L'Oreal to start 3D-printing skin

- Published

Could cosmetics be tested on 3D-printed skin in future?

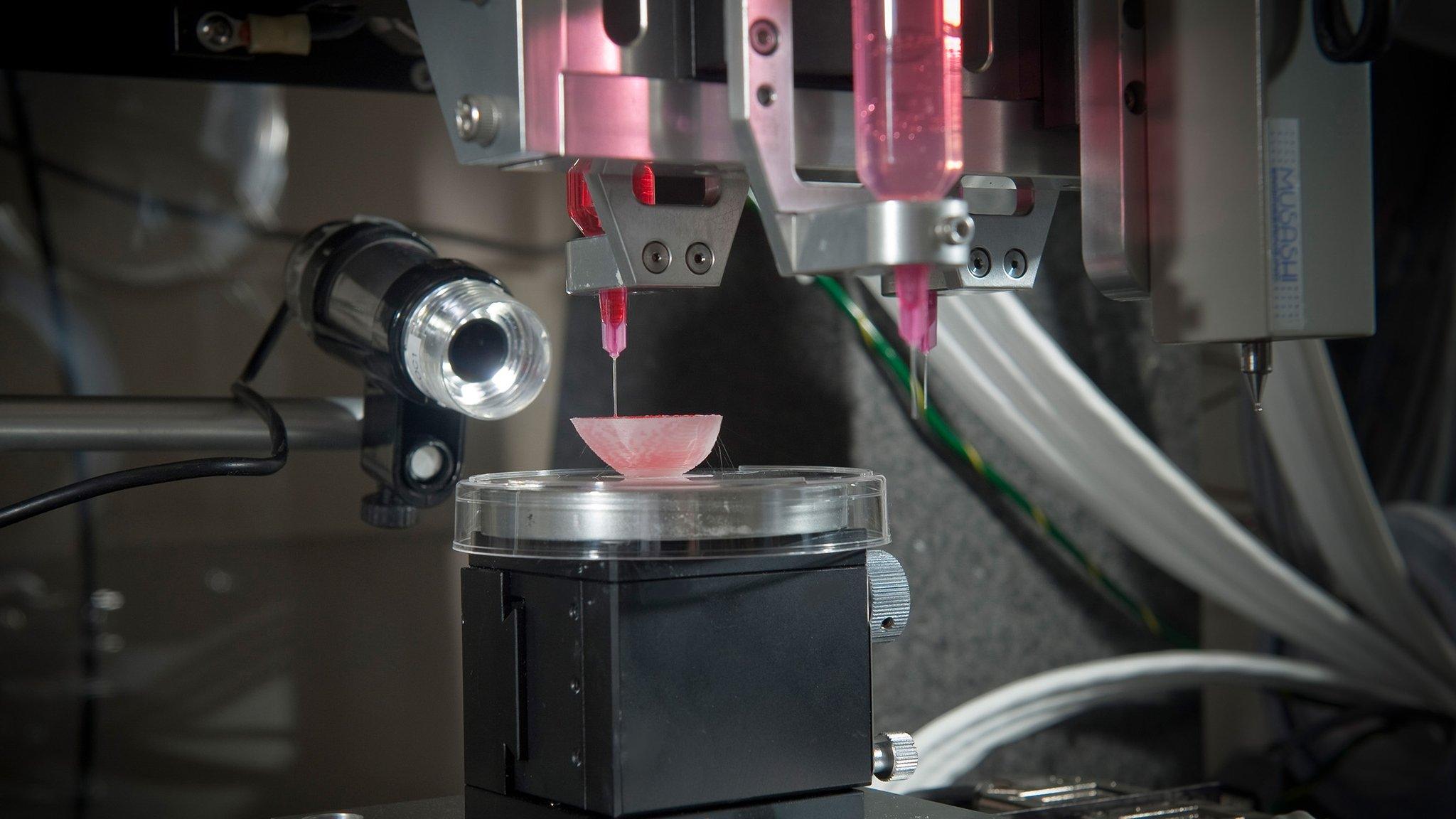

French cosmetics firm L'Oreal is teaming up with bio-engineering start-up Organovo to 3D-print human skin.

It said the printed skin would be used in product tests.

Organovo has already made headlines with claims that it can 3D-print a human liver but this is its first tie-up with the cosmetics industry.

Experts said the science might be legitimate but questioned why a beauty firm would want to print skin.

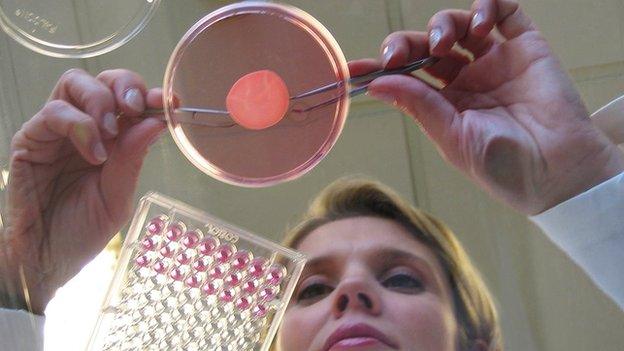

L'Oreal currently grows skin samples from tissues donated by plastic surgery patients. It produces more than 100,000, 0.5 sq cm skin samples per year and grows nine varieties across all ages and ethnicities.

Its statement explaining the advantage of printing skin, offered little detail: "Our partnership will not only bring about new advanced in vitro methods for evaluating product safety and performance, but the potential for where this new field of technology and research can take us is boundless."

L'Oreal already grows skin in its labs

It also gave no timeframe for when printed samples would be available, saying it was in "early stage research".

Experts were divided about the plans.

"I think the science behind it - using 3D printing methods with human cells - sounds plausible," said Adam Friedmann, a consultant dermatologist at the Harley Street dermatology clinic.

"I can understand why you would do it for severe burns or trauma but I have no idea what the cosmetic industry will do with it," he added.

3D-printed livers

The Wake Forest Institute for Regenerative Medicine has pioneered the field of laboratory-grown and printed organs.

It prints human cells in hydrogel-based scaffolds. The lab-engineered organs are placed on a 2in (5cm) chip and linked together with a blood substitute which keeps the cells alive.

Organovo uses a slightly different method, which allows for the direct assembly of 3D tissues without the need for a scaffold.

It is one of the first companies to offer commercially available 3D-printed human organs.

Last year, it announced that its 3D-printed liver tissue was commercially available, although some experts were cautious about what it had achieved.

"It was unclear how liver-like the liver structures were," said Alan Faulkner-Jones, a bioengineering research scientist at Heriot Watt university.

Printing skin could be a different proposition, he thinks.

"Skin is quite easy to print because it is a layered structure," he told the BBC.

"The advantages for the cosmetics industry would be that it doesn't have to test products on animals and will get a better response from human skin."

But printed skin has more value in a medical scenario, he thinks.

"It would be a great thing to have stores of spare skins for burn victims."

- Published2 July 2012

- Published17 September 2013