Death robots: Where next after Dallas?

- Published

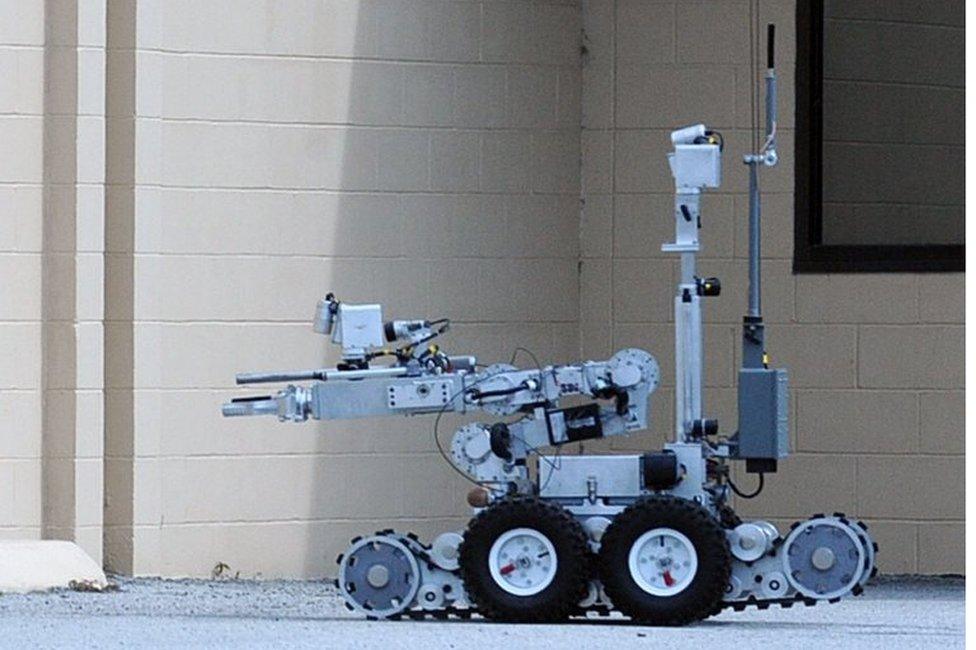

A Remotec Andros F-6A bomb-disposal robot was used to kill the gunman

The use of a robot to deliver an explosive device and kill the Dallas shooting suspect has intensified the debate over a future of "killer robots".

While robots and unmanned systems have been used by the military before, this is the first time the police within the US have used such a technique with lethal intent

"Other options would have exposed our officers to greater danger," the Dallas police chief said.

Robots are spreading fast. What might that mean?

Killer drones

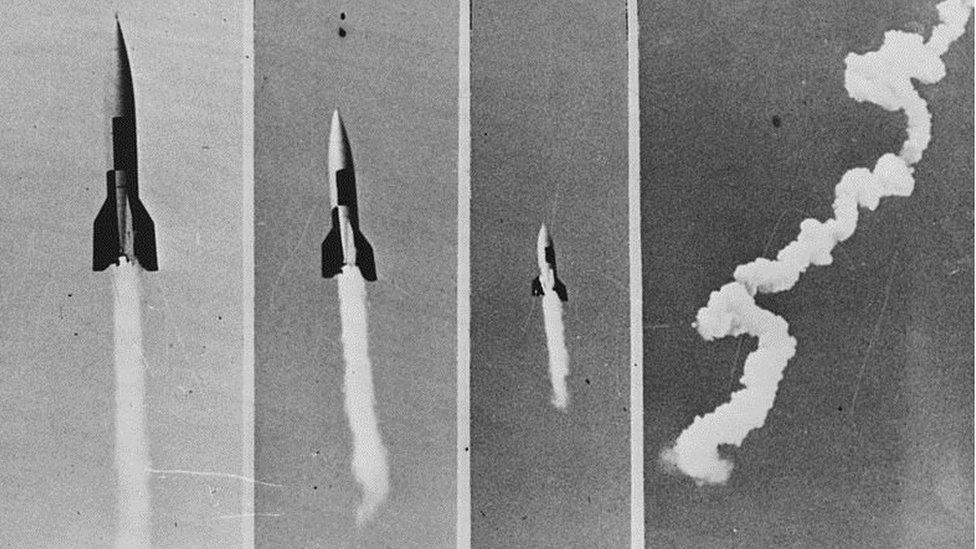

Remote killing is not new in warfare. Technology has always been driven by military application, including allowing killing to be carried out at distance - prior examples might be the introduction of the longbow by the English at Crecy in 1346, then later the Nazi V1 and V2 rockets.

