Google AI takes on the 'world's Go champion'

- Published

Go champion Lee Se-dol says he is not sure he will be the "clear winner"

You have to feel for Lee Se-dol. He speaks quietly. His fingers shake as he talks to the BBC. He is nervous.

But you would be if you were representing the human race against a very clever machine. Mr Lee is considered the world champion at baduk (or Go as the board-game is known through much of the world) thanks to his number of wins over the past decade.

He's due to play a computer with a programme devised by Google. The winner will take away about a million dollars - not that AlphaGo, as the programme is called, will be able to spend it.

AlphaGo has already beaten the European champion but, experts say, this is easy-peasy compared to taking on the masters in Asia - it would be like beating some non-league football side compared to playing Barcelona.

Lee Se-Dol - seen on the right - will play Go against Google's DeepMind computer-powered AI in five matches played between 8 March and 15 March

Mr Lee is the reigning human champion of the planet (though a Chinese contender is running close).

"Playing against a machine is very different from an actual human opponent," the world's Number 1 told the BBC.

"Normally, you can sense your opponent's breathing, their energy. And lots of times you make decisions which are dependent on the physical reactions of the person you're playing against.

"With a machine, you can't do that."

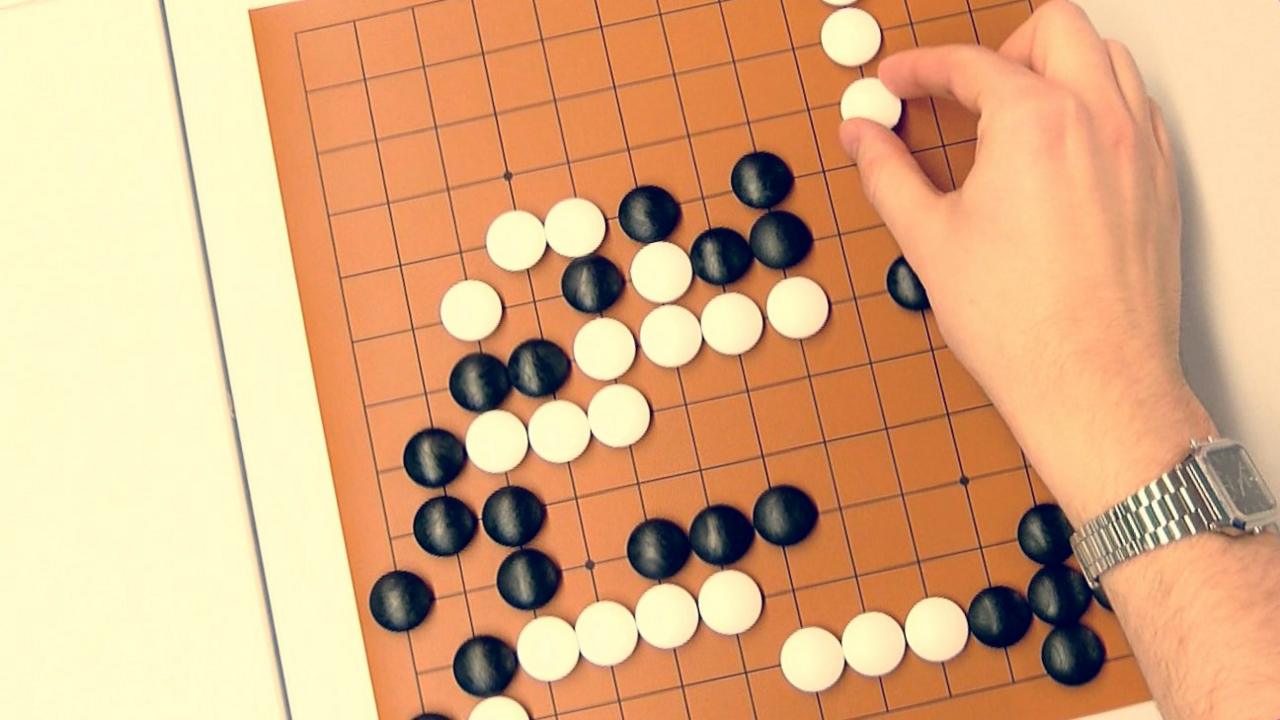

That's because emotion and character play a large part of the game. In chess, there are fewer possible permutations because it's played on a board of eight squares by eight (compared with 19 by 19 on a Go board).

A brief guide to Go

Self-discipline

As the British Go Association explains: "At the opening move in chess there are 20 possible moves. In Go, the first player has 361 possible moves.

"This wide latitude of choice continues throughout the game," it adds.

"At each move the opposing player is more likely than not to be surprised at his opponent's move, and hence he must rethink his own plan of attack. Self-discipline is a major factor in success at this game".

The number of permutations in a game of Go is greater than the number of atoms in the universe, according to the Nature science journal, "so it can't be solved by algorithms that search exhaustively for the best move".

Google's DeepMind division beat the European Go champion in October

For this reason, it's not just a matter of the cold calculus of a computer working out permutations - or so Lee Se-dol hopes.

But he doesn't seem sure: "I've been telling people that I was certain that I would be the winner of all five matches. But Google - which developed the programme - seems to be quite confident, too".

Value judgements

He is spooked by the idea that the computer can adapt its game as it learns its opponent's style - his mechanical opponent will adapt its style as it studies his.

This idea that a computer can learn how to ultimately beat a human has frightening possibilities if it were ever eventually translated into weapons, for example.

The best Go players typically rely on a mix of skill and instinct

"I hope this advanced technology will be used for useful things but I do fear that perhaps things may happen and turn out like a scene from a science fiction film," Mr Lee says.

"I think things like intuition, being able to make individual value judgments are all part of human character.

"If I do get a sense that a machine is starting to act or think like me, it will be frightening. But also we'll know for sure that this kind of technology now possesses the true potential for beneficial solutions and help the way we live".

Brute-free attack

Go was invented by the Chinese 2,500 years ago or thereabouts. It's sometimes called an "imperial game" because it's about controlling territory (on the board) as opposed to chess which is about capturing the king.

Both are too complex for a computer to predict every move with utter certainty, through the brute force of computing power. Computers - like humans - have to assess.

As the Nature journal explained: "Chess is less complex than Go, but it still has too many possible configurations to solve by brute force alone. Instead, programs cut down their searches by looking a few turns ahead and judging which player would have the upper hand."

It added that recognising winning positions was also hard to do since Go's stones have equal values and can have "subtle impacts far across the board".

Lee Se-Dol comes from South Korea and will face off against Google in Seoul

AlphaGo learned the pattern of stones by ingesting 30 million positions from expert games..

It worked out which positions were likely to be winning ones, and then - and this is the master-stroke - it played itself repeatedly to improve its own play. In other words, it learned.

So, this five-match tournament between man and machine feels like a contest for the supremacy of the future.

It's also David versus Goliath.

In the Four Seasons Hotel in Seoul, Google has a big public relations operation. Amidst all the glitz and smooth operatives of the corporate behemoth, Lee Se-dol seems like a small, shy figure, with a quiet voice and nervous hands.

Shy man versus big machine: who do you want to win?

- Published5 February 2016

- Published28 January 2016

- Published27 January 2016