Would you want to talk to a machine?

- Published

Many predict online virtual assistants will replace call centre workers eventually

We might regard our semi-intelligent smartphone assistants with a mixture of affection and frustration, but our attempts at getting answers from them are going to be just the start of a much bigger conversation.

Chatbots or virtual assistants are creeping into all aspects of our lives - from boxes in the home, such as Amazon's Alexa, which can tell you your bank balance, to bots that pop up on messaging services or websites to help with your mortgage or order you a pizza.

Add to that weather bots, news bots, shopping bots, personal finance bots and scheduling bots, and it becomes clear why chatbots are rapidly becoming the "poster child of AI".

That's the view of Gerard Frith, chairman of AI consultancy company Matter, who has launched a number of bots in a range of organisations.

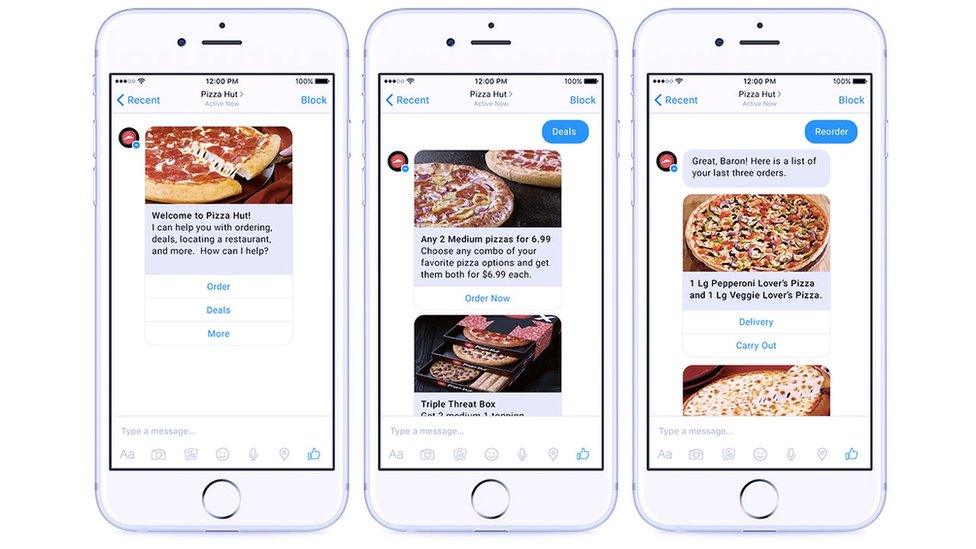

The Pizza Hut chatbot will launch on Facebook and Twitter

He has seen a marked difference in attitude between different companies.

While some are up front with customers about the fact that they are conversing with a machine, others aren't.

"When people know that they are talking to a chatbot, they are much less patient and want to escalate the call so that they can chat to a human," he told the BBC.

"Chatbots are clearly not as capable as a very good customer service person, but many people are not very good at customer service.

"So, then, chatbots do a valuable job.

"They understand when to pass a query on to a human, and they are actually often better than humans at answering complex questions."

IBM's cognitive platform Watson has always been good at interpreting natural language, so it makes sense that the technology is increasingly in-demand as a chatbot - most recently developing the Luvo platform for the Royal Bank of Scotland.

Currently being tested among bank staff who handle queries from small business customers, Luvo will eventually be let loose on all customers.

It can solve problems, without requiring human intervention, about 30% of the time.

Luvo has been designed to be "humanlike" in its interactions and is learning sentiment analysis to work out whether a customer is unhappy.

It has been trained to recognise different accents from around the UK.

Paul Chong, director of IBM Watson Europe, thinks businesses will increasingly see voice, rather than apps or web pages, as the best way to interact with customers.

Facebook now has 11,000 chatbots on its Messenger platform

"In future people won't need to go to websites, it will all be about the conversation," he said.

And chatbots were likely to change the way we converse.

"There are questions that people will ask a robot that they wouldn't ask a human," Mr Chong said.

"We are working with a couple of Australian universities, and people ask questions that they wouldn't ask a human such as, 'How do I make friends?'"

