Blockchain and benefits - a dangerous mix?

- Published

Some benefit claimants in the UK will soon test a blockchain-powered app

The government has quietly launched a bold experiment using the technology behind the virtual currency Bitcoin - and, if anybody notices, it could prove hugely controversial. That is because the trial involves the payment of benefits and could conceivably involve very sensitive data being made public - or at least that's the concern of some critics.

There is a huge amount of excitement around now about the Blockchain, with endless academic studies and a good deal of investment reinforcing the belief that a permanent ever-expanding and tamper-proof online ledger of transactions must have all sorts of wider applications.

Earlier this year the government's chief scientific advisor Mark Walport wrote a report on blockchain - or distributed ledger technology - which was enthusiastic about its potential to produce "disruptive innovations that could transform the delivery of public and private services and enhance productivity through a wide range of applications." He recommended that the government should back trials of the technology while also looking carefully at the security and privacy implications of using it.

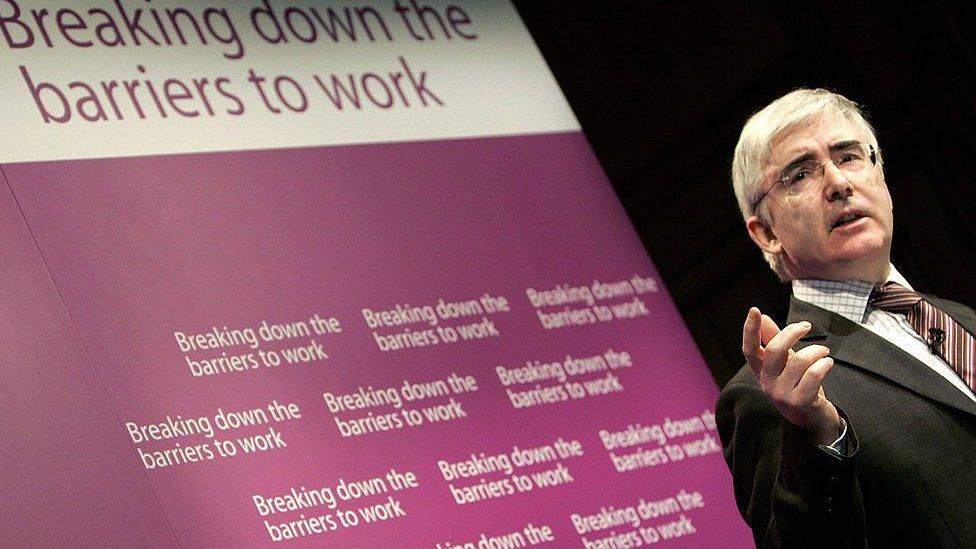

Now, the first real trial is underway, revealed without any fanfare by the welfare minister Lord Freud at a conference last week.

Lord Freud announced the experiment last week

The Department of Work and Pensions tell me it began in May, will run for up to six months, and is designed to look at how the technology might help benefit claimants manage their money. Up to 24 welfare claimants will use an app provided by a company called Govcoin to track their spending.

But this news sounded alarm bells amongst some of those who have been involved in framing the government's technology policies. Their concern is that the payment of benefits is not the right place to start this journey of blockchain exploration.

One recently departed member of the Government Digital Service told me of his amazement that this trial was being allowed to go ahead. His most serious concern was about the privacy implications of putting highly sensitive personal data on a shared ledger "which, by technical design, can never be changed or deleted even if it's inaccurate".

The spending-tracking app is being created by the London-based start-up Govcoin

He also has a theory that the trial - though billed as a way for claimants to manage their money better - could also be "a potentially efficient way for DWP to restrict, audit and control exactly what each benefits payment is actually spent on, without the government being perceived as a big brother".

He sees the possibility that in the future the government could then use the technology to force people to spend benefits on certain things - to make sure, for instance that pensioners spent their winter fuel allowance on their energy bills.

"[That would be a] highly political idea. To hide it behind hyped up blockchain technobabble is not on," he said.

It seems there is also concern in Whitehall about the process by which this trial came to be approved. The chief scientific advisor had wanted a Cabinet Office committee to vet all the various blockchain ideas coming out of different government departments.

It seems that committee has yet to be formed, but another insider has indicated to me that if it had been, the DWP trial would have been quite far down the list for approval.

I put these criticisms to the Department for Work and Pensions.

The government says it will not use the app to keep a record of who spent what

I was told that any data involved in the trial would be handled by the private company running it and personal information would be removed before it reached the department.

"There are no plans to replace any DWP payment systems," a spokesman said.

"This trial is designed to explore how distributed ledger technology could help support financial inclusion and offer budgeting help, and it does not place any restrictions or limits on what a claimant can spend their welfare payments on, nor tracks how they spend them."

There is plenty of enthusiasm for the potential of blockchain to deliver improvements to public services - albeit some time in the quite distant future. But the worry now is that if the first trials go down the wrong path, then public trust in the technology could be irredeemably damaged.