Lift me higher: Building the world's tallest lift

- Published

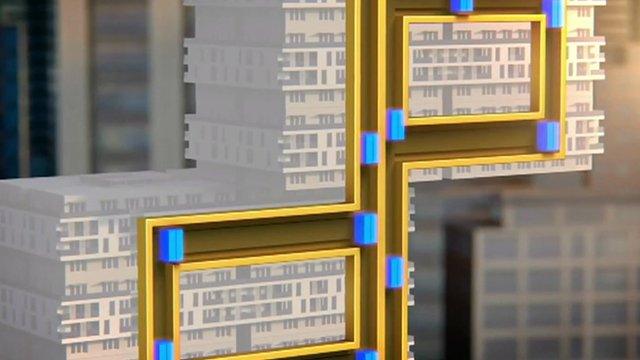

WATCH: How technology will allow lifts to go higher than ever before and even move sideways

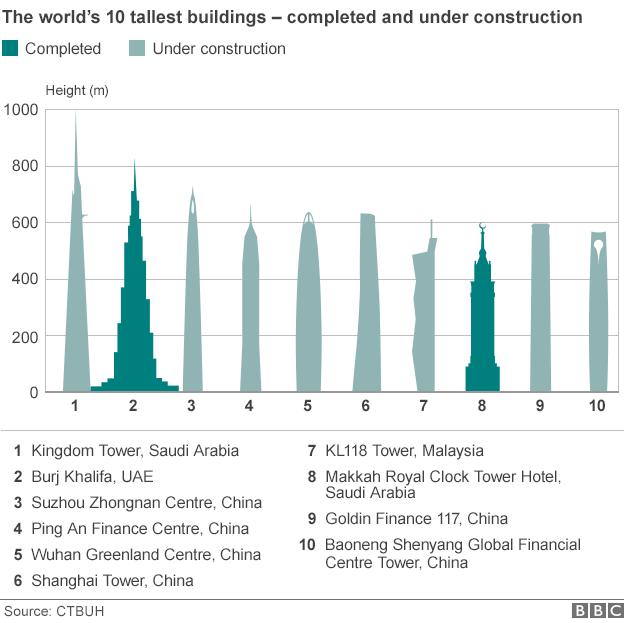

By the end of this decade the records for the world's tallest building and highest lift are going to be broken.

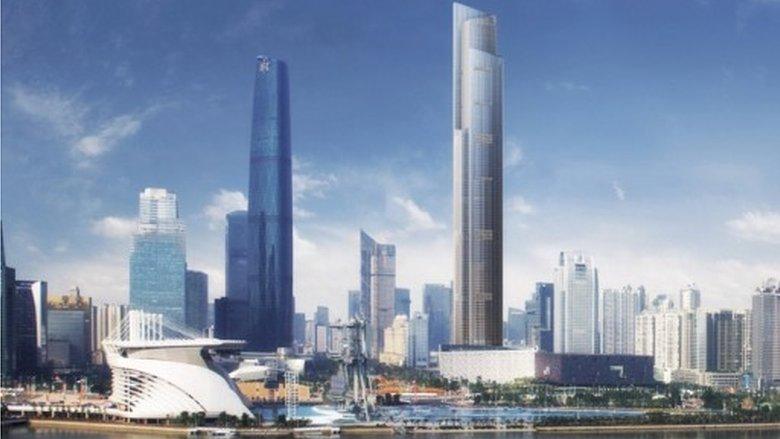

It has been estimated it will cost $1.2bn to build Saudi Arabia's Kingdom Tower

But this is more meaningful than just another skyscraper, in another place, that most of us will never set eyes on.

This could change architecture as we know it.

There are some things most of us just don't think about.

Stepping into a lift and wondering how many floors it could travel may seem too much of a challenge to be worthwhile.

Lift-maker Kone has spent many years considering this problem though.

"While elevators have enabled the rise of city skylines, the technology had reached its height limit," explains its director of high rise technology, Santeri Suoranta.

