Children see 'worrying' amount of hate speech online

- Published

- comments

Ofcom suggests UK parents are doing more to protect their children online, but threats remain (stock photo)

One in three internet users between the ages of 12 and 15 say they saw "hate speech" online in the past year, according to Ofcom's latest survey of children's media habits.

It is the first time the UK regulator has posed a question, external about the topic in its annual study.

The NSPCC charity said the finding was "very worrying", adding such posts should not be tolerated.

The report also indicates children are spending more hours a week on the net.

And it suggests that many of the children are too trusting in Google.

More than a quarter of eight-to-15s who used a search engine said that if the US firm listed a link then they believed its contents could be relied on.

Google is second only to the BBC's sites as 12-15s' preferred source of "true and accurate information about things going on in the world"

Ofcom said most of these children had mistakenly assumed that the results were chosen by some kind of authoritative figure who had hand selected accurate pages.

Hateful media

The report was based on interviews carried out with 2,059 families between April and June.

The hate speech question asked: "In the past year, have you seen anything hateful on the internet that has been directed at a particular group of people, based on, for instance, their gender, religion, disability, sexuality or gender identity?"

The children were told this could involve hateful comments, images or videos posted to social media including YouTube.

Of the 12-to-15-year-olds who replied, 27% said they had "sometimes" seen instances of hate speech over the past year, and a further 7% said they had "often" seen examples.

Ofcom noted that children from the three lowest social and economic groups in the UK were twice as likely to have given "often" as their answer as those from more wealthy backgrounds.

"Obviously this is a real concern and like any parent I'd be worried about [hate speech] too," Emily Keaney, Ofcom's head of children's research told the BBC.

"But we also know that children are likely to tell an adult about it - probably a parent or teacher - and that parents are mostly talking to their children about how to stay safe online."

The study indicates parents are becoming more proactive about their children's online safety.

More families said they used home network-level filters to block offensive content than last year. Likewise, more parents said they had changed the settings on their children's devices to prevent them downloading apps when unsupervised.

But one child safety expert said such technical fixes could only go so far.

"We are getting better at filtering out inappropriate content [such as pornography] but speech is considerably more difficult to deal with," said Stephen Balkam founder of the Family Online Safety Institute.

"Parents must talk with their kids and convey their offline real-world values because ultimately it has to come down to the kids' own sense of what is right and wrong.

"One of the things we are trying to encourage is that kids should act on this stuff in a way that empowers them. That can involve telling a site like Facebook or YouTube that they have seen harmful stuff and then witnessing it be removed."

Case study: Sabine and Romilly Bucher, East Lothian

Sabine:

The challenge is to prevent my children becoming obsessed about things they have seen on the internet. If they totally get into a character - a cartoon or real-life person - they can want to see more and more. One clip is never enough. And you never know what they might find if they keep searching for the same thing. The further down the list they go on YouTube the more unsure you are what's there. So, mine always have to ask me before they can press play.

Romilly:

When I'm on the internet I'm only allowed to look up the things mummy says I can look up. That's sensible because she doesn't let me look up silly things that might be inappropriate for me. I like looking at pictures of horses. But I think TV is better than the internet, definitely, because it's bigger and the layout of the internet is not as good.

Rise of vloggers

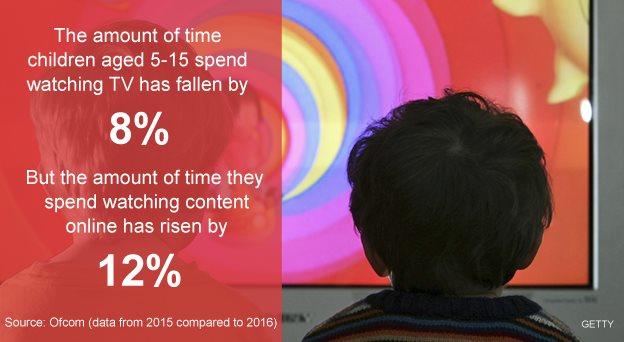

While children are spending more time online, the report suggests they are watching TV less.

For many, YouTube is the most popular destination. But the content they watch differs by age.

Under-sevens say they are most likely to watch TV shows, cartoons and mini-movies on Google's video clip service.

But their older counterparts are more likely to opt for vloggers. More than a third of eight-to-11s and 44% of 12-15s say they watch YouTube stars and other online personalities.

Parents may find it a struggle to keep across which vloggers are suitable, but at least the kids appear to be becoming more savvy. For the first time a majority of 12-15s say they are aware vloggers could have been paid to promote the products they discuss.

Despite all this, it remains the case that the under-12s continue to spend more time in front of the TV than online.

But for the 12-15 group, the study indicates that on average the youngsters spend five hours 24 minutes a week longer online than in front of a TV, with a total of 20 hours six minutes dedicated to online pursuits.

Looking at how the children get online, Ofcom says that more than half of the five-15s now do so via a tablet - making it the most popular type of device.

It also flags that this group is increasingly likely to have been given one of their own.

Mobile phones have also leapfrogged laptops to become the second most popular device for internet use.

The study indicates 32% of the 8-11s now have a smartphone of their own, up from 24% in 2015.

The corresponding figure for 12-15s is 79%, up from 69% a year ago.

This ownership is likely fuelling use of social media late into the evening. Ofcom says 15% of 11-15s are communicating through one of the platforms at 22:00 and 2% are still messaging at midnight.

Facebook remains the most popular social network. But for the first time a majority of 12-15 girls have a Snapchat account.

Group chat facilities gained in popularity over the 12 months since the last study

Ofcom also notes a trend towards increased use of group messaging services within WhatsApp, Facebook Messenger and Instagram.

"Many of these group chats are used for positive activities, like homework groups," says the report.

"But they were also being used in less positive ways, with a fine line between banter and bullying".

- Published15 June 2016

- Published17 December 2015

- Published2 July 2015

- Published25 November 2014