Child abuse database containing millions of images to launch

- Published

UK primes child abuse search tool

Data taken from tens of millions of child abuse photos and videos will shortly be used as part of a new police system to aid investigations into suspected paedophiles across the UK.

The obscene material was seized during previous operations.

The project, called the Child Abuse Image Database (Caid), will be launched by the Prime Minister at an internet safety event on Thursday 11 December.

But one expert warned its success depended on it being properly staffed.

Image Database

BBC News was given exclusive access to the database while it was under development.

It is intended to avoid offices duplicating each others' efforts when cataloguing identical copied images.

It was created by a team of coders working in a grey, concrete office block in central Gothenburg, Sweden.

They suggested the project would transform the way child abuse investigations were carried out in the UK.

Caid will try to match newly seized images to previously categorised examples

"We're looking at 70, 80, up to 90% work load reduction," said Johann Hofmann, law enforcement liaison officer for Netclean, one of the companies involved.

"We're seeing investigations being reduced from months to days."

Two other tech firms - Hubstream and L-3 ASA - have also been involved in the effort, which is backed by a two-year, £720,000 contract.

Unidentified victims

Detectives in the UK often seize computers, mobile devices or USB memory sticks with hundreds of thousands of images on them.

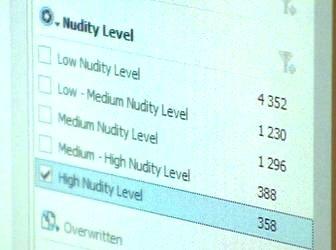

Caid will help automate the categorisation of child abuse imagery

At present, they have to go through the images manually one by one to categorise their severity and start a prosecution.

It can mean some material is never analysed, meaning new victims are not identified and cannot be rescued.

Recently, the children's charity NSPCC said it was gravely concerned about a lack of police forensic experts. It claimed that forces were seizing hundreds of computers each year, but didn't have the staff to examine all of them.

Mr Hofmann said the software would help automate more of the process.

"We want investigators to spend more time looking at the new material, instead of looking at the same images over and over again," he explained.

"Because we know that these images are typically traded and the same images appear in investigation after investigation."

Digital finger print

To help compare the images, Caid makes use of a unique signature assigned to each one - known as a hash value - the equivalent of a "digital fingerprint".

Detectives will be able to plug seized hard drives into the system so they can be scanned and their contents similarly encoded to see if the resulting signatures match.

Other techniques, including object matching and visual similarity analysis, are also employed.

The system should be able to identify known images, classify the content, and flag up those never seen before within minutes.

In a demonstration seen by the BBC, a green flag was triggered by innocent images, while known images of abuse were flagged red.

Caid will also be able to use GPS data from photographs to pinpoint where they were taken.

"Local investigators can spend more time being more victim centred, trying to find new victims," said Mr Hofmann.

Detectives will also be able to upload new, unfamiliar images of child abuse to a central computer server so that colleagues elsewhere in the UK can help try and identify those involved.

Tom Simmons, a former senior child protection officer who also worked at the National Crime Agency's Child Exploitation and Online Protection Centre (Ceop), said the initiative should lessen pressure on officers by reducing the amount of material they have to see.

Caid can identify GPS data linked to stored photos and videos to help indicate where they were made

"It's horrendous at times, clicking through image after image," he said.

He says a lack of resources, the harrowing nature of the material, and the scale of the problem can cause burn out.

"There could be hundreds of thousands, even millions of images on that hard drive that the officer may have to go through," he said.

"You could be seeing children effectively being tortured - that does become very difficult sometimes to get those images out of your head."

'Fizzle out' risk

But some experts in the field have their doubts about Caid's potential.

A similar system, called Childbase, was launched in 2003 by Ceop and the Home Office.

It contained seven million images and used ground-breaking facial-recognition software.

It was rolled out to police forces across the UK, but in 2011 it was switched off.

Sharon Girling received an OBE for her work on the scheme. She believes it failed because of a lack of trained officers.

Ms Girling warns that Caid could be short-lived unless it is properly resourced

"We have increased numbers of offenders since 2011. How the heck are we going to get sufficient officers today?"

She fears that Caid may "fizzle out" unless it is properly resourced.

"Childbase ceased to exist because of a lack of resources, because there weren't sufficient officers."

"I can only see that happening again with Caid, as much as I don't want that to happen, I fear that it may well do".

- Published6 August 2014

- Published17 October 2014

- Published4 August 2014

- Published18 November 2013