How will virtual reality change our lives?

- Published

Virtual Reality (VR) has been with us for many decades - at least as an idea - but the technology has now come of age.

And it's not just gamers who are benefiting from the immersive possibilities it offers.

Four experts, including Mark Bolas - former tutor of Palmer Luckey, who recently hand-delivered the first VR handset made by his company Oculus Rift - talked to the BBC World Service Inquiry programme about the future of VR.

Mark Bolas: Out of the lab

Mark Bolas is a professor at USC School of Cinematic Arts and a researcher at the Institute for Creative Technologies. He has been working in virtual reality since 1988.

VR hits on so many levels. It's a real out-of-body experience, and yet completely grounded in your body.

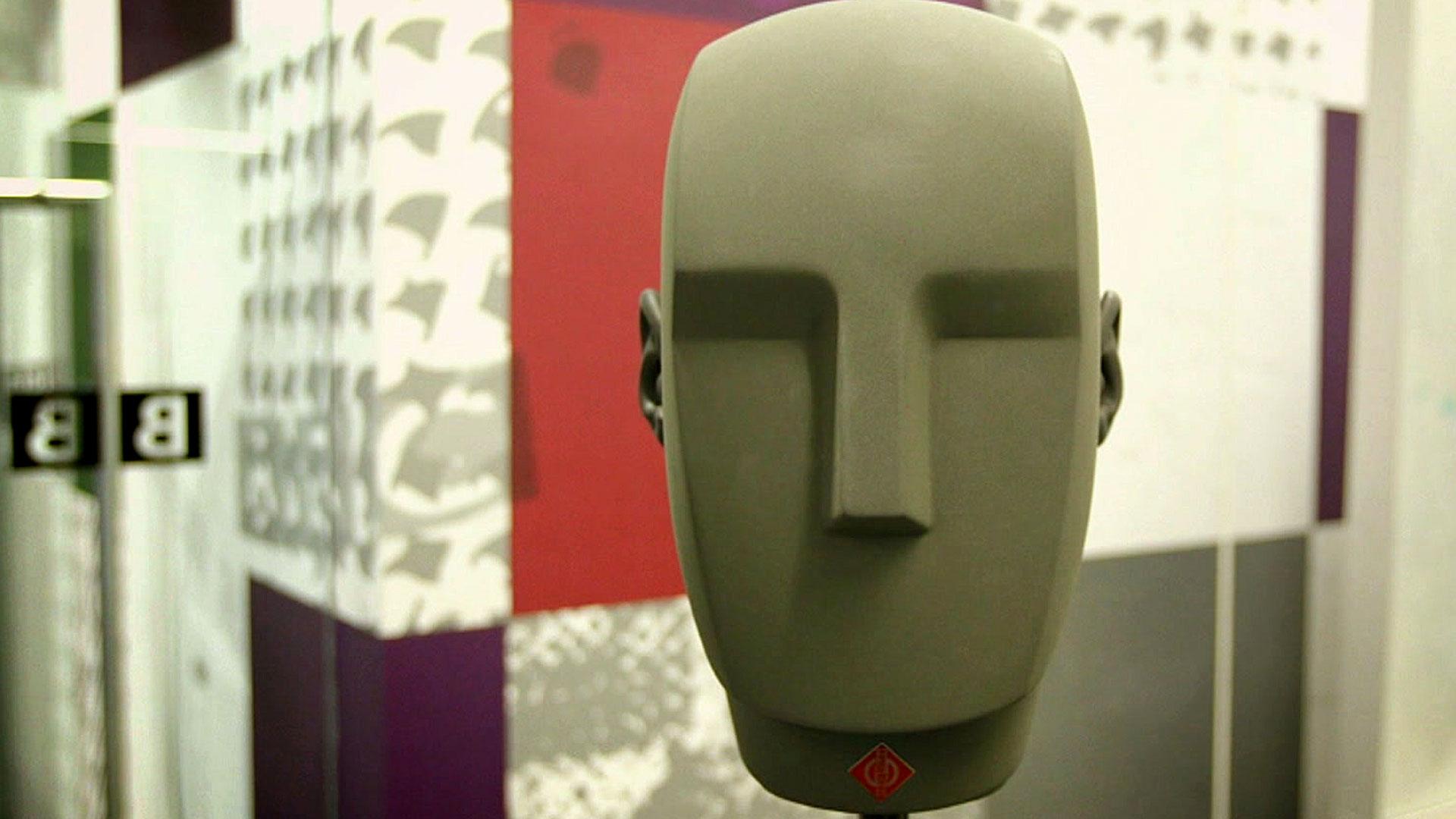

Rory Cellan-Jones virtual reality

People have always wanted to master their environment, to extend our agency. We want our hands to be able to do more; that's why we have hammers.

VR allows us to go beyond the limitations of physical tools to do anything that can be computed. If you want to create a two-mile high tower made out of toothpicks, you can do it.

I did a series of 14 different environments; one where you felt like you were very high and had to look down: that was the first time people found this sense of vertigo within a virtual environment. I did a world where you look up towards the sky and see fireworks exploding; that's just magical.

I wanted to build a tool so people could use it. The best way to do that was to stay away from the consumer market because it really wasn't ready, and to go after industrial uses.

So my company created a viewing system that actually meets the specs of modern VR.

Because it had such high resolution, commercial users could use it to solve real problems.

Automobile companies used it for car design. Oil and gas industry used it to visualise data to figure out the right place to sink a well.

The next step was to make these cheap. Consumer VR up until then had a really narrow field of view; it was like looking through a tube of paper. Peripheral vision is really important for a visceral sense, and that's what people really react to.

