The rules for flying domestic drones

- Published

The risks of collision multiply when drones are flown near airports, warned the CAA

Police are investigating a reported mid-air collision between a drone and a British Airways jet from Geneva that was approaching London's Heathrow Airport.

BA said the Airbus A320 was not damaged when the object hit the nose of the plane, which landed safely with no injuries reported to anyone on board.

Since April last year there have been 25 near misses between aircraft and drones, figures from the UK Airprox Board, external suggest. A dozen of these were denoted "Class A" which indicates there was a serious risk of collision.

The Heathrow incident comes only weeks after the British Airline Pilots Association called for rules governing the use of drones to be enforced more strictly.

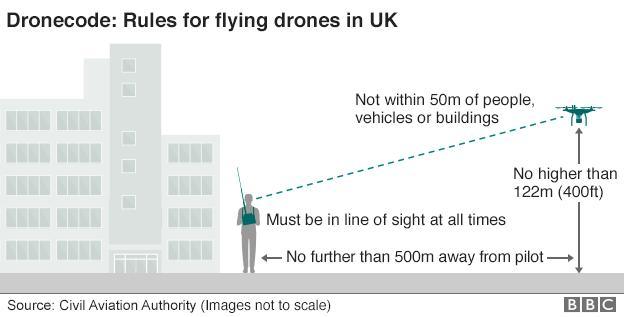

UK rules on flying drones, called the dronecode, have been drawn up by the Civil Aviation Authority (CAA). The CAA code says that drones should:

be visible at all times

be flown below 400ft (122m)

not be flown over congested areas

In addition, it says, unmanned aircraft fitted with a camera should not be flown within 50m of people, vehicles or buildings.

They should also not be flown over crowds or congested areas.

Pilots of drones with cameras must also be mindful of privacy when taking pictures.

Those using a drone to make money, eg for aerial photography, must get permission from the CAA and complete a training programme to demonstrate their competence with the craft.

Illegal flight

Drone operators should avoid crowds and other congested areas

However, these rules do not explicitly bar a smaller drone being flown near an airport even though the skies around such locations are designated as "controlled airspace".

"Anything under 7kg could, in theory, fly in controlled airspace," said a CAA spokesman.

"But by doing so it will almost certainly breach the other regulations such as endangering an aircraft or flying in a congested area."

UK laws say that anyone found guilty of endangering an aircraft by any means, not just with a drone, could face up to five years in jail.

"Do not fly anywhere near an airport," said the CAA spokesman.

"Even though you may be flying no higher than 400ft, the chances of getting too close to an aircraft get higher the closer you get to an airport."

He urged people to exercise "common sense" when flying their drones recreationally.

In the UK, two people have been prosecuted for the "dangerous and illegal" flying of a drone. Fines were imposed in both cases.

"It would be easy to do something daft," said Martin Maynard, a commercial drone pilot who uses his craft for environmental monitoring.

Mr Maynard said he had seen many posts on social media sites showing recreational drone pilots being reckless.

"One of the big trends is people seeing how far away can they fly their drone," he said. "With big antennas some can reach three or four miles."

The CAA rules state that a drone should be kept in visual line of sight at all times and no more than 500m (0.3miles) from its pilot as a maximum.

However, said Mr Maynard, even at relatively close distances of 200m or so, drones could be hard to pick out.

"If you lose sight of that little dot then you have lost it completely," he said.

Fire risk

Modern jet engines are good at handling bird strikes and internal failures

Researchers at Cranfield University are engaged in a project to find out how much damage a drone could do if it hit an aircraft or was sucked into an engine.

"With small drones, the risk is not that great," said Dr Ian Horsfall, professor of armour systems at Cranfield. "It's not that different to a bird strike."

In mid-March, scientists at George Mason University said the risk from drones was "minimal" given the small number of strikes on aircraft by birds that did damage.

Birds such as turkey vultures and geese that significantly outweigh domestic drones were the only ones that did significant damage to an aircraft, they found.

"Big drones might be more of an issue than bird strikes," said Dr Horsfall. "And they are getting bigger and heavier over time."

Modern jet engines were generally quite good at coping when damaged by bird strike or a mechanical failure, said Dr Horsfall.

Drones can be pre-loaded with co-ordinates of restricted locations such as airports, a technique known as geo-fencing. Drones should resist being flown into these areas and many manufacturers make their craft land if they approach them.

However," said Dr Horsfall, "it's by no means comprehensive. Not every airport is listed in there."

Cranfield was now looking into the risks posed by the disintegration of the lithium batteries typically used by drones to see if they might cause a fire if they are embedded in the nose of an aircraft or elsewhere on its fuselage.

"The battery is the main weight in them and that's what you need to worry about," he added.

- Published18 April 2016

- Published13 April 2016

- Published14 April 2016

- Published16 March 2016