'We need to defend mobility online'

- Published

Yasmin Green from Jigsaw (formerly Google Ideas) discusses its vision of a more open internet

Most people reading this article know the internet as a place with relatively few limits.

You probably have access to a mobile device. You can search for information, read the news, and communicate with people freely.

And you likely learn something new every single day as a direct result of your time online.

But for hundreds of millions of people, the internet isn't so simple.

Our lives are increasingly lived online, yet so little attention is paid to the invisible borders that prevent people and information from moving freely through the world.

Digital mobility isn't a widely examined concept, but it should be.

'Selective outrage'

In many places around the world, individuals are being targeted for their political, religious and sexual identities.

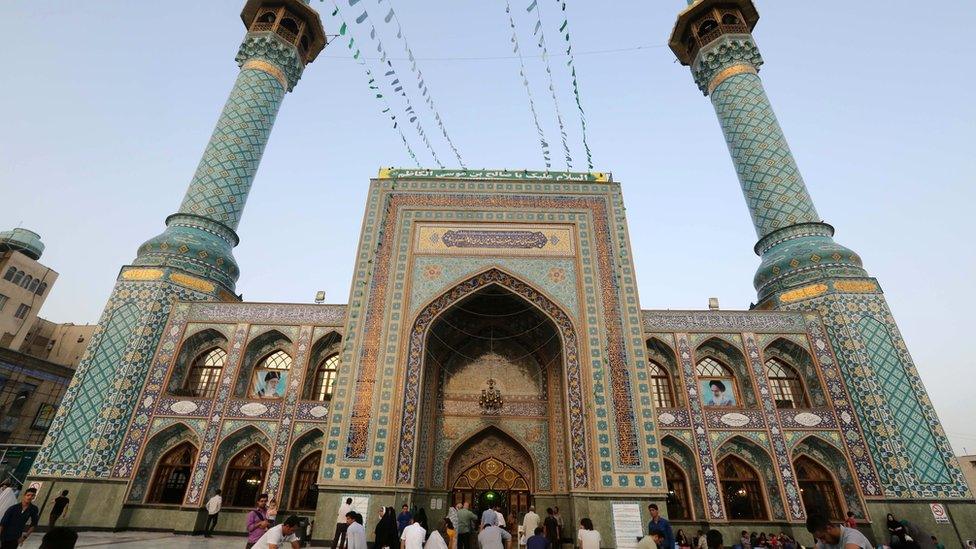

In Iran, where I was born, being gay is a sin, a crime, and the conservative clerics would have you believe it's also a myth.

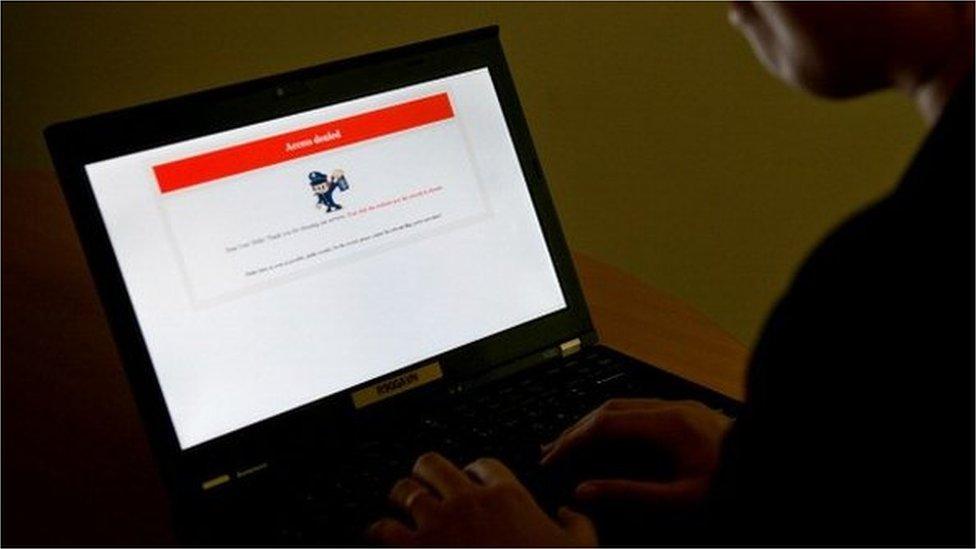

Iran is one country where there are barriers to information, says Green

The state propagates the idea that homosexuality is a manifestation of transsexuality: if you're a man who loves a man, you must be a woman trapped in a man's body. In an odd bit of selective outrage, the government even pays for gender reassignment surgery.

Every day people leave their country of birth or hometown because of homophobic harassment and persecution.

What's so harmful in the case of Iran is the barriers to accessing information — there are gay people in Iran who don't know that being gay is even a concept.

The Iranian government blocks about a quarter of all internet sites, including many that include positive messages about LGBT issues.

That sort of censorship profoundly limits Iranians' digital mobility—and leaves a vulnerable population exposed to grave danger.

