Intelligent machines: Will we accept robot revolution?

- Published

Who is most at risk: the humans or the machines?

Would you share your home with a robot or work side by side with one? People are starting to do both, which has put the relationship we have with them under the spotlight and exposed both our love and fear of the machines that are increasingly becoming a crucial part of our lives.

In Japan they grow so attached to their robot dogs that they hold funerals for them when they "die".

Sony, the firm that began making the popular Aibo toys in 1999, decided to stop offering repairs in 2014, meaning once they broke down they were fit only for the scrapheap.

But people weren't willing to throw them in the rubbish bin, wanting instead to say goodbye to them in the same way you would to a human or pet.

In Japan robot dogs are treated like pets and mourned when they die

Growing irrationally attached to machines is a common human trait as Kate Darling, from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology's Media Lab, found out when she started a workshop asking people to torture the loveable robotic dinosaur toy Pleo.

"People wouldn't do it. We had to threaten that we'd destroy the dinosaurs if they didn't," she said.

She isn't a sadist - the workshop was an experiment to try and unpick why it is that people grow so attached to a machine.

In the last year she has conducted more such experiments in the lab, asking people to hit robots with mallets and finding similar resistance.

So why do people find it so difficult to be mean to a machine?

"We have a natural tendency to anthropomorphise everything and we are hardwired to respond to lifelike movement. We project intent on to it and social robots that mimic our movements, sounds, we subconsciously associate with emotions and feelings," Ms Darling told the BBC.

Cute robots

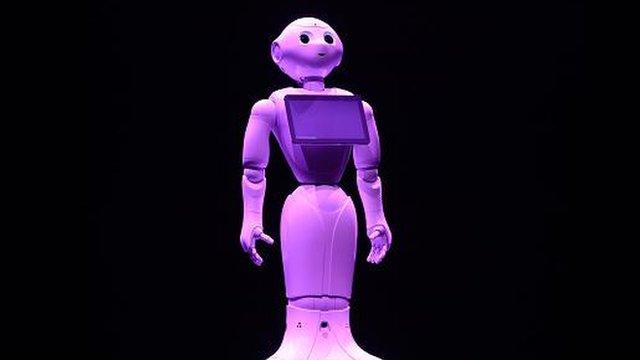

Pepper was created not just to appeal physically but also to respond to emotions

It is a trait that those in the robotics industry are keen to exploit and much of the focus of mass-market robots is on making them as cute and non-threatening as possible.

Humanoid robots are everywhere. Go along to a robot convention and even the most machine-like bots will be wearing T-shirts or have makeshift faces in order to make them more sympathetic.

Pepper, a robotic companion that recently went on sale in Japan, is the ultimate in cute-looking robots.

It is also hardwired to understand human emotions.

In order to allow it to decode emotions, Pepper is played a video of someone speaking nonsense first angrily and then happily so that it will recognise the different voice patterns.

Vincent Clerc, who led the project to design Pepper, told a recent conference in Grenoble: "We want people to be emotionally connected and involved with robots. We don't want a robot to be a simple machine like a vacuum cleaner. If you are tired, you look tired. And you want a robot that recognises when you look tired."

Gender worries

Does a robot need breasts?

Making robots more human-like often means assigning them a gender and this could be creating the next big battlefield in the industry, thinks Prof Kathleen Richardson, a robot ethicist from De Montfort University in Leicester.

"Male robots tend to be explorer robots or war robots whereas female robots are attractive and play roles in the service industry as receptionists or waitresses," she said.

"Ask the scientists behind them why they have assigned a particular gender and they will say there was no deliberate intent but that is not true, it is not innocent. It is a decision taken with their own experience of the world."

Ms Darling is similarly frustrated by the gender stereotypes in robotics and AI (artificial intelligence).

A recent visit to Austin, Texas to see IBM's cognitive AI platform Watson - named after the male first chief executive of IBM - left her angry.

"There was a second AI in the room. It just turned on the lights and greeted visitors and it had a female voice - it drove me crazy," she said.

Those who create robots need to think much more about the gender and look of the robots they are designing in order not to "further entrench current stereotypes", she said.

Fictional robots

HitchBOT was smashed to pieces on a hike around the US

The concept of a thinking machine has been around for thousands of years and is something humans seem obsessed with - from the Greek myth of Pygmalion, a statue brought to life, through to the automata of Victorian society, we have long dreamed of putting human characteristics into machines.

And when we do - in books, films and TV shows - the machines usually turn bad. From Hal in 2001: A Space Odyssey to 2015 film Ex Machina, we clearly have little trust that machines will be loyal to us.

So why do we fictionalise robots in our own image and then have them betray us?

Jodi Forlizzi, from the US Human-Computer Interaction Institute, puts it down to human nature.

"I think we create narratives and stories about everything in the world: people, robots, spirits, zombies, etcetera that set us in opposition to them," she told the BBC.

When hitchhiking robot hitchBOT set out on a journey across America to test our relationship with machines, it quickly found out how mean humans can be.

Its trip ended abruptly in Philadelphia where it was smashed to pieces. Either an example of the human tendency to destroy what it doesn't understand or mindless vandalism, depending on your point of view.

Its creators posted after its demise that "its love for humans will never fade" but can we ever reciprocate this loyalty?

Can we learn to love our robot companions?

Ryan Cato, professor of law at the University of Washington, thinks that we will accept robots into our homes, offices and cars because their usefulness will outweigh any doubts we have about them

Whether society can draw up rules for how we treat them is less clear, he thinks.

"These robots feel like people to us and there is nothing in law to deal with that relationship between a human and a thing. We are in a weird netherworld," he said.

Ultimately it could be humans that lose out, he warns.

"These devices may make our lives better but they are also always passively listening to you and they have a physiological presence.

"They will be in our cars, in our homes and you will never feel alone which is never a good thing, either psychologically or spiritually."

- Published3 August 2015

- Published27 August 2013