How we are becoming nation of digital makers

- Published

WATCH: Two children and one tech reporter attempt to build a robot

In schools up and down the country, children are making apps, building robots and programming Raspberry Pi computers as if their lives depended on it.

And it does not end in class - after-school coding clubs, children's hacking weekends and fairs dedicated to science, technology, engineering and maths (Stem subjects) are popping up everywhere.

Already the internet contributes 8% to the UK's gross domestic product (GDP), but according to Microsoft, one-in-four IT-related jobs went unfilled in 2012.

And the world is changing. Not only will there be far fewer manual and clerical jobs - about 35% of current jobs will be automated over the next 20 years, according to a recent report - but the jobs that are left will require a far higher degree of digital know-how.

The government's answer was to overhaul the way digital skills and computing were taught in schools - a change that happened in September.

Do children need to spend any more time on devices?

Schools have embraced the changes and, despite a shortage of suitably qualified teachers, coding software such as Scratch is now standard in classrooms, while app-building and even 3D printing are becoming commonplace.

Parents used to dragging their teenagers and toddlers away from their tablets might argue children are already immersed in the digital world and do not need any more encouragement to pick up a device.

But while many will indeed be avid consumers, they often do not understand how to manipulate the underlying technology or create it themselves.

WATCH: There are a raft of after-school coding clubs available for children - but what exactly do they do at one?

A recent report from innovation charity Nesta, Young Digital Makers,, external says: "As technology shapes our world, young people need to be able to shape it too.

"As skills and work become increasingly technologically mediated, the need for digital skills is paramount."

Digital making should "become part of the national psyche for the next generation" a key element of youth culture, it says.

More than 80% of the schoolchildren interviewed for the report said they had already made something using digital technology.

A third of the schoolchildren said they had made a robot

What the schoolchildren said they had made using digital technology in the past year:

pictures - 76%

music - 53%

websites - 53%

computer games - 53%

apps - 46%

robots - 34%

3D printing - 31%

And where they had made it:

in class at school - 66%

with friends - 40%

with parents or carers - 27%

in extra-curricular activities or clubs in or after school - 15%

with siblings - 15%

in private classes - 6%

online - 1%

Barclays has just launched Code Playground, offering free monthly sessions in branches around the country, where children and adults can learn coding together.

Mobile operator Vodafone also has a project that aims to get children and parents helping each other to learn more about digital skills and staying safe online, via a web-based quiz and games.

Digital creativity

Meanwhile, the BBC has designated 2015 as the Year of Code.

Barclays runs coding sessions in branches up and down the country

BBC director general Tony Hall wrote in his forward to the Young Digital Makers report that the corporation would give digital creativity a platform "on a scale it's never had before".

"This will enable all audiences to see how Britain has helped shape the digital world, why digital skills matter and their growing importance to our future," he said.

"And we hope it will inspire people - young and old - to take their first steps in moving from digital consumers to digital creators."

Helping children

Coder Dojo, an organisation that runs weekend and after-school coding clubs, has seen a huge surge in interest, but it is finding it difficult to secure venues and volunteers.

The surge in demand was partly "because parents and kids are more aware about coding", said Coder DoJo volunteer Johnny Claffey, but also because the clubs were a less formal way of learning to code - children were encouraged to solve problems among themselves and there was less pressure on them than at school.

Make it Digital initiative

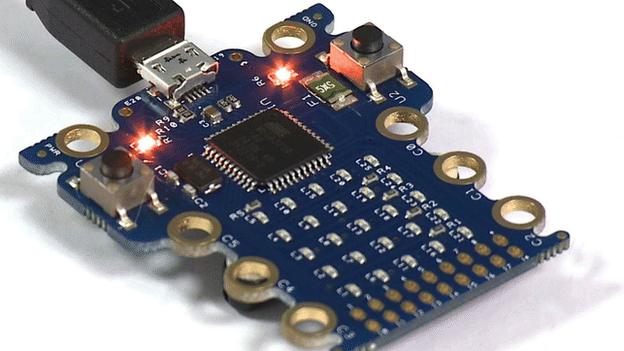

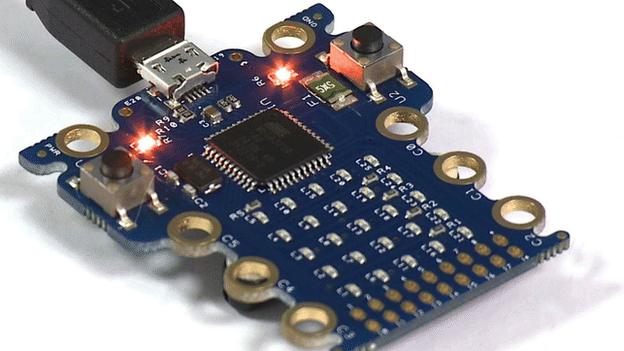

To help kids learn coding skills, the BBC has announced it will be giving away mini-computers to 11-year-olds across the country as part of a wider push to make the UK more digital.

One million Micro Bits - a stripped-down computer similar to a Raspberry Pi - will be given to all pupils starting secondary school in the autumn term.

There have been notable successes in helping children who might feel let down by the traditional educational system:

a severely dyslexic child designed a game in Scratch to help children recognise letters and sentences

a child who struggled with numeracy created a similar one about number bonds

a child who had been excluded for disruptive behaviour found a talent for coding that gave him the confidence to go back to school.

"He designed a game and went back into his school one Monday morning, asking if he could do a show-and-tell about the game he designed," said Mr Claffey.

"He is now back at school and much more focused."

Last year coding clubs such as those run by Coder Dojo allowed 130,800 children to get involved in digital making - but this is far too few, according to the report.

"These organisations are doing a terrific job but their impact is currently limited," it says.

- Published12 March 2015

- Published12 March 2015

- Published26 February 2015

- Published30 September 2014

- Published17 February 2015