Intelligent Machines: New York's super smart AI couple

- Published

If you thought that wandering round a party trying to "network" with people was awkward, try making small talk with a machine. I recently went to New York to meet two - a virtual assistant dubbed Amelia owned by IPsoft and the IBM-owned cognitive platform Watson.

First problem - you aren't sure what questions you can ask and what you can't. These machines are not yet ready for general chit-chat. They are only as good as the data that they have ingested.

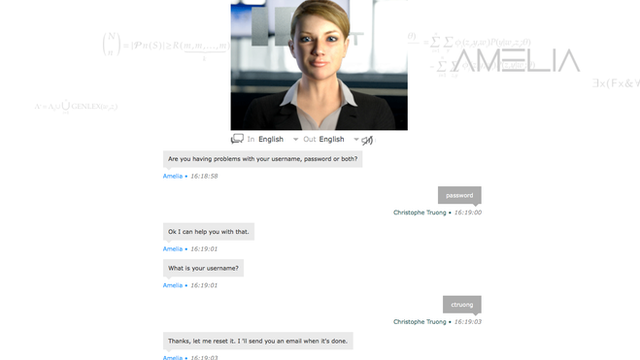

Amelia is the embodiment of smart efficiency - her on-screen avatar projecting the image of an ambitious and business-like young woman.

Listen: Jane Wakefield has been to New York to meet the "power couple of Artificial Intelligence", IBM's Watson and IPsoft's Amelia

I start with small talk and ask her, perhaps stupidly, how she is. It doesn't compute. I ask her where she lives.

"Right in front of you", she replies.

OK that is logical but not exactly chatty so I try a new tack - asking her what she can talk about. It turns out that there is a wide range of conversation avenues she wants to go down - from how to install fire and smoke alarms, to help with my mortgage.

Amelia is being used in a wide variety of industries - she is a cosmetic adviser for one of the largest retailers in Japan, a financial adviser for a large New York-based investment house and a vendor manager for oil and gas contractor Baker Hughes.

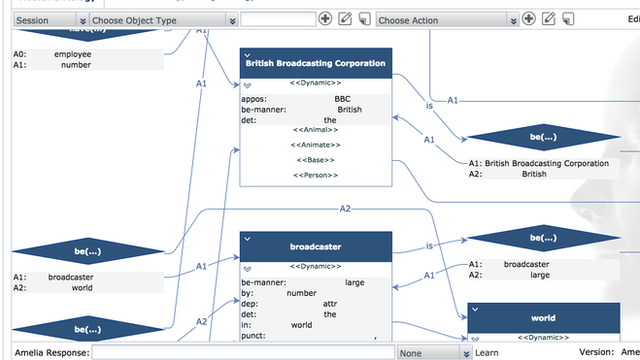

A glimpse into Amelia's 'brain' as she tries to understand what the BBC is

She is the result of 17 years worth of work from her charismatic and enthusiastic creator Chetan Dube and his team of scientists from fields as diverse as computational linguistics, semantic networks, spread activation and affective computing.

Prof Dube began thinking about such a creation when he was assistant professor of mathematics at New York University.

Seventeen years later he believes we are at the breakthrough moment for AI - which will, he predicts, become "the megatrend of the 21st Century".

Already there are plenty of virtual assistants available on the web, like furniture store Ikea's Anna, who is designed to help you around the website.

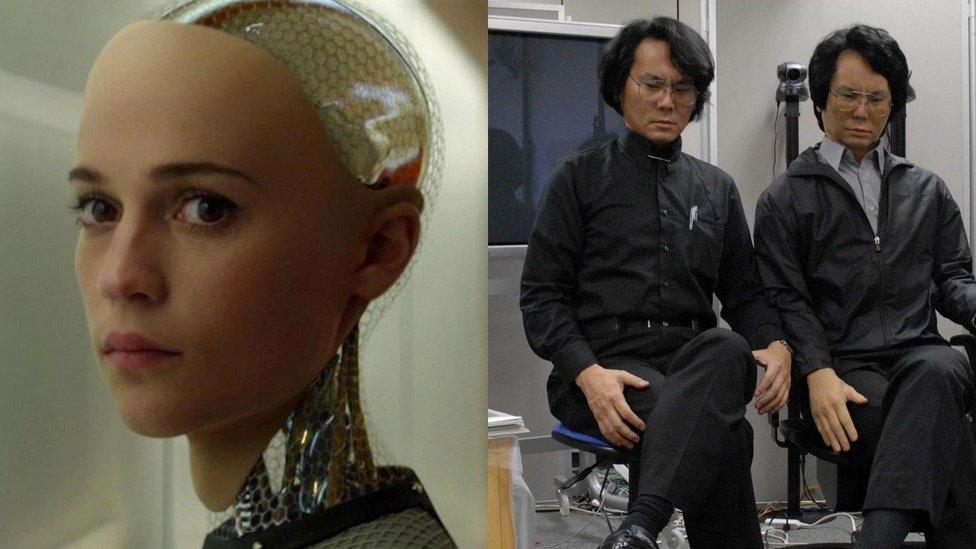

Is this intern human or machine? In the next decade we might not be able to tell the difference, says Prof Dube

But ask Anna to go outside of her comfort zone and answer a question about something other than soft furnishing, and she gets dumb pretty quickly.