The Nazi's V2 rockets were designed to cause damage to the Allies' cities

More recently, unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) or drones such as the Predator and the Reaper have been used by the US outside of traditional military battlefields.

Since 2009, the official US estimate is that about 2,500 "combatants" have been killed in 473 strikes, along with perhaps more than 100 non-combatants. Critics dispute those figures as being too low.

Back in 2008, I visited the Creech Air Force Base, external in the Nevada desert, where drones are flown from.

During our visit, the British pilots from the RAF deployed their weapons for the first time.

One of the pilots visibly bristled when I asked him if it ever felt like playing a video game - a question that many ask.

Drones are still flown out if the Creech Air Force Base

Supporters of drones argue that they are more effective than manned planes because they can usually loiter longer and ensure they strike the right target.

And, of course, there is the understandable desire to reduce risks to pilots, just as in Dallas the police officers could stay protected.

But critics argue that the lack of risk fundamentally changes the nature of operations since it lowers the threshold for lethal force to be used.

Gun bots

Robots have also been deployed on the ground militarily.

This weapons-grade sentry robot was unveiled in South Korea in 2006

South Korea pioneered using robots to guard the demilitarised zone with North Korea. These are equipped with heat and motion detectors as well as weapons.

The advantage, proponents say, is that the robots do not get tired or fall asleep, unlike human sentries.

When the Korean robot senses a potential threat, it notifies a command centre

Crucially though, it still requires a decision by a human to fire.

South Korea's best-selling automated turret - the Super aEgis II - has a range of some 4km (2.5 miles) - and a machine gun powerful enough to stop a truck

And this gets back to the crucial point about the Dallas robot. It was still under human control.

The real challenge for the future is not so much the remote-controlled nature of weapons but automation - two concepts often wrongly conflated.

Truly autonomous robotic systems would involve no person taking the decision to shoot a weapon or detonate an explosive.

The next step for the Korean robots may be to teach them to tell friend from foe and then fire themselves.

Futurologists imagine swarms of target-seeking nano-bots being unleashed pre-programmed with laws of warfare and rules of engagement.

The US Navy experiments with swarming drones

There are still questions both about how such machines could be programmed to deal with complex situations and the ethical dilemmas involved when you have to choose whether or not to shoot or make calculations over potential civilian casualties.

There's a parallel here with the challenge about what self-driving cars should do when faced with crashing into a group of children or harming their passengers.

The fears over automation are not new.

One of the earliest use of computers was during the Cold War to automate as far as possible the response to a Soviet nuclear attack.

Dawn of cybersecurity

A system called Semi-Automatic Ground Environment (Sage) was designed using networked computers to help spot incoming Soviet planes.

Soon, missiles were also connected up to the systems to shoot the planes down.

One air force captain queried the fact that computers controlled the launch of such missiles and asked if that was dangerous.

Could someone get inside such a computer system and subvert it to send the missiles back into US cities rather than at Soviet bombers?

That question, over whether automated and remote systems could be subverted, led to some of the earliest work on what we now call cybersecurity.

Criminals are likely to be more dubious about robots being used as part of negotiations with police in the future

And there are still risks to remote-controlled as well as fully automated systems.

The military uses encrypted channels to control its ordnance disposal robots, but - as any hacker will tell you - there is almost always a flaw somewhere that a determined opponent can find and exploit.

We have already seen cars being taken control of remotely while people are driving them, and the nightmare of the future might be someone taking control of a robot and sending a weapon in the wrong direction.

The military is at the cutting edge of developing robotics, but domestic policing is also a different context in which greater separation from the community being policed risks compounding problems.

The balance between risks and benefits of robots, remote control and automation remain unclear.

But Dallas suggests that the future may be creeping up on us faster than we can debate it.

- Published12 July 2016

- Published29 July 2015

- Published16 April 2015