Tomorrow's Cities - the future of a good night out

- Published

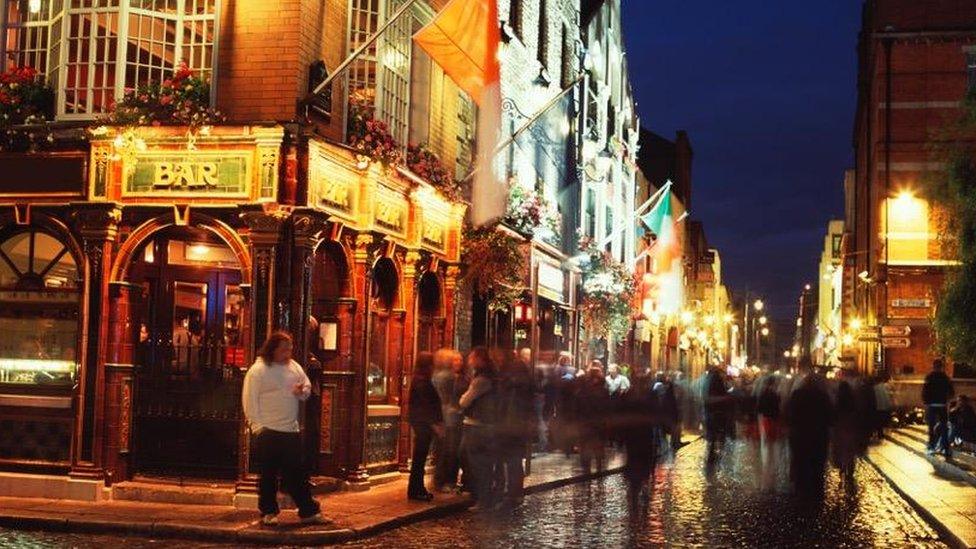

Evenings in cities belong firmly to those who live and work there, and technology can help you find a good night out

Part three of our series A Day in the Life of a City takes a look at how technology is changing entertainment.

It's 18:00, and our day in the smart city is almost over.

The evening rush hour is generally considered to be even worse than the morning one so forget that - it's time to head for a night out.

Let's begin with an app. If you are in London, Paris, New York or Berlin you could make use of CityMapper, which draws on public data to plot the best route between A and B, even offering a rain-safe route.

And there are no shortage of information apps to make sure that you get the best out of your city - from specific city-based ones such as I love Beijing, which offers insights into the best places to go in the city, to Spotted by a Local, which offers tips on the best or cheapest restaurants.

And if you have a specific interest, there are apps for that too, such as Guerrilla Queer, which arranges meet-ups for the LGBT (gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender) community in Boston and New York away from the traditional gay bars.

If you are fed up with the traditional night out at the cinema, virtual reality technology is offering you a chance to feel like you are actually inside a movie.

Virtual reality offers thrill-seekers a chance to star in Ghostbusters

The Void (vision of infinite dimensions) wants to take VR headsets to public spaces and create theme parks around them.

Its first foray is a "Ghostbusters experience" at Madame Tussauds on Times Square, New York.

Visitors enter a series of Ghostbuster-inspired spaces, including a musty old hallway and a lift shaft, surrounded by digital apparitions.

They wear a VR headset, a chest plate that provides haptic feedback and a backpack with a computer in it.

Each virtual object in the space has a real-world counterpart, and visitors take part with up to three others, who appear as avatars next to them.

An artist's impression of how the VR theme park in Salt Lake City will look when it is built

Since it opened in July, it has had more than 50,000 visitors who, apart from complaining about long queues, have given largely positive feedback.

It was, said Void spokeswoman Whitney Thomas, one of the first examples of "hyper-reality" entertainment.

The company had been hoping to start work on a VR theme-park in Salt Lake City in October, but the land earmarked for the project is yet to be built on.

If the Pokemon Go craze taught us anything, it was that the digital and real worlds are going to be increasingly blended together in future entertainment, and there is no better playground than a city.

Increasingly, people can take part in urban games such as Parkman Murders, a smartphone app available in Boston that tells the story of a Victorian murder in the city and invites listeners to take part in the story via a series of location-based experiences.

And last year, visitors to London's financial district could join an interactive theatre piece, Adventure 1, which invited the audience to download MP3s with instructions on how to track a trader (played by an actor) around the City of London.

Increasingly our smartphones are becoming an important social tool, helping us make decisions about where we eat, drink and meet.

We plan much of our lives with a smartphone, but how connected are we to our cities?

Technology can play a huge role in bringing people together, but ironically there is a huge disconnect between our increasingly tech-driven cities and its citizens.

What do you know about your city, for example? Can you see any concrete examples in it of how city-instigated technology is improving your life?

If the answer to this is no, then you are not alone.

According to a recent survey conducted by the Institution of Engineering and Technology, only 18% of people had heard of a smart city, 8% thought it referred to a city with a higher than average proportion of universities and colleges, while 5% thought it was a city with a strict cleaning regime.

Much of that is down to the fact that technology for city authorities is often related to efficiency and making infrastructure and other systems work better.

"Waste management tends not to be high on people's agenda," is how Tom Saunders, author of innovation charity Nesta's report Rethinking Smart Cities from the Ground Up, puts it.

Cities are trying to engage citizens more - offering apps that allow them to report issues such as uncollected rubbish, potholes or abandoned cars.

They are also hosting hackathons for tech-savvy citizens to come up with innovative people-centric tech solutions to a variety of issues.

But for the foreseeable future, the tech agenda of cities and that of citizens is likely to remain poles apart.

Bristol is determined to make technology engaging and fun for citizens

Smart city case study - Bristol

Increasingly, cities are acknowledging that their spaces need to be fun, and no city has embraced this better than Bristol.

Over the years, it has given backing to a series of innovative technology and art schemes, including the annual competition Playable Cities, which calls on artists around the world to come up with novel ways to incorporate technology into cities.

According to Playable Cities producer Hilary O'Shaughnessy, such projects have a valuable role to play.

"Too often smart cities conversations involve white men in suits who are making decisions, but if we want to create multi-faceted cities they have to appeal to everyone," she says.

Previous winner Hello Lamppost - which encouraged members of the public to leave messages on streetlights - has been replicated in other cities around the world, while the 2014 winner Shadowing - which captured a shadow of a person when they passed under a streetlight - attracted 100,000 participants.

Playable Cities is now offering workshops in cities around the world, including Tokyo and Lagos, where it has set up a series of phones on buses to allow people to speak to a stranger on another bus when they are stuck in a traffic jam (traffic jams in Lagos can last for hours).

Playable Cities has a serious point too, says Ms O'Shaughnessy.

"With Shadowing, it started a conversation with people about what we want from the future of lighting in cities and their fears about surveillance," she says.