents would be deployed to monitor the target's communications.

Der Spiegel published allegations about GCHQ's hotel spying efforts as part of its coverage of whistleblower Edward Snowden's release of leaked documents

"It's not surprising that other countries would be wanting to do this," Dr Brown commented.

He added that one way to avoid the risk would be to ensure top-level employees were equipped with personal mobile hotspots, which use a 3G or 4G cellular data connection, rather than hotels' own internet equipment.

- Published6 November 2014

- Published29 October 2014