Amelia is different, according to Prof Dube, because she has been developed by studying how the human brain processes information.

"We study how neural mind maps work. Not just the syntax of what is said but the semantics of what is said," he tells the BBC.

So peek behind the avatar into her "brain" and you will see that it emulates neural behaviour - she builds a mind map of the questions, and looks not just at how sentences are constructed but the deeper meaning behind them.

Prof Dube likens her to "a Mensa kid intern".

Although perhaps unlike her human equivalent she has no problem admitting if she doesn't understand a question. She will pass the person asking on to a human helper, listen in and then deconstruct how the problem was solved so she can do it herself the next time around.

And she learns pretty quickly - when she began work as a digital service desk engineer at a media company, she could deal with just 32% of the queries in the first month but by the end of the third month she was able to deal with more than 60%, according to Prof Dube.

Prof Dube has huge ambitions for Amelia and sees her going far further than most experts would dare to suggest - providing the brains behind a walking, talking AI within the next 10 years as robotics mature and offer very more realistic "bodies" for sofware brains such as Amelia.

"I have the firm conviction that within this decade we will be able to pass someone in the corridor and not know if they are human or Android," he said.

I've met a few robots and they seem to fall over a lot so I'm not convinced we are yet ready for talking, walking AIs.

It was difficult to assess the performance of Amelia because the topics she knew about were not really ones I wanted to know about, although she did offer the potential for more human-like chat.

Elementary, dear Watson

My second AI encounter is with Watson, IBM's so-called cognitive platform named after the firm's first chief executive Thomas J Watson.

It is a very different beast to Amelia.

As Prof Dube puts it: "Amelia does things that humans can do and Watson does things that people can't do."

I'm slightly surprised to find out that there are several versions of it.

Meeting Watson feels a bit like meeting a celebrity - albeit one with a bigger brain than most

First I get to meet the celebrity "old" Watson - the large cube of server boxes that famously won the Jeopardy quiz show back in 2011- now stored at IBM Watson's research lab just outside New York.

The new smaller Watson - just four boxes high - has moved from the leafy suburbs to the heart of New York City at IBM's recently opened and snazzy Watson centre.

Such a move is perhaps apt as IBM tries to reinvent Watson as a business partner in a range of industries.

The firm is betting a lot of its future on its new slimline Watson and what it calls cognitive platforms. Its view is that we, as humans, are overwhelmed by data and increasingly need machines to help us sort through it.

As Guru Banavar, head of research at IBM, explains: "We call Watson a cognitive computing system because we fundamentally think these kind of systems will augment human cognition. It is designed to do things that are difficult for humans to do."

Watson is designed to help humans cope with data overload

He envisions a scenario where Watson - which in reality is just software which operates in the cloud - is available "for every professional on the planet", changing the "way the world works".

The platform is already in demand. It is being used by cancer specialists in a dozen or so hospitals to help wade through vast amounts of medical data and help come up with treatments for individual patients.

It has been used in Kenya to help find preventions for cervical cancer and has recently started working on spotting early stage skin cancer, via sophisticated visual recognition software developed at IBM's research lab.

Meanwhile financial software start-up Vantage uses Watson to help make investment decisions.

"I thought at first that we'd build a machine that would tell us when to buy and sell but it is not like that at all," says chief executive Greg Woolf.

"I identify the things I am looking for and ask the computer to go and get it. I am directing the computer which will bring data back in an easy to understand format that I can make a decision on.

"I take the decision. The computer does the grunt work."

Meaning of happiness

When I meet Watson there is a new application being tried out - some 2,000 talks from the TED (Technology, Entertainment and Design) conference have been loaded into the system and Watson can sift through them to provide users with short versions of relevant talks.

I start with the question we'd all like answered "What is the key to happiness?" but this throws up no results.

I'm told to refine my question and make it more about the relationship with something else so I ask: "What is the relationship between happiness and money?".

I get a few talks thrown at me - none of them entirely answering the question.

It is a slightly disappointing encounter with what I'd hoped would be the biggest brain on the planet.

Both Amelia and Watson are still learning and, at the moment, they are still only able to respond to very specific enquiries. General chat seems a long way off.

The AIs I met in New York illustrate both how far we have come in the world of artificial intelligence and how far we still have to go.

- Published11 September 2015

- Published6 May 2015

- Published9 October 2014