"Elevators travelling distances of more than 500m [1,640 ft] were not feasible as the weight of the [steel] ropes themselves become so large that more ropes were needed to carry the ropes themselves."

But the company's quest for a solution has borne fruit.

After nine years of rigorous testing, it has released Ultrarope - a material composed of carbon-fibre covered in a friction-proof coating.

It weighs a seventh of the steel cables, so is more energy efficient, has twice the lifespan, and most notably, it makes lifts of up to 1km (0.6 miles) in height a lot easier to build.

Going up

Other lift manufacturers, like Toshiba, Mitsubishi, Otis, Schindler, et al, have been raising their game too.

They've been battling on in the contest to create more eco-friendly, less expensive to run, easier to install, taller and/or faster lifts.

But Kone's creation was chosen to be installed in what's destined to become the world's tallest building.

When completed in 2018, The Kingdom Tower, in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia will stand a full kilometre in height, and will boast the world's tallest lift at 660m (2,165ft).

It will also take the title as the world's fastest double-decker - with one passenger car attached on top of the other - travelling at 10m/sec (32ft/sec).

Longer waits

The Burj Khalifa, which is half a mile high, is currently the world's tallest building.

Its lift reaches 163 floors, and covers a distance of 504 metres. As shown, there's more to designing a lift than seeing how high it can go.

Maintaining the world's tallest building

"There's a science behind traffic design," explains David Cooper from the Institution of Engineering and Technology.

"How many lifts there are in a group, their size and speed."

There are two key measures that engineers must target, he explains:

Kone built an underground test lift shaft in a Finnish limestone mine

Average waiting time - the average amount of time a passenger needs to wait for a lift. This is typically half the interval between one lift departing and another arriving.

Handling capacity - the maximum number of passengers that can be transported in a five minute period, expressed as a percentage of the building's population.

"The average waiting time in a nice office block would be around 25 seconds, with a handling capacity somewhere between 14-17% in a five minute window," Mr Cooper adds.

"So, as much as you can go all the way to the top with a new lightweight lift system, there are still going to be limitations because the number of lifts you need to go back and forth will increase."

Going underground

Right now some of the world's tallest buildings, including London's Shard - which stands a mere 306m in height - have changeover floors where passengers move from one lift to another.

This helps minimise waits.

But taller, express lifts, which only travel between ground level and the higher floors, could still be useful, not least for quick escapes.

Carbon-fibre resonates at a higher frequency than steel, which should mean lifts systems that use it are more reliable. Vibrations caused to tall buildings by the wind are currently a major reason why lifts go out of service.

All very well in theory.

But when neither the building, nor a lift of this height, exists yet, how do you test it?

The use of steel cables puts limits on much of today's elevator tech

Kone believes it has the solution with its Tytyri facility in Finland, external, where it has an lift shaft sunk 333m below ground.

"It is underground, it does not sway, which means we can simulate different sway phenomena in a disturbance free environment," explains Mr Suoranta.

"The other advantage is that underground conditions are very harsh to equipment.

"For example moisture and temperature levels are much more demanding than in normal buildings.

"This means that when components pass our underground tests, they are ready to be taken for use in the world's tallest buildings."

Magnetic lifts

It's estimated that by 2030 there will be 1.4 billion urban dwellers, so with city space at a premium, the only way may be up.

Mr Cooper suggests "magnetic levitation lifts" may offer one solution.

"They are only done horizontally at the moment; there are Maglev trains in Germany," he says.

"They are just held on the track with magnetism, and eventually that will come in a vertical system where there's no contact with the building, it's purely magnetic."

That future may not even be so far away.

Lift maker ThyssenKrupp has been researching and developing what it has named the Multi - a rotating lift system with several cabins looping around one lift shaft.

So, as technology brings a new architectural freedom, it seems only desire, and money will stand between us and the sky.

- Published15 December 2014

- Published22 April 2014

- Published12 November 2013