Keeping football tough but safe by spotting concussion

- Published

- comments

WATCH: Could tech make American football safer?

Many sports are dangerous, but few are dangerous by design.

For years the powers-that-be behind American Football tried to hide it, but it became too serious. The more it was studied, the taller the pile of evidence became.

To succeed in a game where brute force is part of the DNA, you must throw in all your body can manage. And for decades of American Football, that meant your head too.

Now researchers have discovered that long-term head injuries among professional American Footballers are not just possible, they are probable.

A 2015 study looked at brains belonging to deceased ex-NFL players who had agreed to be part of the study before they died. They found a pattern: of the 91 brains examined, 87 of them showed the players suffered from the same condition.

It is Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy, CTE, and it is a condition brought on by regular trauma to the head, a regular occurrence for players at every level of American Football, not just the big leagues. It can lead to dementia and Alzheimer's disease.

The study was the latest piece of unpleasant reading for the NFL who, fearing what it could mean for the future of the sport, initially did what it could to avoid the subject.

Seven-year secrecy

It was Dr Bennett Omalu - a Nigerian forensic pathologist - who pioneered research, putting two and two together to work out what was going on.

He was examining former Pittsburgh Steelers player Mike Webster, who had died suddenly, in 2002.

It took the NFL seven years to publicly acknowledge what Dr Omalu had found that day.

Will Smith has been promoting Concussion this week in Spain

The battle to have the findings acknowledged by the NFL - and indeed, the American people - has been immortalised in Concussion, a new film starring Will Smith.

Dr Omalu's research meant families now had evidence to back up what they had long feared - that the sport had prematurely taken their loved ones.

The lawsuits began. How much did the teams know? Why did they not act? Who should be held responsible?

Millions of dollars, per affected player, were won. Thanks to the court rulings, concussion in football had rapidly became more than an ethical issue - it was a financial one too.

Finally, the NFL began to listen. Sweeping rule changes were put in place. The most controversial, and theatrical, was the new power given to extra officials who watched closely from the stands.

Aided by binoculars, and replay technology used by broadcasters, they are able to pull a player off the field immediately if they think they have had a bad knock to the head.

Like telling a pummelled boxer he has been beaten, the concussion decisions rarely go down well. It leads to temper tantrums from players and management, boos from the crowd, and onlookers such as Donald Trump crowing that the sport has gone "soft".

Stanford tests

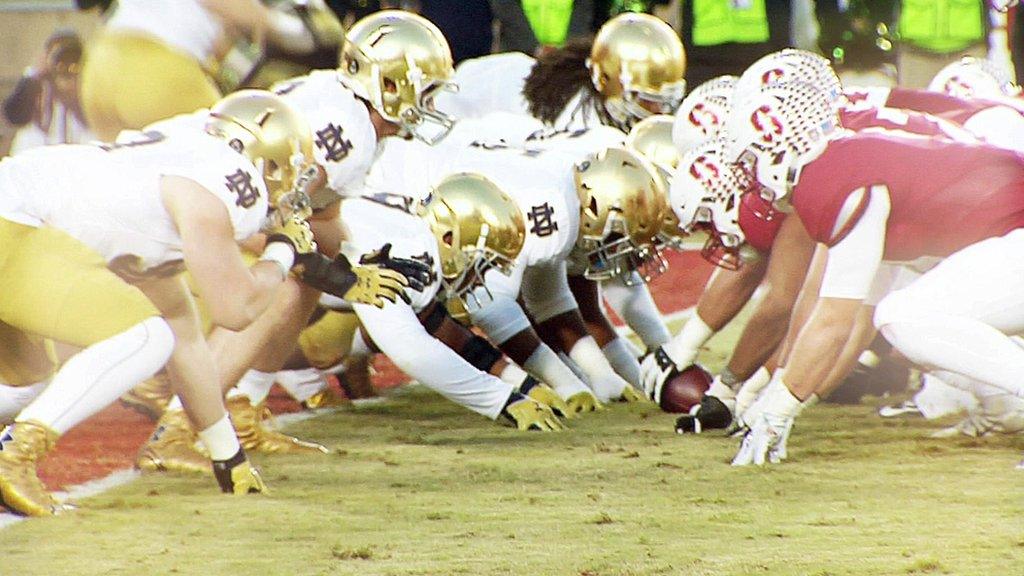

College football in the US is just as affected. While university sports in the UK are witnessed by a handful of friends and family - with the Boat Race the exception - the college game here is massive.

Stanford Stadium holds 50,000, and is home to the beloved Cardinal. Here the binocular-holding experts are so isolated and free from pressure the match organisers refused tell us exactly where they were.

Stanford Cardinal wide receiver Michael Rector drops a pass while being covered by Southern California Trojans cornerback Adoree Jackson, December 2015

No bother - because we were actually there to meet a team working on some ground-breaking technology being implemented right across the college football scene. It has the potential to not only make the sport safer, but to stop pulling players off the field unnecessarily.

If a Cardinals player has a hit to the head, they are immediately handed over to neurosurgeon Dr Jam Ghajar and Stanford Athletics head Scott Anderson, who are waiting at pitchside.

The player puts on an Oculus Rift, the virtual reality designed, originally, for video gaming.

Special software - loaded on to a Microsoft Surface tablet - uses the Rift to detect a player's eye movements with great accuracy. After a series of exercises, in which the footballer must follow a dot around the screen with his eyes, an assessment is made.

Erratic eye movements, or a failure to keep up, are a good hint that the brain has taken a knock that may be more serious than mere dizziness. (The same method can also be used, as this reporter found out, to detect sleep deprivation.)

It means the player can see for themselves that they are hurt - a pictorial representation about why it is unsafe to continue.

And on the flip side, and at a time when officials are being told to err on the side of caution, it makes it safer to send players back on with certainty that they are fit and able.

The software is being trialled at several college teams across the US. It is not approved by the Food and Drug Administration - a respected but lengthy process - but the hope among Dr Ghajar and his team is that it one day will be.

Their efforts, and several like it across the sport, are striving to keep America's most bombastic sport entertaining but, above all else, safe.

Follow Dave Lee on Twitter @DaveLeeBBC, external and on Facebook, external.

- Published28 January 2016