A peek behind the curtain at GCHQ

- Published

Few get to see inside operations at GCHQ in Cheltenham

It has long been the most secretive of Britain's intelligence agencies - but, lately, GCHQ has been tiptoeing ever so carefully out of the shadows.

Last month, the signals intelligence operation opened a Twitter account - "Hello World," was its first offering - and last night its director spoke for an hour at an event where he even took questions from members of the public.

Mind you, this was friendly territory - the Cheltenham Science Festival, external in GCHQ's home town.

The session had been billed as an interview between the Times journalist Ben Macintyre and "a senior GCHQ official", but the level of security in the town's Imperial Gardens was an indicator of just how senior that official might be.

GCHQ director Robert Hannigan wanted to explain how the agency operated

So the audience - some of whom probably worked for him - cannot have been surprised when Robert Hannigan walked on to the stage.

The GCHQ director - a career civil servant who cut his teeth negotiating with paramilitaries during the Northern Ireland peace process - was frank about his motives in making this rare public appearance.

"Over the past few years we've been talked about by people who are not necessarily our greatest fans", so it was important for a democracy to explain a little more about how the agency operated, he said.

So what did we learn? We heard a robust defence of the agency's methods - in particular its use of bulk data to track terrorist targets identified by MI5 and MI6.

GCHQ is keen to be more open about what happens behind the doors of the agency

All recent counterterrorism operations, including seven attacks frustrated in the UK over the past 18 months, had depended on GCHQ's access to this kind of data, Mr Hannigan said.

No, Edward Snowden had not sparked a global debate about privacy - that had been under way already - but terrorist targets GCHQ had been tracking had learned from his revelations with heavens knows what consequences, he said.

Ben Macintyre pointed to an article, external this week about a leaked document suggesting UK intelligence agencies were sweeping up far more data than they could possibly analyse. Was GCHQ being swamped?

Mr Hannigan would not comment on the article but said it was a fallacy to suggest that "just by having less data you will stumble across the thing you want".

"What you absolutely need to do is to be very ruthless and clever in selecting the data you need," he said.

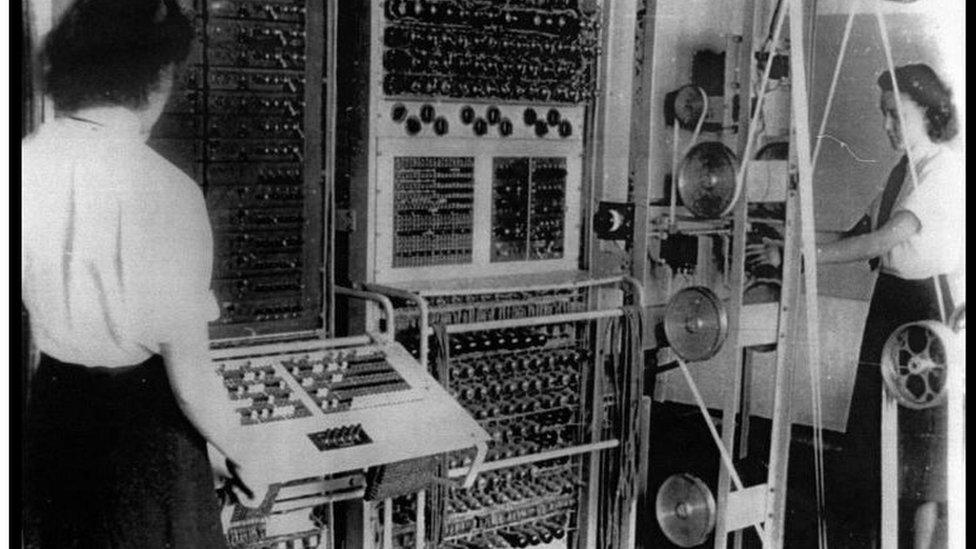

The GCHQ boss referred to the huge amounts of data collected at wartime code-breaking centre Bletchley Park

He reached back into GCHQ's history for an example to reinforce his argument.

At Bletchley Park, the wartime code-breaking centre that had broken the German Enigma system, there had been no way even the very large numbers of staff could look at the huge volume of messages, Mr Hannigan said.

"The clever thing was to work out which messages we needed to put the effort into decrypting," he said.

"So this is not a new problem for us."

And the problem was about to get harder as data went through another explosion with the so-called internet of things.

The GCHQ boss referred to a BBC News report this week about security problems with a wi-fi-enabled car, and said his agency would have to get even better at discarding most of the vast ocean of data that would flow across the world as every object was connected to the internet.

We learned a little about life inside the GCHQ building, which, with its branches of Starbucks and Costa Coffee and pizza for late-working engineers, was made to sound a bit like any tech company.

We were told the agency could not pay as well as Google but offered other satisfactions - climbing a tower in Iraq to fix a communications dish, helping catch terrorists and child abusers.

Could quantum computers unlock the world's encryption systems?

Mr Hannigan negotiated a couple of mildly tricky questions from the audience.

Asked about the threat to its secrets from quantum computing, he said it was some way away but GCHQ was working on that and was a big supporter of strong encryption.

On the EU referendum, he laughed nervously and said the government's position was clear, that we were safer in, but people had to make up their own minds.

It was a deft performance - intriguing nuggets rather than Earth-shattering information handed out by a man who seemed more confident on a public stage than you might expect from someone who spends his working life in the shadows.

But critics of GCHQ will point out that the Investigatory Powers Bill, which they believe gives his and other agencies far too much access to our private data, has made its way through the Commons this week with the support of much of the opposition.

It is an irony that while Mr Hannigan was pulling back the curtain just a little on Britain's spying operations, the politicians who oversee him have changed the rules with barely any public debate.