Google Deepmind: Should patients trust the company with their data?

- Published

The NHS is rich in data and Google is the world's biggest data mining firm

Google's artificial intelligence unit DeepMind is getting serious about healthcare - with ambitious plans to digitise the NHS - but first it needs to convince patients to hand over their medical records.

Back in February, it began work with the Royal Free to create an app to help doctors spot patients who might be at risk of developing kidney disease.

The first most knew of the partnership was when it emerged some months later that it would be accessing 1.6 million patient records as part of the deal.

The records shared by the Royal Free go back over the past five years and include full names

That led to some pretty negative headlines and questions from some of the patients involved as to why they had not been informed their data was being used in this way.

The app - dubbed Streams - is now under investigation by the Information Commissioner's Office (ICO) while the National Data Guardian, which is tasked with safeguarding health data, is also looking at it.

Newly determined to forge a better relationship with the public, Google hosted its first ever patient engagement forum this week at its new headquarters in King's Cross, pledging that it wanted, in future, to work in closer partnership with the public.

"Patients are at the heart of what we do and as we embark on this decade-long opportunity, we really need a diverse group of people to help us design the products," said Mustafa Suleyman, co-founder of DeepMind and head of DeepMind Health.

The audience was polite during the presentation - making encouraging comments and seeming excited about the possibilities.

So far, DeepMind has two other continuing projects:

research into age-related macular degeneration at Moorfields Eye Hospital which will involve the use of one million anonymised patient scans

a new partnership with University College Hospital to see if machine learning can speed up the time it takes to plan radiotherapy for head and neck cancers.

But, during the course of the forum, it became clear that DeepMind has much more ambitious plans when it comes to patient data, so much so that anyone attending could have been forgiven for thinking that it had won a contract to digitise the NHS.

Mr Suleyman spoke at length about a patient portal that would be accessible to both patients and doctors and available on their own smartphones.

It would allow doctors to search a patient's entire medical history in chronological order before they arrived at their bedside. Patients may be able to input their own data, for example, if they suddenly had a change in their condition or experienced problems after an operation.

The plan shocked some audience members who had not spoken out earlier.

"What was astounding to me, was the sense of entitlement that this commercial company clearly feels to access NHS patient medical records without consent and that many in the room seemed to have accepted that unquestioningly," said Jen Persson, a co-ordinator from campaign group Defenddigitalme.

"Patients have been left out so far of what DeepMind has done. The firm is not at the start of 'patient and public engagement' as it put it, but playing catch-up after getting caught getting it wrong," she added.

The patient portal is just an idea at this stage, admitted Mr Suleyman, and his team is probably "years away from building it".

The audience raised concerns about how safe such data would be and valid questions were asked about how DeepMind could ensure data did not get into the wrong hands.

"It may be that we stream data so it is not stored on a local device or that we have Trust-owned devices with an encrypted operating system or that data won't be accessible outside of the Trust's wi-fi," offered Mr Suleyman.

But he admitted there were also big hurdles: "How do patients verify themselves, how do we handle someone forgetting their password? There is a lot of work to do."

There is currently no national agreement between the NHS and DeepMind and the BBC understands that there was no representative from NHS England at the event.

Charity

The forum - which was a mix of formal speeches from doctors and patients who have been involved in DeepMind's trials as well as views from the audience - also heard from a health data-sharing advocate, Graham Silk.

The businessman was diagnosed with leukaemia in 2001 and given three years to live. He found out for himself the power of having his data in the right hands when he was invited to join a trial with an experimental new drug.

He has since set up a charity to put doctors and patients in touch with new drug trials and believes that we have a hypocritical view when it comes to data-sharing.

"Millions go on Amazon every day and give away their name, address, bank account details and it is bizarre that they don't feel the same about health data which has the power to do the most good," he said.

He thinks data is the "lifeblood" of the NHS but cannot understand why some patients might be wary of sharing information that could ultimately save their life or the lives of others.

He wants to see a system where the NHS can earn money from selling patient data to commercial partners.

