Does the government really want to ban WhatsApp, iMessage and Skype?

- Published

- comments

Eight hundred million people around the world use WhatsApp to communicate, we learned this week from its owners, Facebook.

Yet this is the messaging service which could soon be banned by the British government because its use of encryption makes it too private for the security services to access. That at least was the story repeated in several newspapers in recent weeks, external, and frequently denied by Downing Street.

But this morning even the Financial Times seemed to back it up. In an article about the battle between governments and corporations over access to encrypted messages it says this: "David Cameron, UK prime minister, has proposed a complete ban on strong encryption 'to ensure that terrorists do not have a safe space in which to communicate'."

WhatsApp is just one of the services that uses strong encryption for their messages, along with Apple's iMessage and Skype's internet calls. Both the US and UK governments have expressed growing concerns that criminals and terrorists are making use of such services to communicate, knowing that they are completely private.

So does the prime minister really want to ban them? The idea first arose in a speech he made in January which posed this rhetorical question: "In our country, do we want to allow a means of communication between people which even in extremis, with a signed warrant from the Home Secretary personally, that we cannot read?" His answer was no.

That was seen as a clear signal that the government would demand that corporations like Facebook, Apple and Microsoft - which owns Skype - should either provide a backdoor to their encryption or stop using it completely. The government insisted that this was an over-interpretation of his remarks, and everything went quiet for a while.

Then after the election it became clear that a new and comprehensive communications data bill would clarify and extend the access of the police and security services to data held by the internet companies. That brought more speculation about a ban on end to end encryption.

That was reinforced when in a response to a question from a Conservative MP, the prime minister used a very similar form of words to those in his January speech: "We must look at all the new media being produced and ensure that, in every case, we are able, in extremis and on the signature of a warrant, to get to the bottom of what is going on."

But take a look at how WhatsApp, Skype, and iMessage work and it seems clear that no warrant would allow government agents "to get to the bottom of what is going on" in their messages.

Here, for instance, is what Apple's privacy policy tells users about its iMessage and FaceTime services:

"Apple has no way to decrypt iMessage and FaceTime data when it's in transit between devices. So unlike other companies' messaging services, Apple doesn't scan your communications, and we wouldn't be able to comply with a wiretap order even if we wanted to."

Technology company leaders, including Apple's Tim Cook and Facebook's Mark Zuckerberg, have warned that any attempt to tamper with encryption will only help criminals and threaten the security of consumers who depend on it for services like online banking.

It is hard to imagine that any of these American giants would submit and provide a different level of service to UK customers from that on offer elsewhere. Microsoft gave me this statement when I asked about the encryption of Skype conversations: "Advanced encryption is an important part of our security strategy for Skype now and in the future." So, a mighty battle is in the offing.

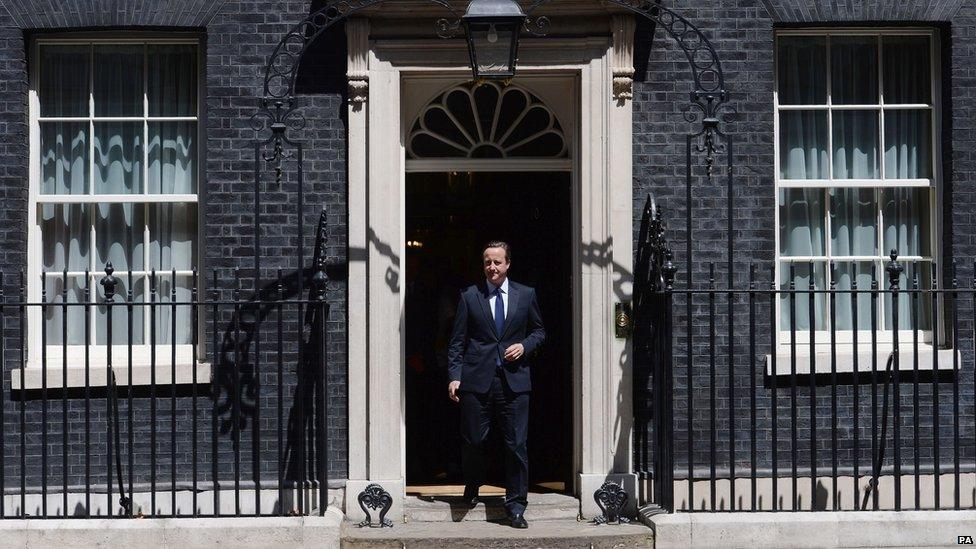

Is No 10 ready for a "mighty battle" with US tech giants over encryption?

Or is it? I called Downing Street again this morning to check on the latest line on encryption. I was informed that no, of course the prime minister didn't want to ban encryption, he just wanted to make sure there was no safe space for terrorists. I suggested those two statements were incompatible, and I was told they would come back with further illumination.

A couple of hours later Downing Street sent me this statement:

"We recognise the importance of encryption: it keeps people's personal data and intellectual property secure and ensures safe online commerce.

"But clearly as technology evolves at an ever increasing rate, it is only right that we make sure we keep up to keep our citizens safe. There shouldn't be a guaranteed safe space for terrorists, criminals and paedophiles to operate beyond the reach of law.

"The Government is clear we need to find a way to work with industry as technology develops to ensure that, with clear oversight and a robust legal framework, the police and intelligence agencies can access the content of communications of terrorists and criminals in order to resolve police investigations and prevent criminal acts."

I'm afraid I am none the clearer about what this means for the future of WhatsApp, iMessage and Skype. So if anybody has a clue about how we can keep encryption without retaining a "safe space" for bad people, please do let me - and No 10 - know.