The real-world uses for virtual reality

- Published

Think of virtual reality and you will probably conjure up images of fantastical landscapes in a game or film set.

But VR can also be embedded in reality to give people more understanding of the world around them.

Increasingly it is being used as a tool by journalists, teachers, healthcare workers and retailers.

The BBC took a look at a few of the more unexpected uses of the technology.

Autism understood

The film was intended to encourage people to empathise with children with autism

Surveys suggest that while 99% of people have heard of autism, only 16% really understand what it means. In the UK, more than a quarter of autistic people have been asked to leave a public place, such as a restaurant.

In order to address this, the UK's National Autistic Society made a VR film this summer to show people what it was like to live with the condition.

The film takes viewers on a journey with a young, autistic boy as he walks around a shopping centre. They can experience the sensory overload he experiences as he walks around.

Mark Lever, chief executive of the National Autistic Society, says he hopes the film will "help the public understand a little more about autism".

The film, along with Samsung Gear headsets, was taken on tour around UK shopping centres this summer and the charity is also putting together a pack for schools to teach their students about autism.

The film is available via an app and can be viewed on YouTube, external.

Alzheimer's Research UK also released a VR film this summer, intended to put the public in the shoes of someone with dementia.

A Walk Through Dementia, external aimed to show how everyday tasks such as making a cup of tea can be a challenge for someone with the condition.

Virtual meatballs

Fans of the app demanded virtual meatballs that they could cook or throw in the kitchen

Virtual reality is becoming a common tool for people wanting to sell something. Estate agents use it to offer customers virtual walks from potential properties while Westfield shopping centre is using VR headsets to show off the latest fashion collections.

In April, furniture retailer Ikea launched an app that placed users in a fully furnished kitchen. Users could change the colours of the units and walk around the space. The app was available through Steam, using the HTC Vive.

Gamers are, said Ikea's Ingrid Franov, "not a typical Ikea customer" but the retailer was amazed by the reaction.

"In one month we had more downloads than we had expected for the whole six-months trial and people were asking for more kitchen action," she told delegates at the recent VR&AR World Forum in London.

"And what they wanted was meatball," she said.

Meatballs are perhaps the most famous dish in Ikea's restaurants.

When meatballs were added to the kitchen, one user told the firm: "I want you all to know that I have just spent 44 minutes throwing meatballs around a virtual kitchen and I loved every second of it."

"This is really talking to customers," said Ms Franov.

Now the retailer is considering rolling out the VR tool in stores to help customers better envisage how a kitchen design might look.

VR operation

Dr Shafi Ahmed performed VR surgery earlier this year

Healthcare has become one of the big adopters of VR - using it both as teaching aid and to treat phobias.

Surgeon Dr Shafi Ahmed became one of the first to offer a live virtual surgery experience in April 2016 at the Royal London hospital.

Some 5,000 people in 14 countries tuned in to watch the operation to remove a tumour.

Now the start-up he co-founded, Medical Realities, is launching Virtual Surgeon as a product, hoping that such surgery can reduce the cost of training doctors, reach a much wider audience and ultimately "democratise medicine".

Meanwhile, in the US, VR has been used to help soldiers deal with post-traumatic stress disorder and for arachnophobics to overcome their fear of spiders.

In one study, 23 people were encouraged to approach a virtual spider and by the end of the experiment, 83% showed significant improvement in how they could tolerate the situation.

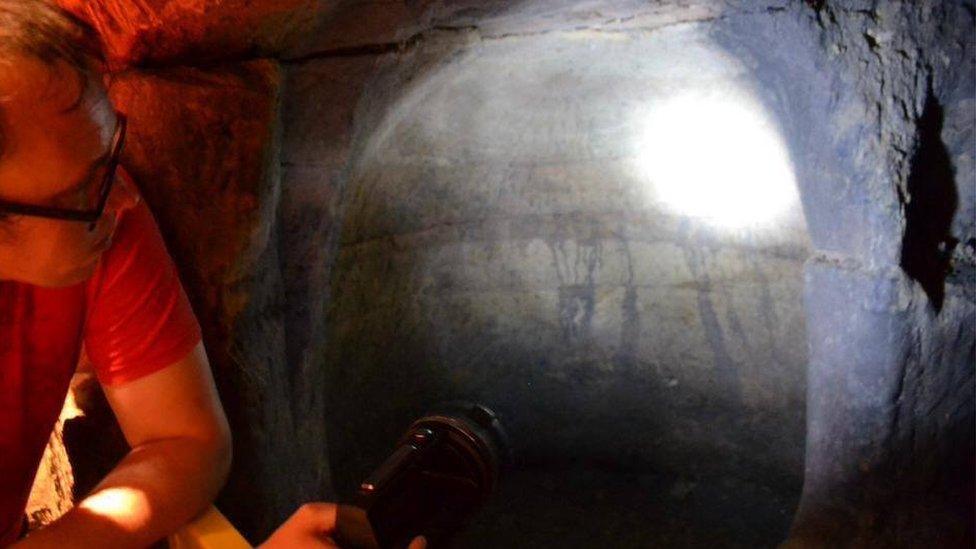

Round the world

There is huge potential for VR in the classroom

In September 2015, Google launched Expeditions, a program designed to take thousands of school children around the world on a virtual trip - from the Great Barrier Reef to Mars.

The kit, which comprises a Google cardboard headset and an app, has just been launched in the UK.

Most pupils have enjoyed the experience although one Year 3 student told the Times Educational Supplement, external that they "were a bit scared of heights so if it could just be on the ground then that would be an improvement for me".

Marcus Storm is the founder of VR start-up Evanescent Studios and he is developing a VR app that he hopes will be used in classrooms to improve language skills. The app is currently being trialled at Imperial College, with Mandarin as a pilot language.

Users can watch Chinese people having conversations and visit Chinese landmarks such as the Great Wall.

Mr Storm is enthusiastic about how VR can transform learning.

"We see a future where kids in history lessons are going back to revolutionary France and interacting with the people there," he said.

It is a view echoed by Nicholas Minter-Green, president of Economist Films.

"It is bringing the joy to education. The biggest challenge has always been to engage and that is where VR can be a very powerful tool," he said.

At VR&AR World Forum in London, he spoke about how Chinese firm NetDragon is testing how VR software and hardware can be used to tell if children are engaged in learning.

"One idea is that headsets could tell when children are tilting their heads, indicating boredom, meaning a change of subject or teaching method is required," he said.

Cash-strapped schools may struggle to afford the hardware or the computing power required for VR to run, and Mr Minter-Green acknowledged that there are many hurdles to overcome before virtual becomes a reality, in school at least.

- Published16 October 2016

- Published6 October 2016

- Published12 October 2016