Games and animation: Tackling the UK's creative skills shortage

- Published

Visual effects for the new James Bond film, Spectre, are being produced by UK-based Double Negative

A new qualification in video game design, animation and visual effects has been created to try and tackle what the industry says is an acute skills shortage. How effective can it be?

In a dark screening room on the fourth floor of visual effects firm Double Negative's plush London office, double Oscar-winner Paul Franklin talks up his industry's role in today's biggest blockbusters.

"Visual effects are at the heart of storytelling," he tells the Victoria Derbyshire programme.

"If we're talking about Paris folding up in Inception or Matthew McConaughey falling into a supermassive black hole in Interstellar, you need visual effects to go to those places."

British companies have won three of the last five Academy Awards for best visual effects. Mr Franklin and his team collected two personally for Inception in 2011 and Interstellar in 2015.

Yet, despite saying it wants to hire in Britain, Double Negative - with a 50-strong HR department always on the lookout for potential employees - says it still struggles to find candidates up to the job.

Oscar winner Paul Franklin: 'We can't find staff'

"We are looking for a new type of artist, who understands science and physics - or at the very least has an understanding of what can be done with hardware and software. It's very difficult to find staff with the right skills," Mr Franklin says.

His own background is in fine arts and video game design, but he works alongside colleagues with degrees in astrophysics and engineering.

In total, the company employs around 900 people in the UK. It is currently putting the finishing touches to the new James Bond film, Spectre.

"Creativity isn't necessarily confined to being able to draw a picture," he explains.

For Interstellar, special software was written to simulate the way gravity shapes time in space, with graphics driven entirely by Albert Einstein's equations for general relativity. The results it generated for black holes were accurate enough to be published in a scientific journal.

Producing graphics of a black hole for Interstellar led to new scientific insight being uncovered

But recruiting at this level is tricky.

Research from the government-funded NextGen Skills Academy in April 2015 indicated that 47% of companies in the visual effects, animation and video games industry were experiencing a skills shortage - compared with 5% of employers across other areas of the UK economy.

The answer, it believes, is to change the way keen, young British animators and programmers are taken on.

It has been given £6.5m of funding and resources - from employers and the government - to train the next generation. Industry backers including Pinewood Studios, Sony Computer Entertainment Europe and Double Negative.

Its first qualification - a level three NVQ in game design, animation and VFX [visual effects] - will launch at five colleges in England from September.

The two-year course, aimed at 16-year-olds straight out of GCSEs, is pitched as the first vocational alternative to the standard academic route and is equivalent to three A-levels.

Grand Theft Auto - produced by Edinburgh-based Rockstar Games - is the world's largest selling gaming franchise

"We are a growth sector, and we simply can't have a lack of skills holding back these three parts of the economy," says NextGen's managing director Gina Jackson about an industry worth £6bn to the UK.

"We are not able to get the right people, we are not getting women in to tell their stories. We can do a lot more to make the UK a better place to make games, films and animations."

The idea behind the new course is to give students a broad grounding in technical and vocational skills. From 3D-modelling to setting up their own freelance business.

At 18 years old, they are expected to go straight into a small number of new technical apprenticeships with British companies, or into a related university course in game design or animation.

Courses will take place in five colleges across England

But as with all new qualifications there are risks.

Visual effects houses and video game makers are notoriously secretive about the technology they are using.

Big budget titles now in the very early stages of development may not reach the shops or the cinemas for another three or four years.

There is a danger that students on a two-year vocational course will be taught technical skills that will already feel out of date by the time they qualify.

While industry figures - in public at least - are supportive of the new initiative, in private some have reservations.

One manager in the VFX industry said these types of vocational courses often launch with a bang only to be neglected by colleges as applications dry up after a few years.

A senior source in the video game industry said - if pressed - he would always recommend students to take a straight academic course like mathematics A-level if possible.

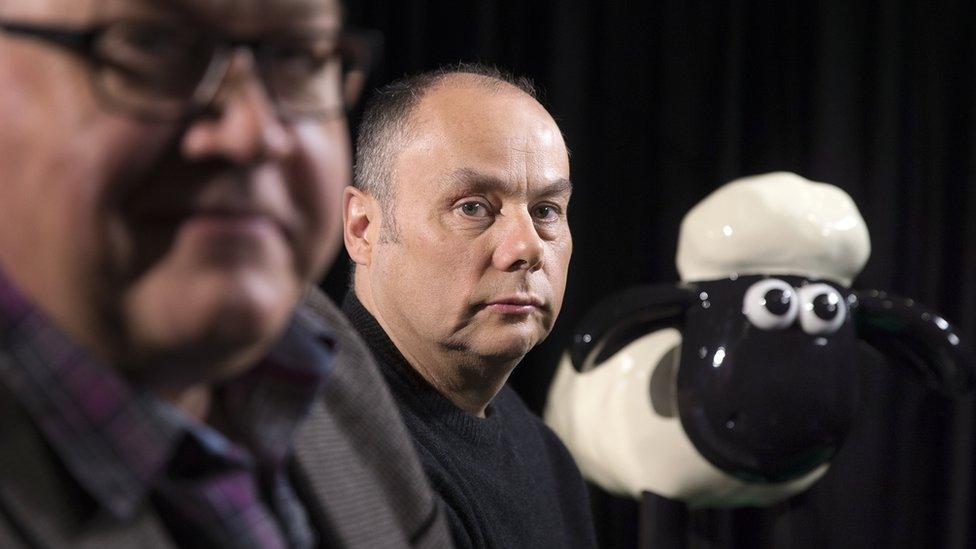

Almost 5,000 people are employed by the UK animation industry, including Shaun The Sheep creator Aardman Animations

The people behind the new qualification accept it might not be for everyone, but say it offers a different way into a well-paid, competitive industry for a certain type of student who might be currently overlooked.

"You are taking a gamble when you take A-levels, you are making decisions and closing off options," says Ms Jackson.

"With this course you are not. You can go on to university or a high level apprenticeship. And you can find out what you are good at when you are 16 years old, without having to wait until you are 21 or 22."

Watch the full film on the Victoria Derbyshire website.

- Published23 June 2015

- Published21 February 2015

- Published17 July 2013

- Published14 May 2011