Google Play revamps its Android apps' age ratings

- Published

Google is passing over control of app ratings in its Play store to an independent organisation

Later this week, Google Play will revamp the way it rates apps.

The Android store will abandon the low/medium/high maturity classifications it has used until now and switch to a system run by an outside body.

As increasing numbers of youngsters are left alone to play with smartphones and tablets, the move will allow Google to show it takes its responsibilities seriously.

But there remains the potential for confusion - and controversy.

So why make the change?

Google says it wants to reassure parents that apps are properly labelled by bringing in the experts rather than relying on developers to self-certify their products, as had been the case until now.

Rather than use its own proprietary classifications, it will offer parents and children labels similar to those already used to provide guidance about the suitability of boxed video games for different age groups, which should be relatively familiar.

The web and mobile versions of Play will get the new ratings first, with the Android TV app store to follow

Who is being put in charge of rating the apps?

A relatively new body called the International Age Rating Coalition.

It was founded two years ago, but its members have been in the age classification business for decades.

Instead of a centralised office issuing a single global age rating for each app, Iarc's five participants each give their own grades, taking into account local laws and different cultural sensitivities.

So, apps that contain nudity, violence, references to gambling and drugs and other potentially unsuitable material, will be ranked differently depending on where in the world a user's account is based.

The bodies involved are:

The Australian Classification Board

Classifcacao Indicativa, which covers Brazil

The Entertainment Software Rating Board (ESRB), which looks after North America

Pan European Game Information (Pegi), which is used by the UK and 29 other European countries

Unterhaltungssoftware Selbstkontrolle, which is specific to Germany

Generic ratings are assigned, external to territories without a participating authority.

If, for whatever reason, one or more of the rating authorities refuse to classify an app, it will not be distributed in the relevant countries.

Iarc's members already rate all the apps submitted to Mozilla's Firefox marketplace

That sounds like it could be a rather time-consuming process for developers.

Iarc says not.

Developers only have to fill in a single questionnaire about how their apps function and the content they contain.

The different bodies then share the information.

Makers of apps that don't contain content of their own - including calendars, calculators and other utilities - should be able to complete the process in less than a minute, the coalition's chairwoman Patricia Vance told the BBC. Even those involving more work shouldn't take longer than 15 minutes.

Google and the other app store owners adopting Iarc's ratings will cover its costs

The system is automated, so the ratings should be spat out shortly after the answers are punched in.

However, Iarc promises there will be manual checks of the most popular apps and any which receive complaints from customers.

"The volume of apps in a storefront like Google Play is just enormous," explained Pegi's Dirk Bosmans.

"We can't follow the same [hands-on] approach that we do for boxed games, but we don't have to make the process as robust as there's no physical product here.

"If a physical product is mis-rated that's a logistical nightmare as you have to pull the boxes back from the shops and reprint them.

"With apps you can just say, 'That age seven rating should have been a 12,' and with a snap of the finger, reprogramme it."

Existing Android apps will have to be submitted to Iarc's scheme the next time an update is submitted

Why aren't other app stores doing the same?

Actually, Google Play isn't the first to throw its lot in with Iarc.

Mozilla's lesser-used Firefox Marketplace already depends on its rankings.

And the body says Microsoft, Sony and Nintendo are also set to join.

Microsoft's Windows Phone store currently only has age ratings for video games

What about Apple?

Iarc would love to take over the iOS store's age ratings and says it has discussed the possibility with the iPhone-maker.

But for now, Apple has opted to retain its own system.

That could potentially be confusing for families using a mix of devices.

For example, Apple's guidelines state that an app depicting mild occurrences of cartoon-like violence should get a nine+ rating, but the ESRB allows the same type of product to be classed E, meaning suitable for everyone.

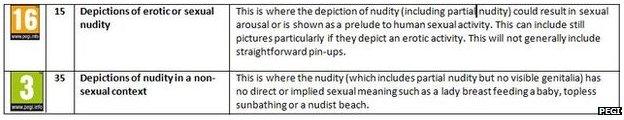

Pegi's rating scheme is less restrictive concerning the use of nudity than Apple's

Likewise, Apple says apps including nudity should be limited to a 17+ audience, while Pegi says nudity is fine for the 3+ crowd if it's non-sexual and 16+ if erotic.

Apple declined to comment about its future plans.

Assuming parents don't disagree with Iarc's grades, can they now trust them to protect their kids?

Not quite.

The ratings are limited to an app's content and don't involve privacy issues.

So, Iarc's members would judge a storybook app, for instance, to be suitable for a pre-teen age group based solely on the innocuous plot it tells.

But it could still be problematic if it required the user to share data about their location, contacts, photos or other device use.

ESRB's icons reflect whether an app is sharing data even if that does not affect the age score it receives

This is a real concern. Earlier this month, 29 privacy watchdogs across the globe announced they were investigating what information was being collected by some of the leading apps targeted at children because of fears that too much personal information was being recorded.

Apps containing user generated content that isn't moderated before publication pose a separate challenge.

The ESRB plans to give such products a "teen" rating, while Pegi will instead show an exclamation mark icon, indicating that further parental guidance is necessary.

Apple currently rates Facebook as 4+ despite the social network requiring members to be at least 13, because the classification is based on the app's content rather than its privacy requirements

Isn't there a risk that children will just ignore the age limits and download what they want?

Yes. But there are proposals to change this.

Some campaigners are pressing for an age-verification scheme that would let app stores confirm that young device-owners were old enough to download a product without needing to hold personal information about them on file.

This would involve a trusted third party carrying out the necessary ID checks and then vouching for the child's age at the point of purchase, explains Dr Rachel O'Connell, chief executive of the tech advisory service Trust Elevate.

If the child was flagged as being below Iarc's relevant age rating, she said, an email could be automatically sent to their parents asking for their permission.

While it might take years to get such an initiative up and running, the GSMA - which represents mobile operators - says other steps could be taken in the meantime.

Parents can buy software that gives them more control over what apps their children can launch and download

It suggests age-restricted apps could pose children a series of challenging questions to try to catch out those attempting to pretend to be older than they are - such as requiring them to type in their date of birth - and only giving them one chance to get the answer right.

There are also existing parental control apps, external and settings in Android Lollipop that can be, external used to prevent unauthorised access to the marketplace and only allow children access to specific titles.

- Published22 May 2015

- Published19 May 2015

- Published15 January 2014