Tech Tent: Is technology good for us?

- Published

Stream the latest Tech Tent episode on the BBC website

Download, external the latest episode as a podcast

Listen to previous episodes on the BBC website

Listen live every Friday at 15.00 GMT on the BBC World Service

On Tech Tent this week we ask whether the tech industry is out of touch with the real world.

In the rush to disrupt every industry and to reinvent the way we live, do the tech utopians forget the negative impact some of their miraculous products can have on the lives and jobs of many people?

The Amazon Go store has done away with staff on the tills

Shop smart

This week Amazon unveiled an idea for stores without checkouts or cashiers - and while it had the tech world swooning, others were aghast. They were not convinced that the wiping out of millions of retail jobs along with another area of human interaction was progress.

It seemed to reinforce the idea expressed by the noted technology thinker Om Malik in a recent New Yorker article, that Silicon Valley has an empathy vacuum, external. We've been speaking to Om who tells us that the Amazon Go concept is an example of the kind of technology that is now being invented without much thought - "the speed with which change is happening is far ahead of our capabilities as human beings to deal with it".

He thinks Silicon Valley needs to be rather more reflective about the impact its innovations are having on people who are fearful about the future - and he links this general anxiety about technology to the UK's Brexit vote and the rise of Donald Trump.

We've heard a lot on Tech Tent about a future where jobs are threatened by automation and artificial intelligence - but we assumed that was a distant threat. Suddenly it seems to be a very present worry for millions of people.

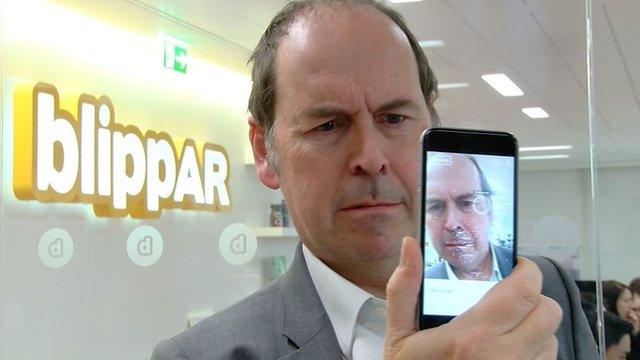

The app already has public figures logged in its database

Facial recognition - fun or furtive?

Have you ever come across someone whose face you recognised but you couldn't remember their names? It's always happening to me.

Now - as I reported earlier this week - there's an app for that. The augmented reality company Blippar already allows you to scan objects with your smartphone's camera to find out more about them - now you will be able to scan faces too.

But facial recognition software can be controversial - and this could be another of those innovations which sound great in a company brainstorming session but have unintended consequences in the real world. We hear from Blippar's co-founder Omar Tayeb who tells us how the app works - and why we shouldn't be worried about its implications for privacy.

Social media firms are searching for ways to fix the problem of fake news

Fake news - the search for solutions

Our final story is about another area where the tech industry's reputation is coming into question - the proliferation of fake news stories spread over social networks and via Google searches.

The tech firms are now starting to respond with initiatives that could help readers understand what is true and what is not - but what can the traditional media firms do?

Our reporter Jane Wakefield has been along to a hackathon where media organisations tried to work out what they could do to regain the trust of their audiences - and to show them that truth still matters:.

We hear from the Guardian, the UK's Mirror newspaper and Santa Clara University's Markkula Center for Applied Ethics about how hard it is becoming in the online world to distinguish between news and propaganda. Ann Gripper from the Mirror argues that the problem now is that social media users get rewarded for sharing stories - fake or not.

Critics of the mainstream media will argue with some justification that the problem started long before many people got their news online. So whose job is it now to decide what is true - and put clear markings on fake stories? You might think that was the function of editors - but Alex Sander of the Guardian tells us "it's the reader's job to mark things as fake".