The rise of the Swedish cyborgs

- Published

The newly created cyborgs seem very happy to have been upgraded

Darkness had fallen over Stockholm as a group of eight people entered Swahili Bobs, a tattoo parlour in the dark alleys of Sodermalm.

By day there were tech entrepreneurs, students, web designers and IT consultants - but that night they were going to be transformed into cyborgs.

It may sound like the beginning of a science-fiction novel, but in fact it is a recollection of real events, by bio-hacker Hannes Sjoblad.

He organised the so-called implant party, which took place in late November and was one of several he has arranged. At it, eight volunteers were implanted with a small RFID (radio frequency identification) chip under the skin in their hand. Mr Sjoblad also has one.

He is starting small, aiming to get 100 volunteers signed up in the coming few months, with 50 people already implanted. But his vision is much bigger.

"Then will be a 1,000, then 10,000. I am convinced that this technology is here to stay and we will think it nothing strange to have an implant in their hand."

All the implants are done by professional tattooists

He finds volunteers through social media and hacker communities in Sweden, people that are used to tinkering with technology.

Currently the chip acts as a simple security interface, allowing users to open their door without a key, although to do so they need to buy a new door lock, which are at the moment still expensive.

With a tweak to an Android phone, it can also unlock the device.

But there is potential beyond that.

"I believe we have just started discovering the things we can do with this," Mr Sjoblad says.

"There is huge potential for life-logging.

"With the fitness-tracking wearables at the moment, you have to type what you are eating, or where you are going.

"Instead of typing data into my phone, when I put it down and tap it with my implant it will know I am going to bed.

"Imagine sensors around a gym that recognises, for instance, who is holding a dumb-bell via the tag in your hand.

"There is an ongoing explosion in the internet of things - the sensors will be all around for me to be able to register my activity in relation to them."

Digital tattoos take wearables to the next stage

Increasingly the lines between human and machine are blurring. People with missing limbs are routinely fitted with bionic ones, which are getting ever more sophisticated. People think nothing of getting an artificial hip or laser surgery to correct vision problems.

And last year, Google released contact lenses that can monitor glucose levels in an effort to provide better diagnostics for diabetes.

And of course wearables - from smart watches to gadgets such as Jawbone's Up or the Fitbit - are getting increasingly clever at monitoring a range of body functions from heart rate, calorie intake and sleep patterns.

But already firms are thinking beyond wearables.

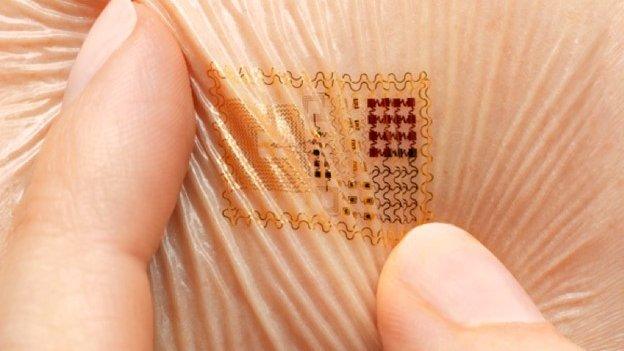

BioStamp is a digital tattoo developed by US firm MC10. It can be stamped directly on to the body and collects data on body temperature, hydration levels, UV exposure and more. As with other wearables, the data can be uploaded

Meanwhile another US company, Proteus, has developed a pill with an embedded sensor that works in tandem with a patch worn on the skin and, when swallowed, measures a range of body functions.

"These kind of things are already here," says David Wood, head of the London Futurists.

"The real question is whether they can work better if they are on our skin or inside us, and one of the big advantages is that we can't forget them like we can a phone or a wristband."

He doesn't think implantable technology is ready for the mainstream quite yet, but he does think that the time is definitely ripe for a debate about it.

When mass vaccination programs were introduced, there was suspicion about them

"Some people are horrified by this. They see it as completely crazy and have a deep unease about where technology is taking us and we have to be sensitive to people's feelings.

"Years ago there was fear over vaccinations and now it seems perfectly normal to have cells injected into us. That is an early example of bio-hacking"

Mr Sjoblad also hopes that his implant party will spark a conversation about our possible cyborg future.

"The idea is to become a community that is why they get implants done together," he says.

"People bond over the experience and start asking questions about what it means to be a man and machine.

"Curiosity is one of the biggest drivers for us humans. I come from a maker hacker culture and I just want to see what I can do with this."

For those who decide life as a cyborg isn't for them, the procedure Mr Sjoblad uses is reversible and takes just five minutes.

But he has no intention of removing his.

"We've been putting chips in animals for 20 years," he points out.

Now it is the turn of the humans.

"This is a fun thing, a conversation starter. It opens up interesting discussions about what it means to be human. This is not just for opening doors."

- Published28 November 2014

- Published30 October 2014

- Published18 March 2014