Could hackers break my heart via my pacemaker?

- Published

Marie Moe wants to be able to examine the code in her pacemaker

"I just found myself lying on the floor. I didn't know what happened," Marie Moe said.

The Norwegian security researcher had been drinking orange juice; now she found herself surrounded by broken glass.

"The juice was in my hair - I thought I must have hit my head and maybe I'm bleeding. It was a frightening moment."

After passing out, Marie was diagnosed with a heart problem, and had a pacemaker implanted. It sits just beneath the skin, marked by a thin white scar, a small computer that keeps her alive.

Previously Marie worked for the Norwegian Computer Emergency Response Team; now she's employed by Sintef, an independent research organisation.

While nations spend hundreds of millions defending critical infrastructure from cyber-attacks, Marie wonders if the computer inside her is secure and bug-free - she still hasn't been able to find the answer.

It's a frustration the expert audience in the lecture theatre at the William Gates Computer building in Cambridge greeted with sympathy.

She had been invited to speak by Cambridge University's Computer Security Group and the Centre for Risk Studies. The theme of her presentation was what it feels like to live with a "vulnerable implanted device".

When Marie first had her pacemaker fitted she downloaded the manuals. She discovered it had not one, but two wireless interfaces.

One enables doctors to adjust the pacemaker's settings via a near-field link. Another, slightly longer-range, connection lets the device share data logs via the internet.

Hearts are now part of the Internet of Things, she realised.

The first peer-reviewed paper describing an attack on a heart device that exploited these interfaces was produced by a team led by Prof Kevin Fu of the University of Michigan in 2008.

The late security researcher Barnaby Jack claimed to have been able to attack a heart device from up to 50ft away.

They made a combination pacemaker and defibrillator deliver electric shocks, a potentially fatal hack had the device been in a patient rather than a computing lab.

In 2012, security researcher Barnaby Jack demonstrated an attack using the radio-frequency interface on a heart device. Unlike Kevin Fu's work, Barnaby Jack said he was able to launch his attack from a laptop up to 50ft (15m) away.

Mr Jack, who has since died, was reportedly inspired by an episode of the TV show Homeland where an attack is carried out via pacemaker.

Fears of assassination by pacemaker have certainly entered the public consciousness.

Former US Vice-President Dick Cheney told CBS News that in 2007 he'd had the wireless functions in an implanted heart device disabled out of concerns about security.

Under the watchful eye of Simon Hansom, a cardiologist at Papworth Hospital in Cambridge, a patient is being fitted with the two wires that will connect the pacemaker to their heart.

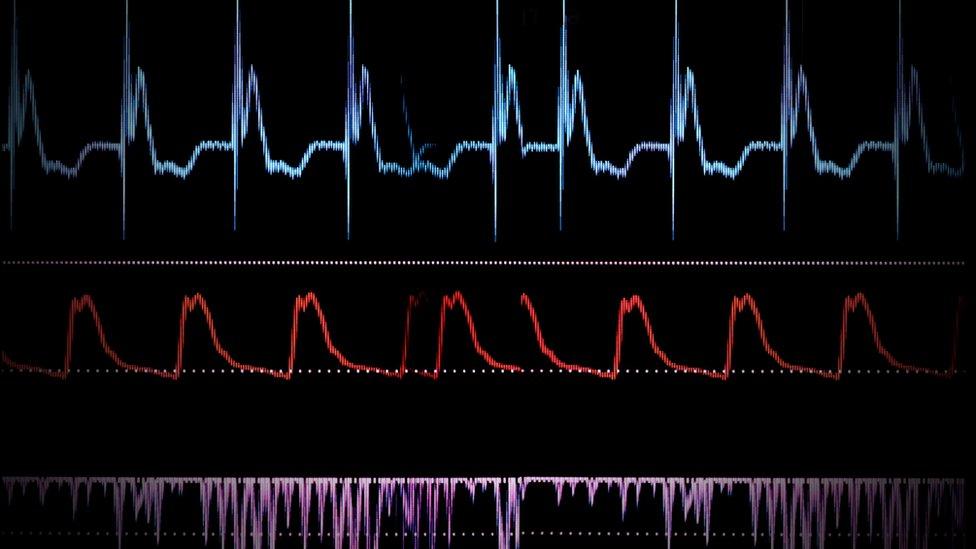

There's only a little blood visible, and from behind a sterile screen a monitor shows a live X-ray of the cables moving into the body.

"To the lay person, they probably think the pacemaker has the same wireless you have at home," he said. "It's not the same - it's very different," he said.

He believes hacking is a purely theoretical risk: "The only significant effort I've seen took a team of people two days, being within 20cm of the device, and cost around $30,000."

Prof Fu, who led that research, is less concerned than he was,

"The good news is that this model is no longer sold and the risks have been addressed," he told the BBC's PM programme.

In general security is better. It's not a completely solved problem but businesses have "learned quite a bit over the last seven or eight years in improving security engineering", he said.

Marie Moe is careful not to overstate the risk of hacking - she fears programming mistakes more.

Not long after having her pacemaker fitted, she was climbing the stairs of a London Underground station when she started to feel extremely tired. After lengthy investigations, Marie says, a problem was found with the machine used to alter the settings of her device.

Marie Moe wants to be able to examine the code in her pacemaker

To check that code is secure and bug-free, Marie would like to be able to examine the programmes that control her pacemaker. But although the pacemaker is inside her body, the vendors have not shared the code inside her pacemaker.

"It's a computer running my heart so I really have to trust this computer and it's a little bit hard for me because I don't have any way of looking into the software of this device."

Marie would like to see more third-party testing. She's a member of I Am the Cavalry, external, a grassroots organisation that works on cybersecurity issues affecting public safety.

The challenge, according to Kevin Fu, is to find a compromise between the commercial interests of manufacturers anxious to protect their intellectual property and the needs of researchers.

After her talk, Marie joins a BBC interview with cardiologist Andrew Grace at his office at Cambridge University.

He retrieves an implantable defibrillator in a small plastic bag; it's about the size and shape of a jam-jar lid.

'Transformative'

Marie has been able to run a half marathon thanks to her pacemaker.

Andrew Grace says the devices are "transformative"; if you need one, he and Marie agree, you shouldn't be put off by colourful cyber-assassination tales in TV dramas. But that doesn't mean security isn't important.

In the summer, American regulators told hospitals to discontinue using one make of drug infusion pump because of cybersecurity concerns.

Had it been an implanted device, like a pacemaker, that might have meant removing it surgically from patients.

Andrew's colleague, cardiologist Simon Hansom believes security has to be a priority.

The wireless aspect - "being able to monitor people in their own homes, get up-to-the-minute checks on the devices" - is very useful, Mr Hansom says, but the security needs to be right first time.

"It's better to know about this now and be planning the security rather than make a retrospective change."

- Published9 June 2015

- Published26 July 2013