Is your smartphone listening to you?

- Published

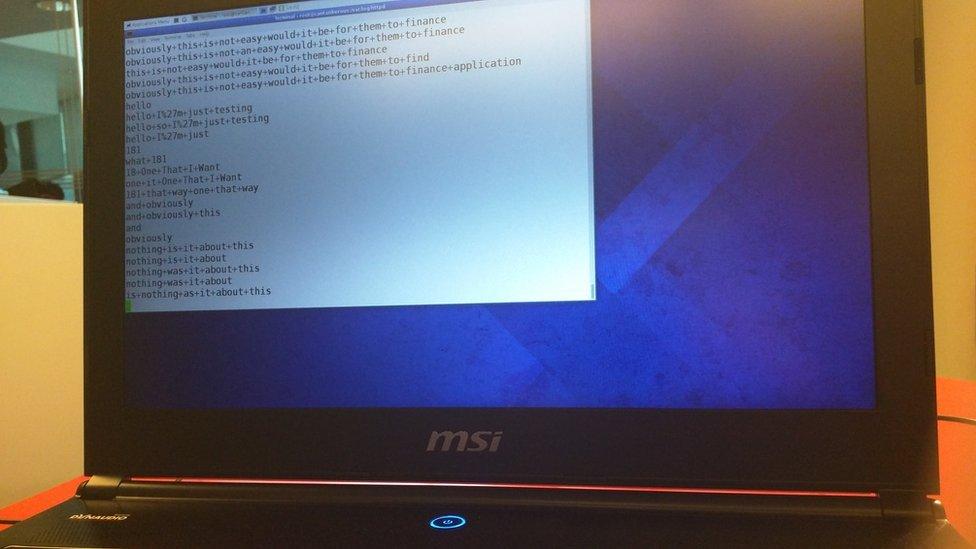

Watch: Expert creates app that spies on its mobile owners' conversations

It all began with a car crash.

I was doing some ironing when my mum came in to tell me that a family friend had been killed in a road accident in Thailand.

My phone was on the worktop behind me.

But the next time I used the search engine on it, up popped the name of our friend, and the words, "Motorbike accident, Thailand" and the year in the suggested text below the search box.

I was startled, certain that I had not used my phone at the time I had had the conversation - my hands had been full.

Had I started to look the details up later on and forgotten? Or was my phone listening in?

Almost every time I mentioned it to people they had a similar story, mainly based around advertising.

One friend complained to her boyfriend about a migraine, her first ever, only to find the next day she was being followed on Twitter by a migraine support group.

Another had an in-depth chat with her sister about a tax issue, and the next day was served up a Facebook advert from tax experts offering advice on that exact issue.

But how did you know I was just listening to the Rolling Stones?

Many said they were discussing particular products or holiday destinations and shortly afterwards noticed advertising on the same theme.

Community website Reddit is full of similar stories.

One reporter mentioned his male colleague seeing online adverts for sanitary pads after discussing periods with his wife in the car.

But surely if the microphone was activated and the handset was sending data, battery life would be even worse than it is now and individual data usage would be through the roof?

Tech challenge

I challenged cybersecurity expert Ken Munro and his colleague David Lodge from Pen Test Partners to see whether it was physically possible for an app to snoop in this way.

Could something "listen in" at will without it being obvious?

"I wasn't convinced at first, it all seemed a bit anecdotal," admitted Mr Munro.

However, to our collective surprise, the answer was a resounding yes.

They created a prototype app, we started chatting in the vicinity of the phone it was on and watched our words appear on a laptop screen nearby.

"All we did was use the existing functionality of Google Android - we chose it because it was a little easier for us to develop in," said Mr Munro.

"We gave ourselves permission to use the microphone on the phone, set up a listening server on the internet, and everything that microphone heard on that phone, wherever it was in the world, came to us and we could then have sent back customised ads."

The whole thing took a couple of days to build.

It wasn't perfect but it was practically in real time and certainly able to identify most keywords.

The battery drain during our experiments was minimal and, using wi-fi, there was no data plan spike.

"We re-used a lot of code that's already out there," said David Lodge.

"Certainly the user wouldn't realise what was happening. As for Apple and Google - they could see it, they could find it and they could stop it. But it is pretty easy to create."

"I'm not so cynical now," said Ken Munro.

"We have proved it can be done, it works, we've done it. Does it happen? Probably."

Google responds

The major tech firms absolutely reject such an idea.

Google said it "categorically" does not use what it calls "utterances" - the background sounds before a person says, "OK Google" to activate the voice recognition - for advertising or any other purpose. It also said it does not share audio acquired in that way with third parties.

Its listening abilities only extend to activating its voice services, a spokesperson said.

It also states in its content policy for app developers, external that apps must not collect information without the user's knowledge. Apps found to be breaking this are removed from the Google Play store.

Facebook also told the BBC it does not allow brands to target advertising based around microphone data and it never shares data with third parties without consent.

It said Facebook ads are based only around information shared by members on the social network and their net surfing habits elsewhere.

Other big tech companies have also denied using the technique.

Coincidence

There is of course also a more mathematical explanation - the possibility that there is really no connection at all between what we say and what we see.

Prof David Hand argues that anything can happen, given enough opportunities.

Mathematics professor David Hand from Imperial College London wrote a book called The Improbability Principle, in which he argued that apparently extraordinary events happen all the time.

"We are evolutionarily trained to seek explanations," he told the BBC.

"If you see a sign you know is associated with a predator you run away and you survive.

"It's the same sort of thing here. This apparent coincidence occurs and we think there must be explanation, it can't be chance. But there are so many opportunities for that coincidence to occur.

"If you take something that has a tiny chance of occurring and give it enough opportunities to occur, it inevitably will happen."

People are generally more alert to things that are currently occupying them, such as recent conversations or big decisions like buying a car or choosing a holiday, he added.

So suddenly those sorts of messages stand out more when they may have been in the background all the time.

Beautiful

Prof Hand is not immune to the lure of coincidence himself.

When his book was published another author published a very similar title at the same time. The author of The Coincidence Authority, John Ironmonger, shared the same birthday as Prof Hand and was based at the same university as his wife.

"These sorts of things happen," he said.

"Just because I understand why it happened doesn't make it any less beautiful."

- Published2 March 2016

- Published5 August 2015

- Published29 January 2015