Step inside the secret robot house

- Published

Zoe Kleinman's night in the robot house

In a leafy cul-de-sac in the Home Counties sits an ordinary semi with some extraordinary inhabitants.

Hertfordshire University robotics professor Kerstin Dautenhahn purchased the house in Hatfield 10 years ago in order to observe how ordinary people get along with machines in everyday life.

Robot vacuums, dogs and simplistic humanoid children are all regular visitors.

It is frequently home to two prototype "care robots" - Care-O-Bot, who looks like a 440lb (200kg) mobile phone in a Tuxedo, and Sunflower, a splendid homage to '70s sci-fi.

They are designed to fetch and carry, attract attention and monitor their human housemates for signs of pre-programmed unusual activity.

While local residents are aware of their cyber-neighbours, the exact location of the house is kept secret for security reasons.

"When we first started investigating robots as home companions we had a proper lab, but we realised people felt very uncomfortable," Prof Dautenhahn told the BBC.

"They felt observed and studied... so, we moved into a more realistic environment where people feel more at home."

Plug sensors monitor activity in the kitchen.

It's not exactly home from home - the house is kitted out with more than 60 sensors, which the robots can be programmed to respond to.

There are big cushion-like sensors on the sofas and chairs and beds, so the robots know where their human is resting, and much smaller devices on the cupboards and doors, light switches, taps and even on the toilet seat.

An old Xbox Kinect sensor keeps watch in the kitchen and small round surveillance cameras are installed in the living room ceiling. There are further Xbox controllers on the table, not for a quick game of Fifa, but to manually control the robots if need be.

"We try to use as much existing technology as we can," said senior research fellow Dr Joe Saunders.

"It's very expensive to develop new technology, especially if it exists already."

Invited to spend the night, I found the sensors - generally discreet as they were - extremely unnerving. The constant hum of computers was eerie too.

It felt like the house was watching me - and it was.

The next day I was presented with a chart detailing exactly when and where I had moved, how restless I'd been in my sleep and even, to my embarrassment, when I went to the loo.

The robot house did not miss a thing.

"Initially people are concerned," said Prof Dautenhahn.

"But if you point out the benefits - if the house notices someone gets up and goes to the bathroom and doesn't return for an hour to bed it's probably a [bad] situation which might have happened - if you outline that most people are very positive,"

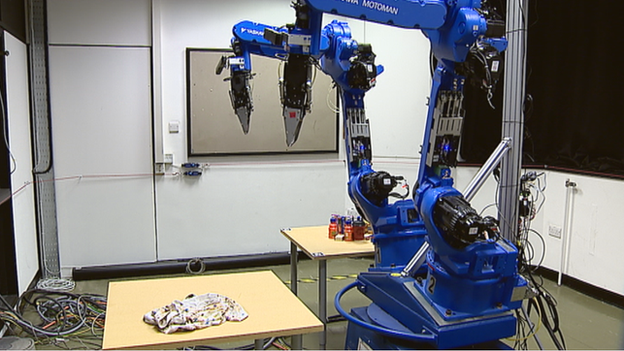

Fancy a cup of tea with this?

or this?

And how about the risk of a rogue robot deciding to have a midnight feast on a BBC journalist?

"It's very unlikely - simply because the robot is very sensitive," said Dr Saunders.

"If you go within 10cm [4in] of it, it will shut down completely and it has various other sensors, so it knows how to avoid you and not to come too close."

The university has also invested in researching robots designed to interact with children with special needs.

Kaspar has proved extremely popular with children with autism, external, even among those who have a tendency to shun human interaction almost entirely.

Two Kaspars and their "parent" Dr Ben Robbins

To adults his simplified features and slow gestures may seem a little creepy.

"Children with autism, the moment they see [Kaspar], 99.9% of them run to it hug it, kiss it, interact with it," said Dr Ben Robbins who works with the machines.

"To them, they feel safe. It has human features but it is still very robotic - it is not pretending to be a person."

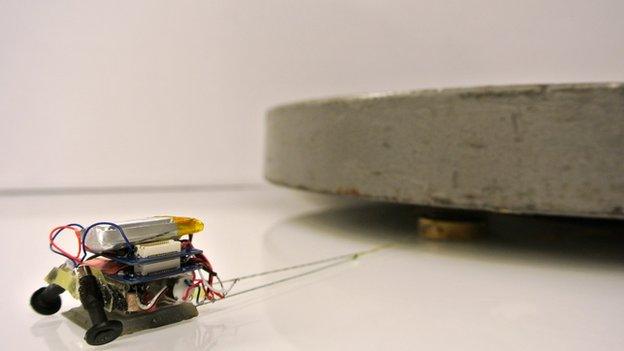

Battery life is a perennial thorn in the side of artificial intelligence.

Large robots, like Care-O-Bot, have a lifespan between charges of about two hours.

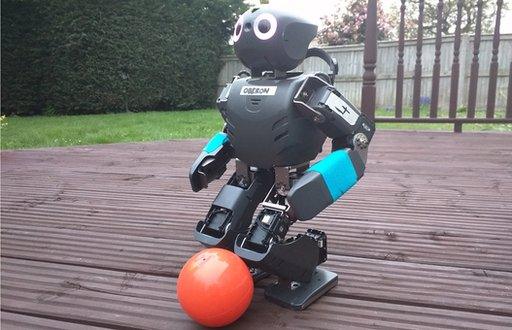

But small, highly active machines like Oberon - a member of the university's robot football team Boldhearts, who showed off his ball skills in the garden - have just 10 minutes of power at a time.

Oberon and the Boldhearts will be competing at the Robot World Cup in China this summer.

Another challenge that continues to stretch the robotics community is autonomy.

"There's a strange paradox in AI (artificial intelligence)- things that are easy for people to do are hard for robots and things which are easy for robots are hard for people," said Joe Saunders.

"Our robots are about 80% autonomous now - the other 20% may take five or 10 years."

With robot vacuum cleaners and even lawn mowers already becoming more mainstream, will this street and many others be full of robot houses in the next decade?

"It's very difficult to put a timeline on it," said Prof Dautenhahn.

"We will see more and more technology that assists people in their homes - but it will probably be 20 years or longer for multi-purpose robots.

"It's still very hard to put it all together into one system."

- Published12 May 2015

- Published28 April 2015

- Published7 May 2015