CES 2017: Has tech's sensor obsession gone too far?

- Published

Sensors are everywhere - even in the shower, showing how much water is being used

The Consumer Electronics Show gives insights into all sorts of problems you never knew you had.

How do I manage to go to sleep at night without knowing my bed is monitoring my heart rate? Why don't my home speakers levitate? How did I survive childbirth - twice - without an app to time my contractions?

My alarm clock is not smart enough to remind me to pack the kids' PE kits on a Tuesday, and my shower doesn't light up if I'm using too much water.

The show hasn't even started yet and already I feel in need of therapy.

I have just returned from CES Unveiled - a bustling curtain raiser before the enormous trade fair itself begins.

I spent three hours roaming the stands, watching demonstrations of endless gadgets far smarter than me, avoiding a dance with a robot that was quite obviously a person in a costume, and trying to work out when this became my actual life.

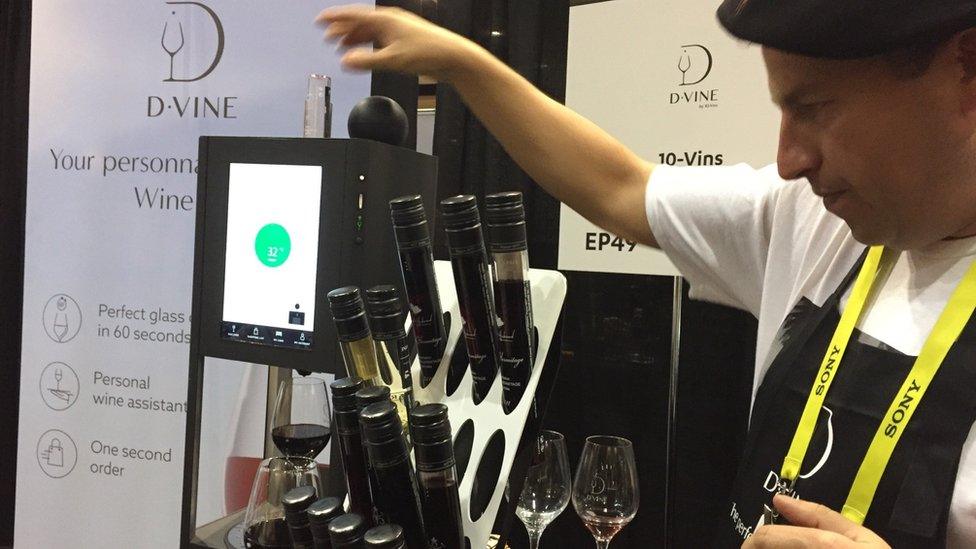

Can tech create the perfect glass of wine?

Fortunately, smart wine dispenser D-vine, by French company 10-vins, was on hand to pour me the perfect glass of wine, at the perfect temperature, to match the food type I selected on the app as my imaginary dinner.

A kind of virtual sommelier approach, rather than the let's-just-grab-that-bottle-standing-next-to-the-cooker approach favoured by many humans I know.

The wine it selected sounded amazing.

And it even even came in a precisely measured glass-sized test tube - although I was sad not to be treated to an extra slurp. AI doesn't understand extra slurps. Yet.

There was a whole area dedicated to smart homes - from doorbells to light bulbs, security devices to voice-activated digital assistants.

They are not the most exciting of objects in themselves but the sector is thriving, says Steve Koenig, senior director of market research at the Consumer Technology Association (CTA), which organises the event.

Levitating speaker anyone?

"Connectivity will be the major focus of CES 2017," he tells me.

"Our research has shown that once consumers adopt one of these [smart home] products - like a connected thermostat or a smart lock - they are very much more likely to adopt the second, third or even fourth product, because they see the convenience."

At a table full of brightly coloured robots I met Robin Raskin, founder of a company called Living in Digital Times.

"Everything you ever imagined is talking to the internet," she says.

Robin is right about that. Smart hairbrushes, dog collars, pet feeders, beds, even the tea bags. Everything in that room felt like it wanted to communicate, to connect, to monitor what you're doing and then use that data to improve your life - whether it's your relationship with your pet or your ability to make a decent cuppa.

CES logo

Crowdfunder Jagger and Lewis was demoing a fitness tracker for dogs, endearingly modelled by an ever-patient hound called Piper The Wonder Dog.

With the help of inbuilt sensors including an accelerometer and a compass, it can supposedly tell you when your dog is hungry, thirsty or why it is behaving in a certain way, according to communications manager Justine Jungelson - although she wasn't really able to explain how.

The device will eventually retail for $200 (£165) and should ship in April, she tells me. I don't have a dog but I thought that sounded quite expensive.

"When you love your dogs you spend a lot of money," she replies.

And that is probably how we've ended up with a Fitbit for dogs.

Surely every parent needs a cuddly sheep that is tracking their child's sleep pattern?

It's not just our pets that are being urged to enjoy the benefits of sensors - a lady called Meghan wearing a pair of purple pyjamas introduced me to Dozer, a sleep tracker for children, disguised as a cuddly sheep.

"He plays music to help your child sleep, he detects movement, he can tell how well the child slept, he can correlate what music was playing while the child slept so over time he can curate playlists for how the child slept," she says.

Do dogs need fitness monitors?

It sounds like a great idea, but does it feel a bit intrusive to be tracking somebody else's sleep and manipulating it in that way - even if it is your own child?

It's not surprising that some experts are sceptical about whether the tech industry's current obsession with sensors is echoed by consumers.

"Just because you can monitor an activity doesn't mean you should," tech analyst Caroline Milanesi says.

"A lot of times we see products that are trying to solve a problem that just isn't there."

- Published4 January 2017

- Published4 January 2017