"Much of the focus of the media and others is on whether using data is safe but, if we are to improve patient outcomes, we have to utilise this precious asset."

Perhaps the most pertinent question posed during the forum was one from a patient who asked simply: "What's in it for Google?"

Mr Suleyman has previously told the BBC: "Ultimately we want to get paid when we deliver concrete clinical benefits. We want to get paid to change the system and improve patient outcomes," something he reiterated at the event.

Ms Persson is not convinced.

"DeepMind couldn't answer clearly what their business model was with these NHS Trusts and what was in it for Google.

"Given that Google spent over £400m buying the DeepMind start-up in 2014, they clearly expect to make money from something," she said.

Google is not the only firm that the NHS shares data with but it is difficult to say how many there are as they are not centrally stored and each trust makes its own agreements.

Each one goes through a rigorous approval process.

DeepMind said that patient information is held "with the highest level of security and encryption.. and isn't shared with Google."

Patients can opt out of sharing data by emailing their NHS Trust's data protection officer.

Only 148 Royal Free patients decided to do so after learning about the DeepMind partnership.

Those figures chime with a survey commissioned by medical research charity the Wellcome Foundation earlier this year to find out more about public attitudes to data sharing.

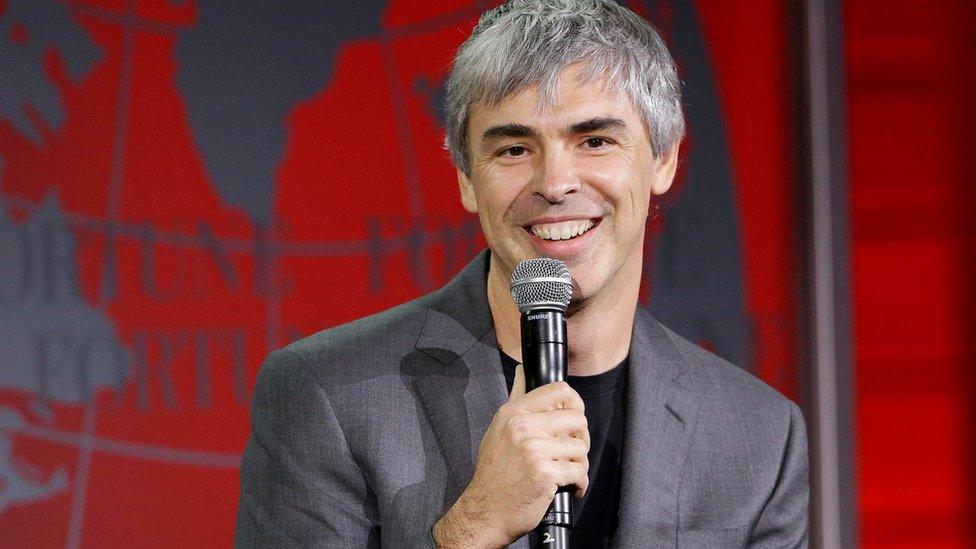

Google co-founder Larry Page, who suffers with a vocal cords problem, has made no secret of the fact he believes everyone should share their health data

Its survey of more than 2,000 patients, conducted in April, found that most were unaware that their data was being shared with commercial organisations and that there were "red lines" that patients felt should never be crossed - such as sharing data with insurance companies.

But only 17% said that they would never consent to their anonymised data being shared with third parties, even for research purposes.

There is obviously a lot of good that can be done with patient data and advances in data mining and artificial intelligence offer an incredible new tool for doctors and care-givers.

But it is a tool that needs to be used carefully, thinks Ms Persson.

"Hospital trusts should think twice before gifting commercial companies confidential data on an ad hoc basis, without informed patient consent, without transparent oversight, and patients should be asking what precisely will it be used for, by whom, and with what safeguards."

- Published31 August 2016

- Published19 July 2016

- Published5 July 2016

- Published8 June 2016

- Published3 May 2016

- Published27 January 2014