The school growing a digital forest in Rwanda

- Published

What are orchids doing in a school and how is technology helping?

How did pupils at a state school in Somerset end up in discussions with the Rwandan government to build a digital forest? And what role did technology play in making this happen?

Simon Pugh-Jones is a science teacher at Writhlington secondary school in Radstock. The school has a secret that is not shared by any other in the country - it is a world-renowned orchid conservation centre.

Its unusual work has, from inception utilised technology.

"Back in the 1990s we used digital cameras that allowed the children to share their work. Then we started using data loggers to collect data," explained Mr Pugh-Jones.

This allowed them to conduct some breakthrough work, comparing data they gathered on field trips to that in books - it led them to discover that many of the assumptions about orchid conservation were in fact wrong.

Now the school is one of eight in the UK working with Intel to find ways of introducing the internet of things into the curriculum.

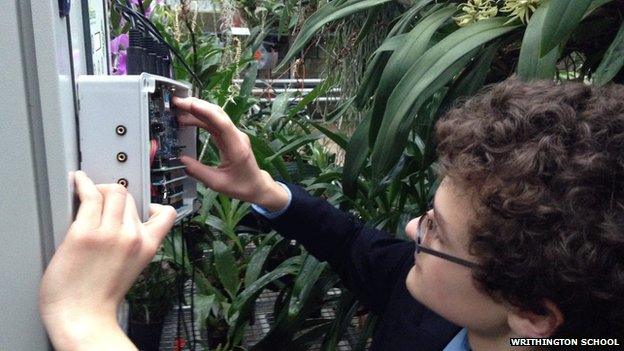

As part of that children are issued with Intel Galileo boards - a rival to the Raspberry Pi - which they can use to build robots, soil sensors or weather stations.

At Writhlington soil sensors are used to help take care of the orchids By embedding sensors in the soil meant that humidity, temperature and other variables could be carefully monitored and data uploaded to the net.

Pupils set up a Galileo board in the school's orchid house

Now the school is in talks with the Rwandan government to set up a digital forest in Nyungwe, Africa's largest mountain rainforest reserve.

It would be a large-scale version of what they do in school.

"The plants would have sensors and the information could be shared with scientists around the world," explained Mr Pugh-Jones.

"It is about making the data accessible and putting a forest in everyone's hands," he added.

For his students back in the UK it can allow them to learn new things and implement them back in the lab.

"Galileo connectivity opens up massive potential and the web-based data will just keep coming. It will make a massive difference to my students, they will be able to interrogate the data via their tablets."

For him technology is playing a huge role in transforming the orchid lab from a school-based experiment to something far bigger.

"It definitely wouldn't be the project that it is without the creative use of technology," he said.

"It can have a big impact on careers. Obviously only a small proportion of my students will end up as plant scientists but the skills they have learned - communication, research, empathy, enterprise, are transferrable," he said.

And it will have an equally big impact on schools in Rwanda who will be asked to design the hardware that will be put into the forests.

The project has proved that education can be revolutionary, he thinks.

"It transforms young people as learners. Nobody leaves Writhlington without the confidence that they can change the world."

Digital future

This resonates with me as an ex-teacher and a mum to a boy just embarking on his secondary education.

So if technology is reviving lessons and offering pupils previously undreamt of opportunities, then surely there is a big argument for schools going even further to embrace the digital future?

My son uses Google docs and a laptop in some lessons but he also still has a lot of heavy text books and photocopied sheets.

His school, like many others, is on the cusp of change - beginning to embrace new technologies but not quite willing to entirely give up the old methods.

So where are the groundbreaking schools that are prepared to make that giant leap into the future?

The school has plenty of laptops which children use from an early age

I put the question to several people at a recent technology in education conference called BETT and was told I needed to visit the Isle of Portland Aldridge Community Academy.

Portland is a place I know well because I grew up there. It is a beautiful peninsula connected to the mainland by the imposing sweep of Chesil beach. It is also an area of deprivation, according to national poverty indexes.

"We have gone back to the drawing board and put 21st century technology at the heart of our curriculum," explained Gary Spracklen, who has the aptly futuristic title of director of change and innovation.

He laughed when I suggested that he is probably the only person working in a school in the UK with this job title.

"In five years time every school will have one," he assured me.

Every child at the academy is issued with an email address when they join the school at three, Chromebooks are distributed free of charge from Year 7 and the school is also piloting a Use Your Own Device scheme with 140 children.

"Because we serve a deprived area we couldn't ask people to bring in a new iPad. Children are bringing in old laptops, old mobiles, £30 tablets. The only thing we ask is that the device has a browser," explained Mr Spracklen.

Children can also bring their own devices

So far about 85 children are bringing their own device to classroom, freeing up more resources for the others and offering them access to reading and maths software, that can set them challenges for the classroom and beyond.

It is also enabling collaborative learning.

"They can take a picture, upload it to the cloud and another child might embed it into a presentation," he said.

To help the collaborative feel of the school the 90 children on the Osprey Quay campus are put in one super-class - with three teachers.

"Instead of three teachers delivering the same information in three different classrooms, they can all take different groups. They are displaying the same collaborative skills that they want the children to use," said Mr Spracklen.

For any school considering putting digital at its heart, a good broadband connection is crucial and Portland, despite being one of the most southerly points of England, has one of the fastest data connections in the country.

The two ten gigabit pipes which serve the island are a legacy from hosting the sailing events at the London summer Olympics in 2012.

It is early days to say whether the school is really breaking the mould but, two terms in, figures for confidence, attitude to learning and attendance are showing a 10 to 20% improvement, according to Mr Spracklen.

Devices alone, whether they be Galileo boards or tablets brought in from home, will not transform the classroom.

Mr Pugh-Jones has some advice for schools thinking of investing in technology.

"I think schools are missing a trick by saying 'here's a load of technology, what can we do with it?' rather than asking what can technology add to what they are already doing."

- Published2 February 2015

- Published22 January 2015

- Published3 December 2014