Ada Lovelace: Opium, maths and the Victorian programmer

- Published

Where's the reboot button? Charles Babbage's Analytical Engine - the Victorian computer that never was

An exhibition showcasing the work and life of Victorian mathematician Ada Lovelace opens at the Science Museum in London this week.

Ms Lovelace is widely described as the world's first computer programmer because of her work with inventor Charles Babbage on his idea for an "analytical engine" in the 1800s.

The small exhibition includes a working model of the machine, which was never built because of funding issues.

Also on display is a lock of her hair.

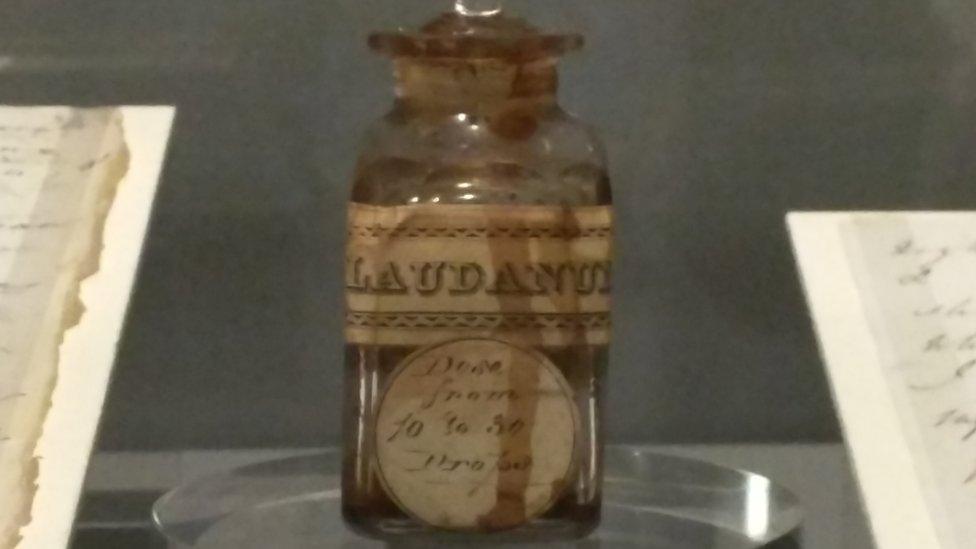

Ada Lovelace was often unwell and was prescribed the opiate laudanum, to be taken with wine, by her doctor.

She was concerned that "too much mathematics" was making her ill and her tutor, Augustus De Morgan, appeared to agree with her, saying that the work was "beyond the strength of a woman's physical power of application", according to the display.

Nowadays she would probably have been signed off with work-related stress.

"I think she was working quite hard - she was definitely really trying to study as hard as she could," said the assistant curator Katherine Platt from the Science Museum.

Doctor's orders: laudanum and wine

"Potentially she thought she was doing a little bit too much."

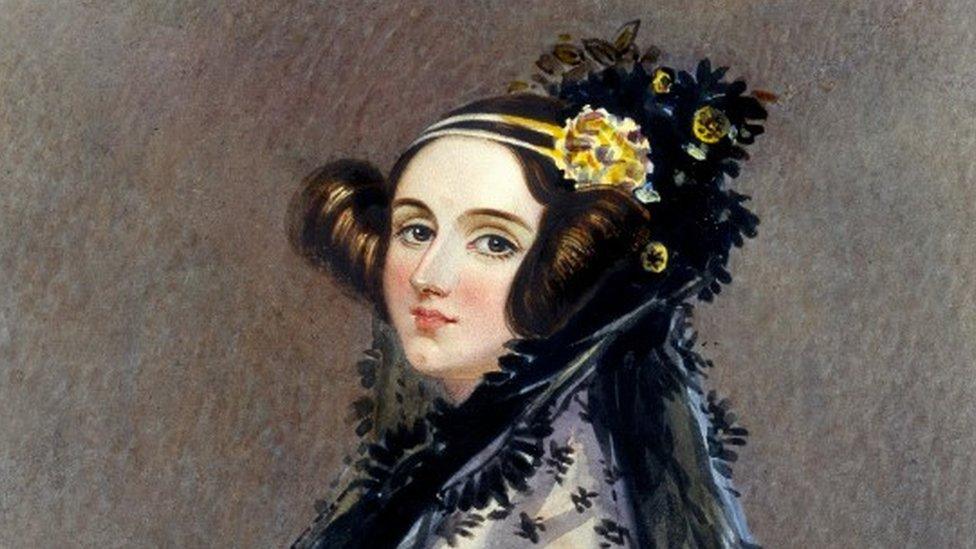

Personal items on display include a lock of Ada's hair and an enormous portrait of her, painted when she was married, wearing a lavish white dress.

Accounts suggest however that she was not very pleased with the result, describing her jaw in the picture as "big enough to write the word mathematics upon".

Ada Lovelace was the daughter of the poet Lord Byron and mathematician Annabella Milbanke.

"Intelligent she might have been, but she was also manipulative and aggressive, a drug addict, a gambler and an adulteress," said mathematician Hannah Fry, who made a BBC documentary about her.

"It's a beautiful demonstration that whoever you are, whatever your character, there is a place for you in science."

The portrait of Ada Lovelace in the white dress is not the only one on display in the Science Museum

Ada Lovelace was introduced to Charles Babbage by her mother at the age of 17 and was entranced by his Difference Engine which she described as a "thinking machine".

She worked on some notes about its successor, the Analytical Engine, translating an article by an Italian scientist and adding her own calculations.

"She was hoping that would be a starting point for greater things for herself," said Ms Platt.

"She really wanted the Analytical Engine to be completed - but there were lots of funding difficulties unfortunately. Babbage struggled to get government funding."

Had he been successful, the computer revolution may have begun a lot sooner.

"Steam-powered computing would have been a wonderful thing to see," said Ms Platt.

- Published14 September 2015

- Published18 October 2013