Def Con: Do smart devices mean dumb security?

- Published

Some people now use automatic feeders to make sure their pets get a meal on time

From net-connected sex toys to smart light bulbs you can control via your phone, there's no doubt that the internet of things is here to stay.

More and more people are finding that the devices forming this network of smart stuff can make their lives easier.

But that convenience may come at a high cost - namely security.

Technology explained: What is the internet of things?

Def Con, which sees 15,000 of the world's top hackers gather in Las Vegas, was this year studded with talks about the security shortcomings of IoT gadgets. Holes, data leaks and bugs have been found in everything from CCTV cameras to solar panels, thermostats to door locks. One talk about the bugs in those sex toys revealed that these intimate gadgets are being perhaps too candid with data about the people enjoying them.

And there is starting to be evidence that cyber criminals are waking up to the potential for IoT devices to help them carry out attacks that revolve around bombarding websites with more data than they can handle - a Distributed Denial of Service attack (DDoS).

Home CCTV cameras, domestic routers and other smart devices have all been used for these kinds of attacks.

"Using these devices to DDoS a site makes a lot of sense," said Raimund Genes, European technology head at Trend Micro.

Many cyber criminals who run networks of hijacked machines that can be used to DDoS a site are switching to IoT devices, he said, because they are easier to find, take over and manage than the networks of PCs that are more traditionally used for these types of attack.

Bigger risk

While criminals might abuse in-home devices for attacks, they were unlikely to target individual devices in homes with a view to crashing them or locking them up with malware and demanding a fee to free them.

The economics of those types of attack made no sense for competent cyber thieves, said Mr Genes.

"All of the IoT attacks sound cool but commercial cyber crime doesn't have an interest in them," he said. "They are much more interested in volume because they are running a business."

Osram's Lightify lamps can be controlled by an app

"At the moment they are making much more money from ransomware on Windows PCs," he added.

Deral Heiland, who oversees research into IoT devices for security firm Rapid7, said the broader risks involved with these gadgets became apparent when one considered the ecosystem they were likely to be part of.

"Your mobile phone is part of the loop, so is the app, the cloud interface and then you also have the connectivity between all of these devices," he said. "From a security standpoint, any failing in any one of these devices affects the security of the whole thing, the ecosystem."

Most of the firms that make IoT devices did a poor job of handling updates to their products that fix the bugs security researchers are finding, said Mr Heiland.

However, he said, it was not going to be consumers that felt the true impact of poor IoT security.

Many large firms were now starting to put in place smart systems that manage heating and lighting in buildings, branch offices and factories. Companies could make big cost savings with such systems, said Mr Heiland, giving them a powerful motive to install them.

As these IoT devices are built to work inside offices rather than homes they are typically controlled by more powerful chips, he said. Unfortunately work by Rapid7 suggests they share the same security failings as their smaller counterparts.

This might make them much more attractive to the types of cyber thieves keen to get at corporate networks, said Mr Heiland.

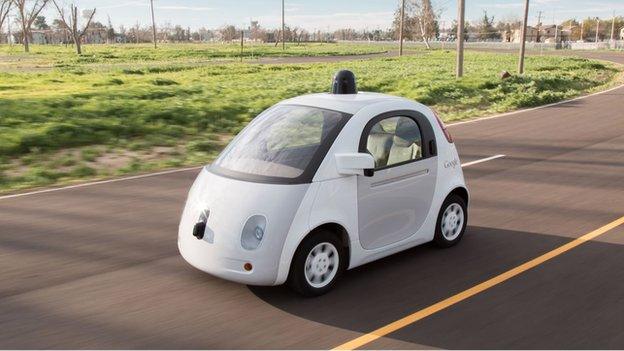

Self-driving cars are the ultimate IoT risk, say security experts

"The person who is doing the administration for the IoT lighting is probably the same person who is doing the administration for the network," he said. "That's certainly someone bad guys want to get to."

Mr Genes from Trend Micro agreed that it was likely the big firms adopting smarter manufacturing systems or putting IoT devices throughout their organisation would feel the brunt of any security failings - not consumers.

"We can see that this might be a problem for industrial services," he said, "and we are working with GE, Hitachi and Siemens on this."

The result could be network-based defences that sanitise data travelling to and from plant and machinery to help it avoid being attacked or compromised, he said.

Rolling robot

One Def Con talk revealed security problems with net-linked solar panels

Cesar Cerrudo, chief technology officer of security firm IOActive, believes security problems emerge because it is usually smaller, newer firms making the gadgets. They were not interested in writing secure code because of the pressure they were under to succeed quickly, he said.

"The problem with the start-ups is that they need to get their product out very fast," he said. "If you put security on it then that slows it down and they spend more money and that makes no sense for them."

This was galling, he said, because the types of bugs being found in the software inside IoT gadgets have long been known about. And, he said, there were well-established methods of writing secure code that avoided these problems.

Adding security after the fact was always more difficult than doing it during design and development, he said.

They also had a duty to realise the threat that smart devices represent - especially when the IoT stuff starts moving around on its own.

"That's when the danger goes kinetic," he said, adding that the ultimate example of an IoT device was probably an autonomous vehicle.

"That's really just a robot rolling down the road," he said.

- Published27 July 2016

- Published28 July 2016

- Published28 July 2016

- Published2 August 2016