Disturbing the peace: Can America’s quietest town be saved?

- Published

- comments

The BBC's Dave Lee visits the Green Bank Telescope

There's a town in West Virginia where there are tight restrictions on mobile signal, wifi and other parts of what most of us know as simply: modern life. It means Green Bank is a place unlike anywhere else in the world. But that could be set to change.

"Do you ever sit awake at night and wonder, what if?" I asked.

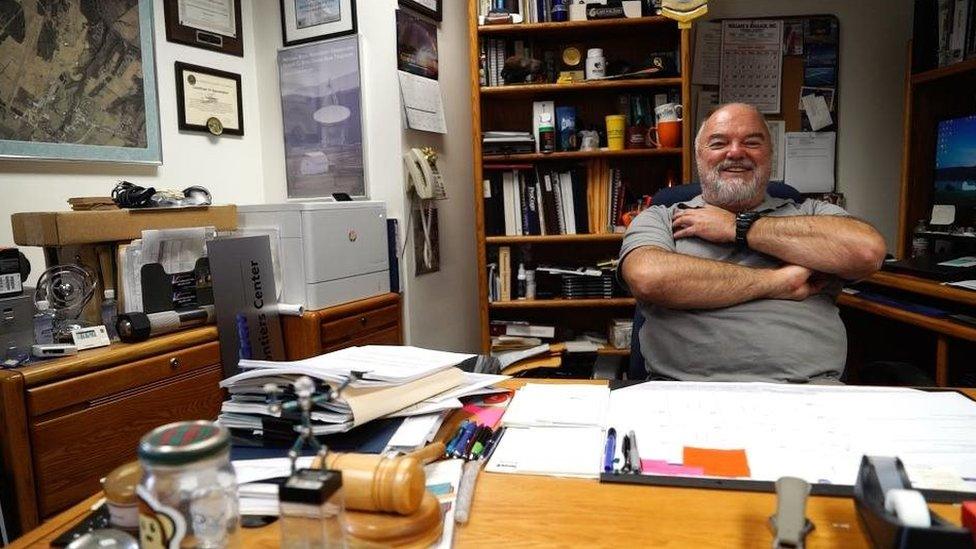

Mike Holstine's eyes twinkled like the stars he had spent his life's work observing.

"The universe is so huge," he began.

"On the off chance we do get that hugely lucky signal, when we look in the right place, at the right frequency. When we get that… can you imagine what that's going to do to humankind?"

WATCH MORE: See the full film on this week's edition of Click

Holstine is business manager at the Green Bank Observatory, the centrepiece of which is the colossal Green Bank Telescope. On a foggy Tuesday morning, I'm standing in the middle of it, looking up, feeling small.

Though the GBT has many research tasks, the one everyone talks about is the search for extra-terrestrial intelligence. The GBT listens out for signs of communication or activity by species that are not from Earth.

And if aliens are aware of our giant ear to the galaxy, there could be no better advert for the beauty of our planet than the town of Green Bank.

Found in beautiful rural West Virginia, the town of 150 or so people is anchored by the GBT. The structure dominates the view over the countryside, but somehow does not seem to spoil it.

Unique people

I am not the first BBC reporter to pop in here. In fact, Green Bank is a source of constant fascination for journalists all over the world. Recently, several people in the town told me, a Japanese crew baffled everyone when it appeared to set up a game show-style challenge in the area.

Outsiders come here for two reasons. One, to marvel at the science. Two, to ogle at the unique people who have chosen to live here.

Green Bank sits at the heart of the National Radio Quiet Zone, a 13,000 square mile (33,669 sq km) area where certain types of transmissions are restricted so as not to create interference to the variety of instruments set up in the hills - as well as the Green Bank Observatory, there is also Sugar Grove, a US intelligence agency outpost.

For those in the immediate vicinity of the GBT, the rules are more strict. Your mobile phone is useless here, you will not get a TV signal and you can't have strong wi-fi - though they admit this is a losing battle. Modern life is winning, gradually. And newer wi-fi standards do not interfere with the same frequencies as before.

But this relative digital isolation has meant that Green Bank has become a haven for those who feel they are quite literally allergic to electronic interference.

The condition is referred to as electromagnetic hypersensitivity disorder. Opinion is split on whether it is real, with the majority of medical opinion erring on the side that it is more psychological than physical.

Dinner with Green Bank resident Diane Schou.

But when I met with Diane Schou, one sufferer, I realised it did not matter whether the condition was "real" or not - for a growing number of people, modern technology has them feeling trapped.

The knock-on effects from the global recession have led to the Green Bank Telescope being on the chopping block.

The National Science Foundation (NSF) is consulting right now on whether they can justify the expense of the telescope. To make things more precarious for Green Bank, other telescopes with similar abilities have been built in other parts of the world, including Chile.

The NSF is not going to just pull the rug from underneath the GBT. As it stands, funding is going to be gradually removed. Not a slow death, but rather a chance for Mr Holstine to court private investment money to keep the telescope operational.

It is working so far - the Breakthrough Listen project, backed with Silicon Valley money, is focused solely on finding other intelligent life. Over 10 years, its investors are planning to spend $100m (£80.3m) on the quest. They are using the GBT as part of an effort to survey the one million stars closest to Earth.

For the locals in Green Bank, the survival of the telescope is not just about seeking ET. It is also the largest employer in the entire county.

The big questions

When I asked Chuck and Heather Niday, who host a weekly show on the charming Allegheny Mountain Radio,, external whether the town would change if restrictions were lifted, they were reserved.

Sure, the kids would love access to Snapchat. But the fabric of the town would not be affected. It is a rural community and no amount of mobile phone signal will change the nature of this tight-knit town.

If like me you find it unfathomable that we are alone in the universe, then Green Bank is an utterly essential utility. When I asked Mr Holstine to justify the money the US government spends on the facility, he dug deep.

"How many of us have walked out into the night and looked up at the stars and stood there in wonder?

"We don't produce widgets. We don't produce something that you go to the store and buy. But we do produce education. We do produce research. We do produce answers to questions we haven't even asked ourselves yet.

"Those questions are the basis of what it means for us to be human. That constant search is done right here every day."

Follow Dave Lee on Twitter @DaveLeeBBC, external and on Facebook, external.