CES 2015: Should we be tracking our children?

- Published

We can't hold our children's hands forever but is there ever a need to track them?

There are trackers in all shapes and sizes on display at this year's Consumer Electronics Show - some aimed at children and the elderly, others at pets. But should we be tracking people?

"A parent should never solely rely on a device alone. This will only give a false sense of security," said Peter Bradley, director of services at the UK charity Kidscape, speaking to the BBC when LG launched Kizon, a tracker for children, last summer.

"There are ethical points to consider to. How can a child develop their own coping strategies knowing a parent is watching over them?"

Elderly parents may also object to their grown-up children tracking their movements, even with the best intentions around safety in the home.

Raising alarms

Keeping track of an elderly parent may provide comfort to the children, but what about privacy?

Start-up Lert.ly, founded by John McKinley, is a monitoring system aimed at the over-60s. It offers motion and door sensors as well as wearable alarms for older people, communicating data from within the home via wi-fi.

Sensors registered both "passive and active" motion, he said at a CES showcase on Monday.

This monitoring could include, for example, raising an alert not only if the person had not moved for a while but also if they appeared to be going to the bathroom a lot - a possible indication of a urinary tract infection, Mr McKinley said.

But is it a huge invasion of privacy?

"The industry really wants this to take off, but it remains to be seen whether children and the elderly really want to be tracked," said Michael Gorman, editor in chief of tech news site Engadget.

"It feels slightly nefarious, but generally there is a market for it."

Moral issues

The tracking devices come in all shapes and sizes

The industry itself seems divided over the issue.

Jeremy Fish said his company, TrackR, advised against using their devices to track people, focusing instead on pets and inanimate objects, such as wallets and keys, that also have a habit of disappearing.

The $29 (£19) device, with a battery life of up to one year, relied on "crowd GPS", he said, relaying signals via other app trackers in the vicinity.

"We have great coverage over the whole world," he said, "But if nobody is nearby, it might not track."

"For that reason we don't advise tracking people - and there are also moral issues."

Mikael Karlsson, of Swedish company Trax, said: "The question pops up in certain countries. Americans never ask about ethics.

"The most important thing, if you want to use a tracker, is to explain why you're using it.

"We have to talk about it. You can tell the kids, 'This gives you more freedom - if I can see where you are I feel safe.'"

Like much of the consumer tech industry, current trackers are hampered by battery size versus lifespan.

"Hardware is shrinking fast, but batteries are going so slowly," said Mr Karlsson.

"Battery is the one thing that stops everything getting smaller."

"Selling fear"

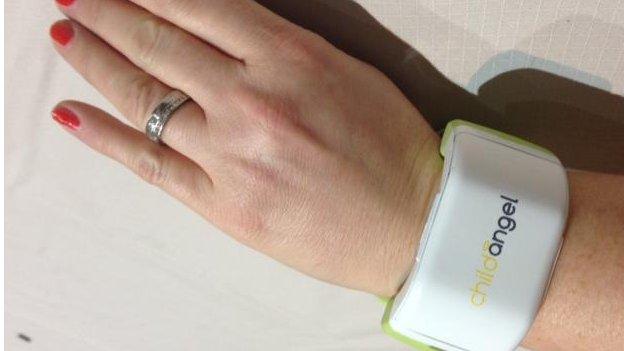

The Child Angel tracker was developed after the founder lost his children in a shopping mall

Child Angel founder Andrew Purcell started researching child trackers after momentarily losing his children in a shopping centre.

"It was only for a few seconds, but my heart stopped, it was horrible," he said.

He spent three years developing his solution, the Child Angel bracelet. Along the way, he received some valuable advice from a competitor.

"He said, 'Get the battery right, and get the signal right,'" he said.

He also conducted some market research among family visitors to British theme parks and received a "phenomenal" response to the idea.

"Over 80% of parents said they would hire it for the day," he said.

Child Angel is a rather chunky bracelet - especially for three-year-olds, the lower end of its target market - but it does have a 48-hour battery life and can send signals via GPS, GSM or wi-fi. If the child tugs at the strap, the parent is alerted via their smartphone.

The $190 (£125) bracelet contains a roaming micro-SIM, which has an additional daily charge of 25 cents (17p).

"We are also looking at the elderly market - we are working on Care Angel and Pet Angel products," Mr Purcell said.

Mr Karlsson decided early on not to adopt the conventional wristband design, opting instead for a small rectangular tablet, which comes with two different clips, and is marketed for both children and pets.

"We had a long discussion when we started development," he said.

"I just thought a wristband was never going to work on a child."

TrackR retails at $249 (£164) and has "one to two days" of battery life.

One unique feature is the "proximity fence", which enables users to draw a circle around their home (or themselves) and then receive notification when their child or pet enters or leaves that domain.

Mr Karlsson is upbeat about the use of the device.

"Some of our competitors sell fear, and that is not what we're selling," he said.

"Everything you can track today will be tracked. You can't stop it, the question is how do you do it?"

Click here for more coverage from the BBC at CES 2015, external

- Published7 January 2015

- Published7 January 2015

- Published6 January 2015