So-called Islamic State fighters

Let's take another example: an ISIS fighter who wants to escape the horrors of the caliphate. I recently travelled to Iraq to interview former ISIS fighters —people who just weeks ago had volunteered to be suicide bombers.

I learned that when aspiring fighters arrive at ISIS's headquarters in Raqqa, Syria, they are forced to give up two of their most prized possessions, their passport and their mobile phone — symbols of their physical and digital mobility.

So-called Islamic State fighters have to give up their mobile phones in Raqqa

The former fighters described life in the caliphate in stark contrast to the common ISIS narrative of a group of noble warriors fighting for Muslims' rights. The recruits couldn't speak freely, move freely, or use technology.

They were prisoners in every sense. Once the new joiners completed their six weeks of obligatory religious and military training, they got their phones back.

The defectors I spoke with were the lucky ones. They had contacts in a nearby military force who coordinated their escape.

Most people aren't so lucky. If my interviews are any indication, there are many young people who know immediately upon arrival in the caliphate that they have made a huge mistake and that they want to leave, but they don't know how.

They do, however, have access to a mobile phone and wi-fi. It would be a mistake not to exploit this opportunity to reach disaffected members of ISIS.

'Fundamental right'

Although these examples illustrate seemingly isolated cases of life under severe censorship or the deprivation of information, pro-democracy think tank Freedom House reports that, two thirds of the world faces some type of repression.

Some repressive governments are using the internet as a weapon

And more governments than ever are censoring information that is in the public's interest.

It's easy to take each of the above examples as isolated cases, or to make excuses for such oppression as the result of cultural differences. But we shouldn't.

We should regard free access to information and digital mobility as a fundamental right—a right that is as crucial to human liberty as the ability to move from place to place or cross borders.

Need for constant vigilance

Fortunately, technology can play a crucial role in undermining repressive governments' attempts to censor and weaponise the internet.

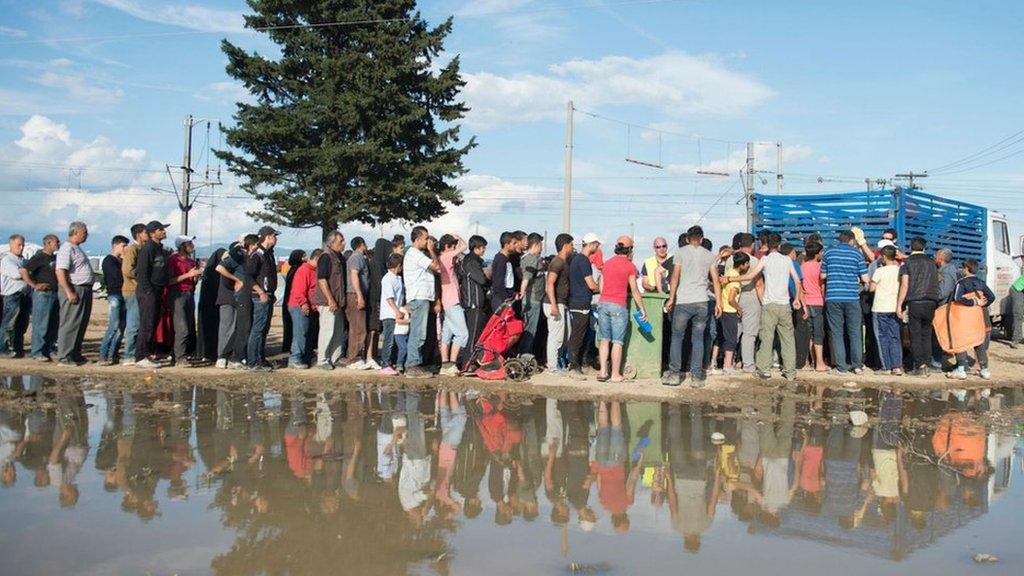

BBC News World On The Move is a day of coverage dedicated to migration, and the changing effect it is having on our world.

A range of speakers, including the UNHCR's special envoy Angelina Jolie Pitt, and former British secret intelligence chief Sir Richard Dearlove, will set out the most important new ideas shaping our thinking on economic development, security and humanitarian assistance.

You can follow the discussion and reaction to it, with live online coverage on the BBC News website, external.

A small but committed group of developers and companies are creating the next generation of proxies, circumvention tools, and cyber attack mitigation services—technological tools that allow people to access blocked content or protect websites from cyber attack—all of which make it harder for a repressive government to effectively erect borders around its internet.

Achieving digital mobility isn't inevitable, certainly not for the millions of people coming online in repressive societies.

Protecting individuals' right to access information freely requires our constant vigilance and technological ingenuity.

Such rights deserve our strongest defence.

Yasmin Green is the Head of Research & Development at Jigsaw, a technology incubator within Alphabet, Google's parent company. She is taking part in the BBC's World On the Move day.

- Published16 May 2016

- Published17 December 2015