Pizza Hut is just about to launch its own chatbot, playing catch-up with rival Dominoes, which already has one.

Described as "conversational commerce", the bot will launch in Twitter and Facebook Messenger later this year.

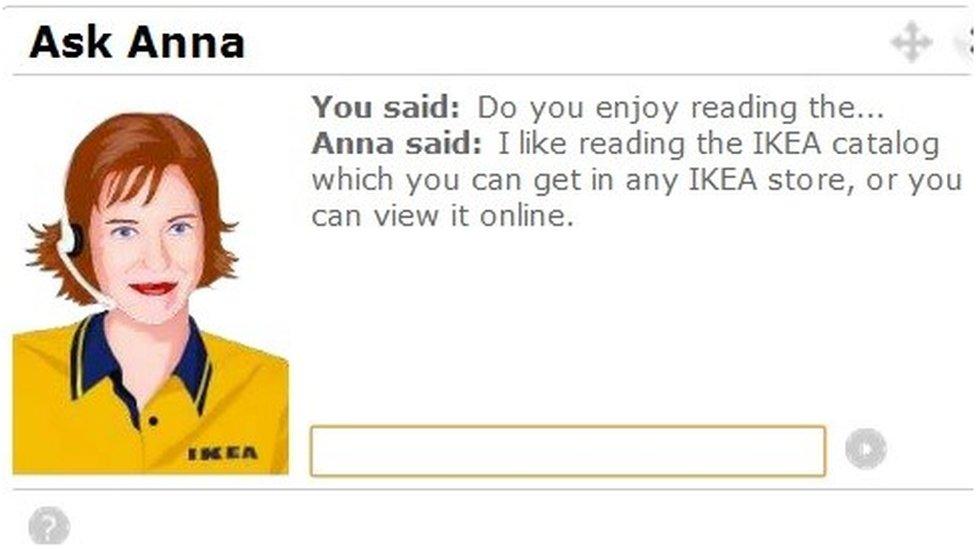

After 10 years, Ikea is retiring its chatbot, Anna

Facebook Messenger now has 11,000 chatbots, while Kik - a popular messaging platform among teenagers, unveiled 6,000 new chatbots last month alone.

Messaging apps are rapidly becoming the communication tool of choice for the young, and the top four - Facebook Messenger, WhatsApp, WeChat and Viber - now have more registered users than the top four social networks.

But not everyone is queuing up to employ a chatbot.

Ikea was one of the first companies to use the technology - launching its virtual assistant, Anna, as a way to guide people around its website.

But now it has abandoned Anna and has "no plans" to reintroduce her.

In a statement to the BBC, an Ikea representative said: "For over 10 years, our automated online assistant, Anna, has cheerfully answered people's questions on Ikea.com.

"But as times changed and technology developed, last year it was decided that it was time for Anna to move on.

"So last year "Ask Anna!" was removed from Ikea.com."

Magnus Jern, president of mobile solutions company DMI, who was involved in the launch of the mobile version of Anna, has some advice for those thinking about using a chatbot.

"In the beginning, we tried to impersonate a person, and we found that there was no reason to do that," he said.

In fact, trying to make Anna "human-like' meant that people were more likely to ask it stupid questions, Mr Jern said.

"Around 50% of questions were sex-related," he said.

"If you try too hard to be natural, it diverts from the real purpose of it, which is about giving the right answer as fast as possible."

If you are one of those people who shout down the phone at automated messages or customer support, you might not like dealing with chatbots

Customer frustration may have played a part in the demise of Anna, and it is something that others will have to be aware of.

Writing recently in Tech Crunch, external, Arun Uday, a venture capitalist and founder of mobile group chat app Tring Chat, said: "When a customer has an issue, they would most likely want to skip automated response options and speak to a real person who can fix their problem - not chat with a semi-intelligent bot dishing out some canned responses."

But Mr Jern remains more optimistic, believing not only that chatbots are here to stay but that they are likely to become far more sophisticated.

"It will get more and more difficult to distinguish between the real people and the fake ones," he said.

- Published31 May 2016

- Published12 April 2016