Cybersecurity: Tackling the threat from within

- Published

Insider thieves are often difficult to spot, because they know the systems and can cover their tracks

For a long time, cybersecurity has been about defending the castle walls against intruders.

The firewalls, anti-virus software, mail-filters and other digital defences used across the business world are generally looking for external threats.

But what if the bad guys are on the inside?

What if your own employees are seeking to defraud your company by diverting cash, copying the customer database, or stealing sales leads?

More than half of all people seeking to defraud a company are inside the fortress, suggest figures from consultancy PWC's Global Crime Report, external.

That figure has risen steadily over the past few years, the firm says, adding that it now seems to be younger staff who are spearheading the trend.

The same survey also saw a change in the nature of fraud. Now, criminals are as likely to indulge in procurement fraud - making false company purchases, for example - as they are to steal cash or data.

Fined billions

"Internal fraud is a huge area," says Laura Hutton of big data specialist SAS, "and it's one that's getting increased focus."

This is perhaps because scandals such as the Libor rate fixing have been exposed in recent years. Banks have been fined billions for their part in fixing rates that underpin trillions of pounds worth of loans and other financial contracts.

Part of the reason internal fraud can be hard to spot is because it tends to be more complex than external threats, said Ms Hutton. By definition, the ones committing the crimes on the inside know the systems and know how to exploit the weaknesses.

The reasons behind an attempt to steal cash or do some rogue trading can also be complex, she says.

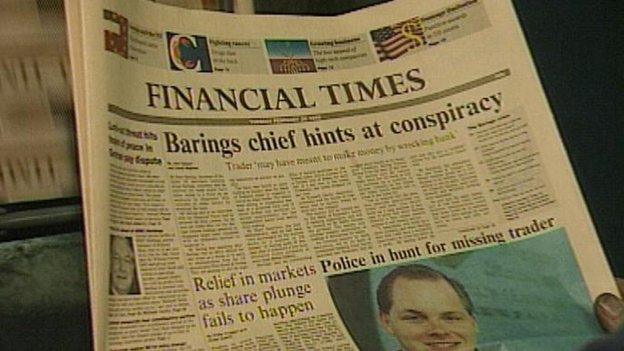

British bank Barings was brought to its knees in 1995 by a rogue trader

"Unauthorised trading sometimes starts because the traders make a mistake that they then try to fix," she says.

If the fix fails, there's an even bigger hole in the accounts that needs filling. Long-established British bank Barings was brought to bankruptcy in 1995 partly through this kind of fraud.

By the end of the saga, trading losses at Barings had ballooned from about £2m to £827m.

Complex networks

The Barings debacle unfolded over a three-year period and often it can take a long time for firms to spot when money or other assets are going missing, says John Yeo from security firm Trustwave.

Part of the reason that fraudsters get away with it for so long is because of the astonishing complexity of the computer networks large banks and other finance houses run these days.

"I do not know of any company that has an accurate asset register of their network," says Mr Yeo. "And they certainly don't have one from a web services or applications perspective, which is a problem an order of magnitude harder to solve."

What that means, he says, is that a lot of activity on a company's network could be going unwatched, opening up an opportunity for anyone keen to pilfer or secrete cash in hidden accounts.

The lack of insight into how many devices are connected to a large corporate network can be staggering, says Dave Palmer, director of technology at networks analysis company Dark Trace.

Large corporations can have highly complex computer systems that are difficult to monitor

It uses sophisticated mathematical techniques to find and map data flows between the PCs, laptops, servers, tablets, smartphones and software on a network. Invariably, he says, the people who run the networks always underestimate how many gadgets are connected.

"One of our first customers thought they had about 5,000 devices on their network because it operated a very strict no Bring-Your-Own-Device policy," says Mr Palmer. "Yet we found 25,000 devices in the first few days of our analysis."

'Formidable job'

That five-fold discrepancy between expected and actual devices is pretty typical, says Mr Palmer, underscoring the lack of control many organisations have over the data swilling around their networks.

Mapping connections between individuals, devices and applications is a formidable job that makes spotting anomalies and fraud all the trickier, he says.

That's not to say the big banks and trading houses are not trying.

Robert Simpson, from data analysis firm Verint, believes financial institutions have tended to throw people at the problem, hence the rise of "compliance officers" tasked with overseeing the deals made by brokers on the trading floors.

Some now employ thousands of compliance officers to keep traders, brokers and dealers honest. These people have the unenviable task of going through the records, usually tape recordings, of the deals being made to spot errors or fraud.

"But they've reached a point where they realise that have hit diminishing returns on hiring people," he says, "so they need to look at how to make these people more effective at what they do.

A lot of activity on company networks goes unwatched

"There's a mountain of data to go through and that mountain just keeps on getting larger."

'Intelligent fraudsters'

They need to do a better job, says Mr Simpson, because deterrence works best when data capture is married with monitoring.

That was shown clearly by analysis of the message logs sent by people involved in the Libor fixing scandal, who got more confident the longer they got away with it, says Mr Simpson.

There's no doubt that spotting this kind of fraud is hard, so financial firms are increasingly turning to big data tools that excel at handling unstructured data, such as the text inside emails, to tackle it.

"It's certainly not an easy problem to solve because you are dealing with very intelligent fraudsters," says SAS's Ms Hutton, adding that failing to spot fraud can have a bigger long-term impact on a company's reputation than on its profits.

In some cases of insider fraud, the amounts of money being stolen are small when compared to the assets most banks have on hand.

But, she points out, to a customer the £50,000 going astray might represent life savings they wanted to leave to their grandchildren.

"You don't want cases like that to happen at all."