To find a way to make it low cost and still retain that field of view, we harnessed the power of mobile phones - the screens, tracking and processing - and we figured out a lens design that was extremely inexpensive.

It's been really fun playing all these years, but there's something more important now, which is making it a space that allows us to harness our emotions, our desire to connect with people.

I'm worried by our current computer interfaces. I watch people walking around like zombies with cell phones in their hands, and I have to manoeuvre a mouse to fill out little boxes on web forms in a horribly frustrating way. I think VR will allow us to transcend this.

I don't worry so much about where VR is going, I worry about where we currently are.

Maria Korolov: Work, rest and play

Maria Korolov is a technology journalist who has devoted her career to writing about virtual reality.

The biggest way [VR is changing the workplace] is training and simulations. If you have to train somebody on a very expensive piece of machinery, you want to do it in a simulator. The Army, for example, has been an extremely early adopter, as has the air force.

A London hospital live-streamed a patient's colon cancer surgery

One recent example was a doctor [who] practised surgery on a tiny baby's heart. He took scans of the heart, uploaded them to the computer and toured it with this little virtual reality headset, was able to plan out his surgery ahead of time, and saved the baby.

In education, the biggest change has been Google Expeditions. Google has been seeding elementary schools with over 100,000 virtual reality headsets and lesson plans. Kids are able to go on a virtual reality field trip to, say, the surface of the moon.

Gamers want something visceral. When you're riding a roller-coaster and you go down a hill, your stomach drops out: even though you know it's not real, your body reacts as if it's there. When I showed a shark simulation to people and they screamed, I laughed because, "Ha ha, they're not real." Then I put it on and the shark came at me and I screamed, because it's a physical reaction.

The adult industry is jumping into this with everything they've got because it is so compelling. I have sampled it purely from a reviewer perspective, and it felt like you were in a locker room, and you don't know where to look because everyone's naked, and the lights are too bright, and they're interacting with you. This is going to be big.

The way the internet has changed the way we communicate information, virtual reality will change the way we communicate experiences.

If I wanted to show you what it's like to cook a meal, I could invite you to my virtual apartment and take you through a virtual cooking class. If I wanted to experience a walk in the woods with you, I could take you to my favourite virtual woods.

It will make the world even smaller than it is now. It will increase the ability of people to telecommute and work together across national boundaries dramatically. It's definitely going to bring us closer together.

Skip Rizzo: On the virtual couch

Psychologist Skip Rizzo is director for medical virtual reality at the University of Southern California. He has been using VR since the 1990s when he became frustrated with the tools available to help rehabilitate people with brain injuries.

I noticed many of my clients were engaged in video games, and people that were very challenged in maintaining attention and focus in everyday activities could focus on those tasks and actually get better.

That was the first light bulb. Could we build virtual environments that represent everyday challenges that would help cognitive rehab?

We started off building virtual environments from video imagery that we had of Iraq and Afghanistan, and talked to a lot of veterans. The environments we created involved riding in a Humvee in a mountainous area, or a desert roadway.

We put somebody in a simulation that is reminiscent of what they were traumatised in, but at a very gradual level so they can handle it. The clinician can control the time of day, the lighting conditions, the ambient sounds.

The therapist tries to mimic what the patient is talking about in their trauma narrative. And eventually by confronting it with therapists, you start to see post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms start to diminish.

We've used VR to help people with high-functioning autism be more effective at job interviews. This involves having them practise their interviews with a wide range of interviewers - different age, gender, ethnic background, and different levels of provocativeness.

We know that the brain is quite good at suspending disbelief, so even though people know these aren't real people, they relate to them as if they are.

This is why VR is so compelling, because whatever is learned in those worlds hopefully will benefit how the person translates their behaviour in the real world.

Nick Yee: Vulnerable reality

Nick Yee is a social scientist who studies how people behave and interact in virtual worlds and online games.

We weren't interested in the technology for the technology's sake; the bigger question was using VR as a new platform to study human psychology.

Are we uniquely susceptible to persuasion within a virtual reality universe?

Studies show when we step into virtual bodies, we conform to the expectations of how those bodies appear.

When we're in a more attractive body, we leverage stereotypes we have about how attractive people behave.

People perceive taller individuals as being more confident, and we adopt those norms when we too are given a slightly taller body in virtual reality.

You're more likely to be persuaded by and like a person if you share similar traits, even cues as arbitrary as having the same birthday, the same first name.

Our brains are wired with all these heuristics for who we like, how easily we're persuaded.

VR is uniquely powerful in terms of its ability to manipulate bodies and faces, and hijack a lot of the soft-wiring of how our brain makes sense of the world.

We ran another study where we had a virtual presenter mimic a participant's head movements at a four second delay, while the presenter was giving a persuasive argument, and we found that people are more likely to be persuaded when they are being mimicked.

You can imagine running into a computer agent in the virtual world that sort of looks like you, and has a bit of your mannerisms, and you can imagine how much more persuasive that computer agent could be.

This ability in VR to use algorithms to make [computer agents] more likeable, or their message more persuasive, that's definitely an interesting potential use of virtual worlds.

It absolutely does worry me. We thought about this a lot at the lab. Can people inoculate themselves against these strategies? We were pessimistic. We knew from our own studies that a lot of these manipulations can be subtle to the point of being undetectable, yet still have a measurable impact. It's hard to guard against them.

The Inquiry is broadcast on the BBC World Service on Tuesdays from 12:05 GMT. Listen online or download the podcast.

- Published6 May 2016

- Published5 May 2016

- Published25 April 2016

- Published14 April 2016

- Published12 April 2016

- Published28 March 2016